Welcome to GR Online, a series of short-form articles that take aim at the moving target of contemporary culture as it’s whisked along the guide rails of innovations in digital media, globalisation and late-stage capitalism.

The years happen again and again

A work of autofiction, A Girl’s Story has two protagonists: Annie Duchesne, an innocent seventeen-year-old camp counsellor, and Annie Ernaux, an experienced woman in her seventies.

Social media’s swan song?

Social media is now so bad that when parents sue TikTok for the role they believe it played in their children’s deaths, it feels terrifyingly quotidian. These platforms are ruining our health, the planet and our diplomatic processes.

The fair-go fallacy

Running as an independent parliamentary candidate is like building a plane while flying it – there’s no party machine, no head office, no ready-made team. Everything rests on your shoulders, and more often than not, it comes down to one thing: money.

Working body

We are taught to fear visible improvement. We are taught, passively and explicitly, to be ashamed. It is bad to look strong and muscular: our figures should not have a noticeable presence; they should not occupy too much space.

wet flowers

names: zoloft. lyrica. cipramil. avanza. neulactil. quetiapine. cymbalta. because. because of it. depression. major depression. dysthymia. melancholia. intractable. medication-resistant. they’re called clamshells, those little plastic cavities. yet they never yield a pearl.

Certified flesh

To put it simply: the raw fascination with our own physicality – our bodily processes – is now a general cultural phenomenon. Reality is catching up to body horror, as human beings become uncanny to themselves.

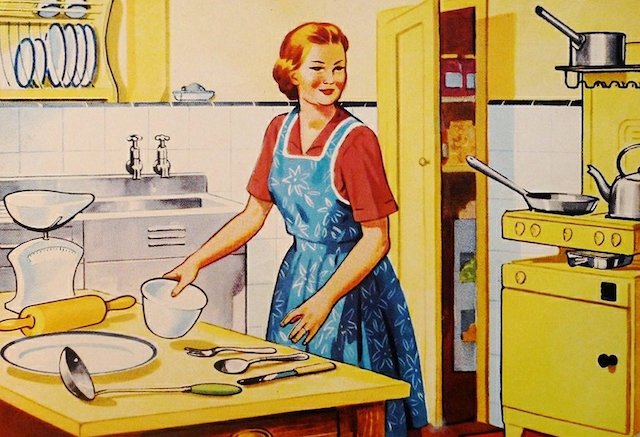

Working from home

Not surprisingly, the tradwife movement has been broadly criticised for its conservative sentiments. I agree with these assessments... But much of the discussion in response to the trend also, I think, tends to miss the point. Because if we look closely, we can see that the central concerns of the tradwife movement are indeed feminist concerns.

Fire and finitude

Nobody any more seriously doubts that cigarettes are injurious… What is not well understood by those opposed to smoking is that the danger of cigarettes is not antithetical or even peripheral to their appeal – it is central to it.

Bill’s secrets

Janet was about to discover that Bill was born into a Welsh coal-mining family, most of whom were still alive when she married him – including his mother, living in the Probert family house in Ynyshir. Ynyshir, we learn, is in the Rhondda Fach, South Wales. Apparently Roy simply disappeared from their life at the end of the Second World War.

Notes from a Sunshine City

I feel like our collective relationships with The House™ as a motif changed so much during that time; the housing crisis, lockdown and climate apocalypse were looming large all at once. Personally, I developed this kind of bizarre voyeuristic relationship with the suburbs and houses I passed on my mandated mental-health walks.

Post-apocalyptic parenting

How does one balance raising children with a sense of wonder and innocence in a world that’s just waiting for them to get hot/legal/sign up to the heterodoxy? As their mother I reserve the right to irrevocably damage them. It’s my job to give them some good therapy fodder in case future them have any money to spare after buying future air and water.

Beyond Bluey

What I want to explore instead is a recurring question for Australian producers who are trying to ensure that Australian stories – like Bluey, like Fisk, like Colin – continue to be made. And that question is… What are we good at?