Edition 82

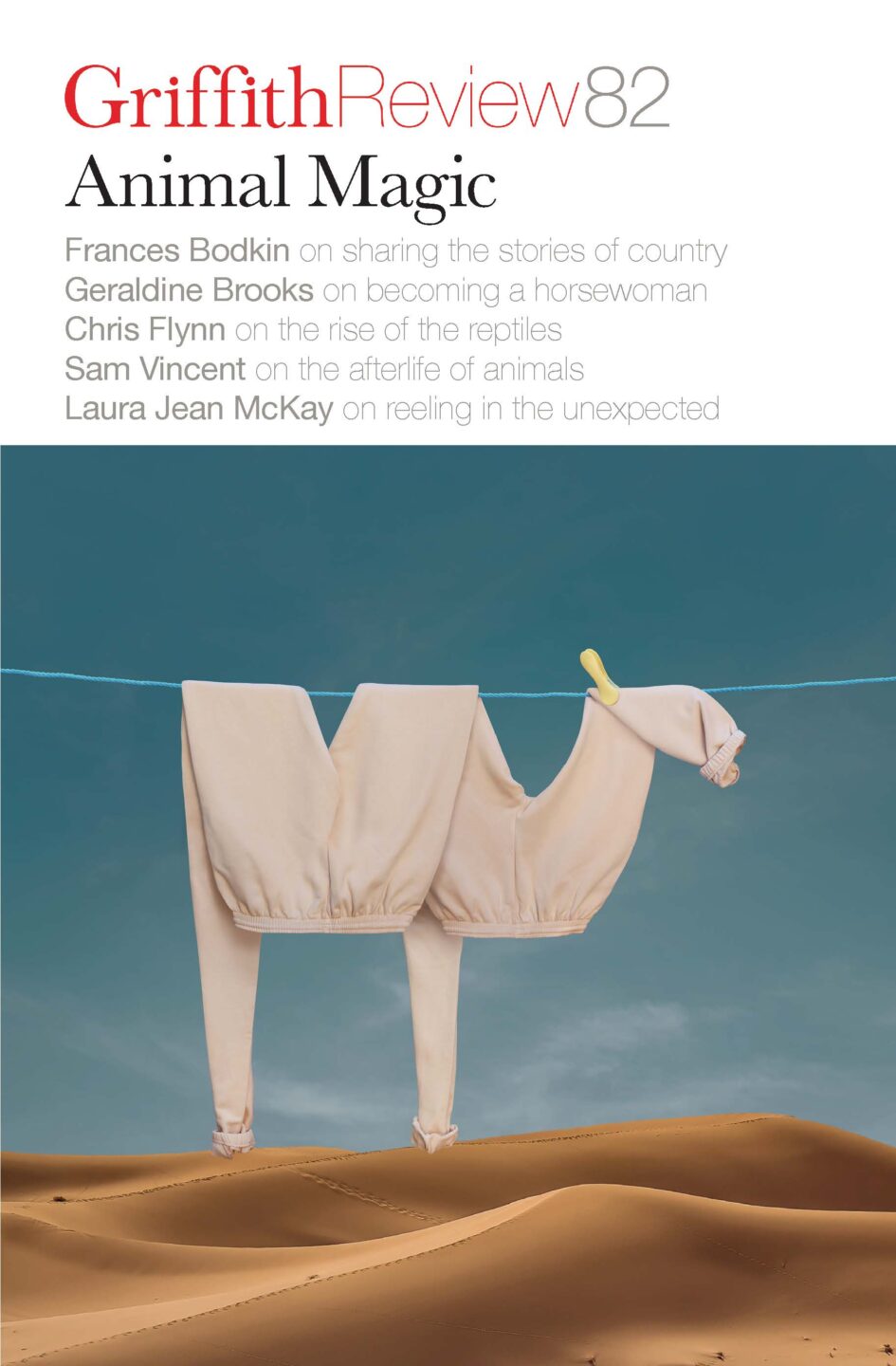

Animal Magic

- Published 7th November, 2023

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-89-4

- Extent: 207pp

- Paperback, ePub, PDF, Kindle compatible

Whether it’s man’s best friend or the king of the jungle, animals occupy a central place in our social, emotional and cultural lives.

With pieces from Chris Flynn, Geraldine Brooks, Laura Jean McKay and many more, this edition of Griffith Review visits habitats near and far, wild and domestic.

We visit the site of T-rex excavations, swim with turtles, spend a night at the zoo, find out about the storied history of mould, and diagnose pre-teen horse girls.

We consider the lobster – and dodos, cockatoos, elephants, tigers and more. There’s even a lone – very loved – soft-toy rabbit tucked away in our pages.

The cat’s out of the bag: Griffith Review 82: Animal Magic will bring the wonder of the animal world into your hands.

In this Edition

Dog people

We’re social animals, humans – from the wiring of our brains to the shape of our societies. If recent pandemic lockdowns taught us one thing, it’s that we need to be physically close to each other, to socialise not just as avatars or gigabits but as live, warm, fallible bodies. Our dogs knew this ages ago.

The tiger and the unicorn

Tigers are as concrete a metaphor as any man could wish: ferocious, territorial loners requiring vast landscape and huge quantities of prey. Henry had named his firm in the spirit of the money making he set out to do: an apex hedge fund, stalking longs and pouncing on shorts, untethered to the groupthink of a pack.

Rise of the reptiles

In tandem with these plans to cultivate meat in laboratories, bioscience companies in Europe, North America, South Korea and China are currently working to resurrect living, breathing examples of the woolly mammoth, thylacine and dodo. While this may seem foolhardy, the intention is to restore nature’s balance by rewilding animal habitats and damaged ecosystems. Science will also provide a means to preserve species on the verge of extinction while weaning humanity from the environmentally damaging practices of commercial livestock farming…

Into the void

I think with a little fear, as I often do, of the many other (and much larger) creatures whose natural territory this is, and scan the surrounding water for any dark, fast-moving shadows. But soon I relax and settle into the rhythm of my freestyle stroke. Breathe. Pull. Pull. Pull. Breathe. Pull. Pull. Pull. Breathe.

The rabbit real

I know you want to ask me if I had a difficult childhood, if I suffered physically or mentally in any way that might swerve from the ‘normal’ pattern of development. But I have nothing to report: no tales of abuse to exploit through memoir; no scars to split open for internal poking. I had friends when I wanted them but was also happy when alone with the rabbit. I was never spoiled with possessions, and my parents were playfully involved in the amusement of my sister and me (we were one of those daggy families who made short films about ghost houses and played charades by candlelight during blackouts). There’s no angry revelation (I don’t think) buried in my early years. All my fears, anxieties and self-loathing seem to have developed later in life, by which time I was already rabbit dependent. Of course, the assumption that such a deep attachment develops as the result of a troubled childhood is perhaps misguided, overlooking the fact that even an ‘ordinary’ childhood carries its legitimate stressors.

Object permanence

Tigger arrived with one eye and a tender but wary disposition, and at first it seemed like the missing eye would be the locus of his mystery. But within a few months of his living in my small apartment, he began presenting strange troubles – back legs listing when he turned a corner, spasms in his resting spine – that were quickly diagnosed as arthritis and diabetes.

We so often use the phrase ‘the stiffening of joints’ that we forget it’s a courtly term for the elision of matter, without which the bones rub together, scrape and grate. While I acclimated to managing the diabetes – an injection every twelve hours, which Tigger didn’t mind, quickly learning to associate it with freeze-dried chicken snacks – he also started hesitating before jumping on and off surfaces, before finally doing so despite the promise of pain.

When the birds scream

I read books in which girls like me made friends with cockatoos and galahs, and my mum told me stories about my pop in Queensland who could teach any bird to speak and to whistle his favourite country songs. My favourite story was the one about the bird who used to sit on his shoulder while he drove trucks for work. I wanted a bird that would sit on my shoulder, and I thought that because I had a pop who talked to birds, I could too.

ut back then I didn’t realise the difference between teaching birds to speak with human voices and having birds speak to you with their own voices. It was a lesson I didn’t learn until Pop sent me Normie.

As dead as

As a Mauritian person, I’ve always known about dodos. I first heard about them from my dad’s family. The dodo was only ever found in Mauritius, and I naively believed that everyone knew that. But when I was relaying my experience of listening to the podcast to a group of friends, they were surprised to hear that the dodo was Mauritian. They are not the only ones. Since that conversation, I’ve been playing ‘where does the dodo come from?’ for months. Not many people know, and I’ve been angered by this, not at my friends but at the way in which stories of the dodo seemingly exist outside of place and time, when to me place and time are integral to my understanding of the dodo.

The animal in the walls

Scrambling the scientific assumptions of the time, fungi and fungi-like organisms also gained new cultural and symbolic meanings. They began to sprout in the claustrophobic houses of gothic fiction and the swamps of horror; in the centre of the Earth and on the distant moons of science fiction; in utopian tracts, revolutionary and anti-revolutionary literature; and in the parasitic infections of the post-apocalyptic. Fungi were metaphors that fruited in many genres, mirroring human preoccupations with communal life and our tangled place in ecologies and economies. Creeping, co-operating, intertwining, fungi continue to feed our cultural dreaming and political unconscious.

Taking the reins

THE PHENOMENON OF the horse girl is widely ridiculed and poorly understood. The stereotype is the butt of many jokes on social media: everyone seems to have met a horse girl, though few will admit to being one. But derision, containing as it does a buried core of anger, raises questions. What exactly do we find so irritating about this particular obsession? And for that matter, why does the phenomenon take the form it does? Why horses? Why girls?

The defining characteristic of the horse girl is being ‘horse mad’: having a fanatical interest in horses. Other common traits include social awkwardness, more affinity with animals than people, and a tendency to indulge in daydreaming and make-believe games past when most peers have moved on to more ‘teenage’ pursuits. There’s an invitation here to consider neurodivergence, and I wonder if my difficulty in social interactions as a child might have been a precipitating factor in becoming a horse girl.

Sartre’s lobsters

In The Secret Life of Lobsters (2004), Trevor Corson describes how, before the lobster’s status had sufficiently improved for affluent urbanites to desire its meat, ‘lobster’ was used derogatorily to describe British redcoats during the American Revolution and, later, dupes or fools in general.

Divine dis/connection

MY FAMILY HAVE always been wary around animals, especially in the home (I could have written ‘non-human animals’, but a stark separation of human from animal is truer to them). My brother and I have changed because of animal encounters in share houses and via intimate others, and we now each live with a partner who likes cats (I ‘have’ one cat; he ‘has’ two). But our parents have remained the same.

Where the wild things aren’t

Melbourne Zoo knows that it sits in an uneasy position as a conservationist advocate, still keeping animals in cages, and with an exploitative and cruel past. Our guides for the evening walked a practised line between acknowledging the zoo’s harmful history and championing its animal welfare programs, from the native endangered species they’re saving to their Marine Response Unit, a dedicated seaside taskforce just waiting for their sentimental action movie. ‘We’re here to look after animals who we’ve decided are not going extinct,’ one guide said grimly, jaw clenched, auditioning for a lead role. ‘Not on our watch.

Talking to turtles

Eighteen years ago, I moved to a seaside village on Cape Cod on the north-eastern shore of the United States. Finding the ocean there too dangerous, I swam in ponds. I waded through mud the consistency of yoghurt ever on the lookout for fifty- and sixty-pound snapping turtles. I dove in, swam and got out as fast as possible.

Smoking hot bodies

Since 2013, South Korea has mandated the use of compost bins for uneaten food and the country now recycles an estimated 95 per cent of its food waste. Similar schemes exist in Europe and North America, and in June, Nevada became the seventh American state – after Washington, Colorado, Oregon, Vermont, California and New York – to legalise human composting.

Known as ‘terramation’ or ‘natural organic reduction’, the process entails a certified undertaker placing the cadaver beneath woodchips, lucerne and straw in a reusable box, where, with the controlled addition of heat and oxygen, it decomposes within eight weeks. Anything inorganic (hip replacements, pacemakers) is then removed, and remaining bone and teeth fragments ground down and added to the mix. The deceased’s loved ones can spread the compost as they choose, with no need for concrete burial vaults and steel caskets, or the energy required for cremation.

Unlike the usual resistance to decarbonisation from those in the business of polluting, opposition to terramation has come from an unexpected source: Catholicism. The Catholic Conference – which represents the Church’s bishops – in each US state where the practice is legal has denounced it as an attack on the dignity of the body and a threat to its eventual reunification with the soul…

Fly on the wall

Animals are extremely important and extremely neglected in our public discourse. We’re not even paying enough attention to human rights and human justice issues, and we’re paying next to no attention to non-human rights and non-human justice issues. That doesn’t mean that we don’t care – people do care about animals, and they want animals to have good lives – but we’re either unaware of or unwilling to acknowledge all the pain and suffering that animals experience as a result of human activity.

Narratives of the natural world

All kinds of interpretation are a form of fiction. These are fictions that we need in order to connect with the larger environment. When our current thinking has failed to make us think of ways to connect with the environment, art may be the only way we can have access to new ways to think about where we are in relation to the environment.

A life with horses

In 2011, I was invited to a writers’ retreat in Santa Fe. It was held on a lovely old ranch with beautiful horses – Western Paints, Appaloosas – and one of the wranglers noticed me admiring them and invited me on a trail ride. It was an ecstatic experience.

Easy rider

My first bull-riding job was a portrait of a young rider named Ian ‘Irish’ Molan from Cork, Ireland, for the upcoming event in Darwin that weekend. I attended the event that weekend and photographed behind the scenes and focused on Ian Molan in action. When it was the Irishman’s turn, he was thrown off the bull, who stomped on the rider’s chest repeatedly. I thought Ian was going to die. The bull was relentless.

Seeding knowledge

There’s so much we can learn from the plants, even the little annual plants, and we don’t take notice of them. Gymea lily flowers can tell you when the whales are coming. One of the things I’ve investigated is why the ants can tell the weather – I carried out an experiment when I was at Macquarie University, and what I found was that if the groundwater level rises, you can expect rain, and the ants will pick this up.

Fish

He hasn’t caught one in twelve years or more, not since just before Ritchie – Hayley’s oldest – was born. The deboning alone can take half a morning and you have to strip that tail to its cartilage very carefully because there’s a layer of green resin, bitter. In small doses it ruins the meat; poisonous if you eat too much.

Mother of pearls

But we are more animal now than we’ve ever been. We read the water that leaps into our pools; we filter all kingdoms of life through our gills. We understand that the tendrils connecting one life form to another run much longer and deeper than you might expect. And we can entertain the notion that our strange tasks were like the fateful beats of a butterfly’s wings, and maybe the witch was a rare genius, able to perceive how the purloined dog, the pawned bird or the swapped cats would, in the mysterious rippling of the universe, lead to our deepest desires coming to pass.

Before I forget again

I am a ceramic horse in kintsugi fields. Shards shred my tongue to gold rivers. Cracked and crazed – from fire gallops beast. Memory slips lapis lazuli. I break curses, gather spells. Nudge fresh letters in water troughs – watch words bob – shiny new apples to crunch.

A perfectly ordinary dachshund observes the problem of being

Breathing your small inauspicious body almost into incomprehension, supine and crouched, lost to the world, or to that portion only dachshund speech describes, your propulsive unyielding deeds underwritten now by everyone who threatens our front door. (I suspect they are all terrified. Perhaps we have lost visitors.) I know, some...

Help wanted

The opening said no training required; the slaughterer’s tasks are two: stun and slaughter. With a third parenthetical: Remove the organs and the waste as needed. Heifers all have name tags here: Venus, Paloma, Anna, Summer, they trudge through brown grass, blackberries, come up to the fence in the evenings, eat the rose petals, birch saplings kneeling into...

Anemone

Lady, in this heavy light you show tender: waving your insides outside, buffeted by the sea’s old heave ho. Nobody calls out medusa – but there’s a distinct resemblance about the tentacles. The currents drag in silver mercies. Your face flares and ripples. Look, it was never meant to be easy: day...

metanoia

the book holds the horse – rustling in there, taking pages between lips, rubbing upper lip across them, nostrils twin jets of air as it seeks sweetness maybe it will kick apart the pages, toss them into an array, turn a circle and roll in this dry bedding, maybe it...

felix and jango

two black cats patrol our street felix and jango I can’t tell them apart when I see one of them walking past I say, ‘hey felix or jango’ they don’t bother to look at me they know I’m a dog person and they know I know they know felix comes from up...

A new animal

My son has made friends with the daddy-long-legs under the kitchen bench. Each morning I am freshly summoned to ‘um ook at em.’ Come look at him. The body: a dot of graphite huddled in the corner, its pencil-line legs all bent up in a scribble. I am relieved he is not like me as a child:...