Edition 83

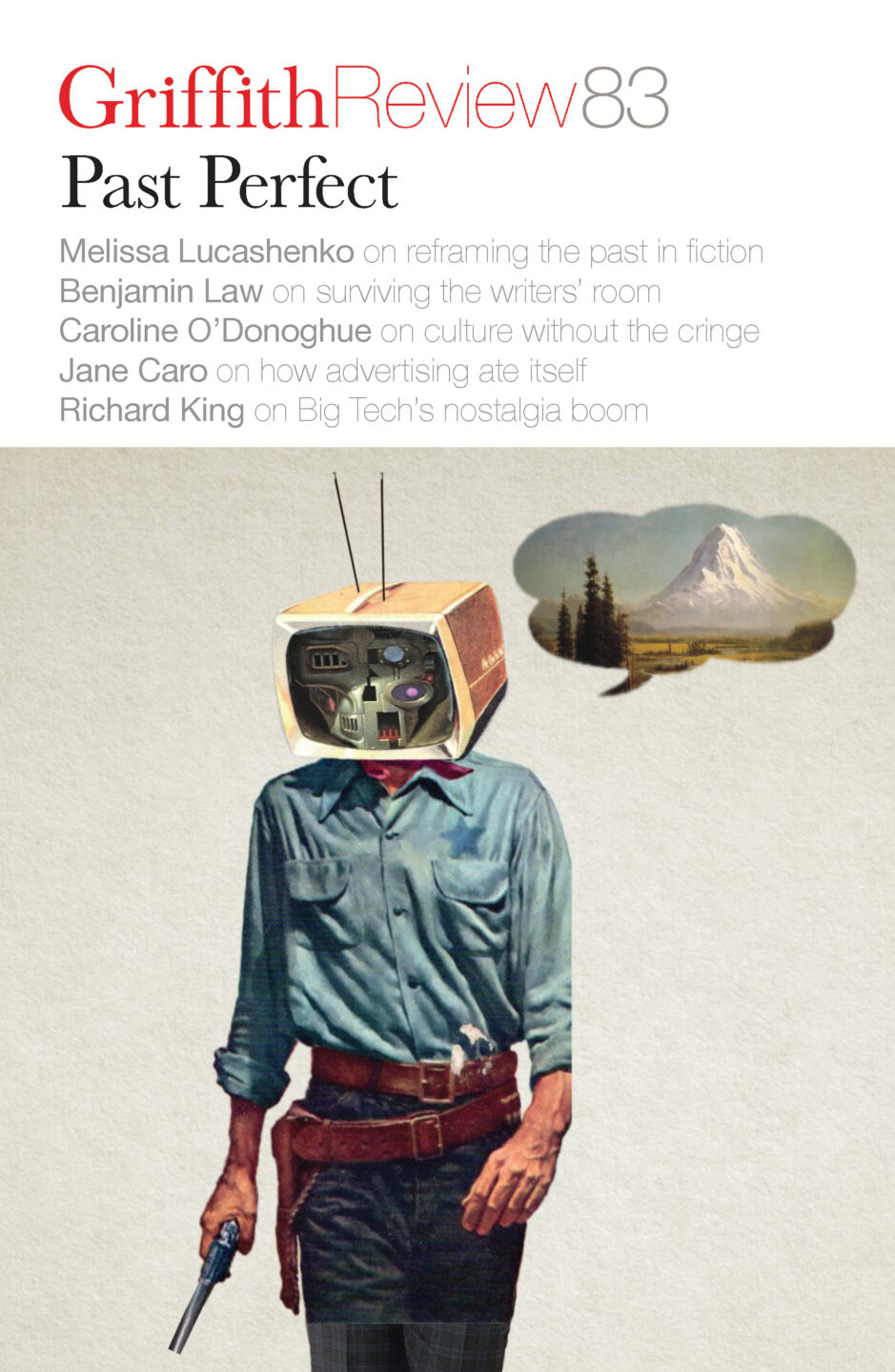

Past Perfect

- Published 6th February, 2024

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-92-4

- Extent: 203pp

- Paperback, ePub, PDF, Kindle compatible

The past, famously, is a foreign country – but in the twenty-first century, it’s one in which we increasingly seek solace. What fuels this love affair with recycling our history? What periods do we choose to romanticise, and how do our rose-tinted glasses occlude reality? Is all this nostalgia signifying – as the late Mark Fisher opined – the disappearance of the future?

In this edition, we explore the connection between loneliness, nostalgia and Big Tech and the ways nostalgia has been weaponised for political gain.

We revisit the heyday of advertising in the ’90s and investigate two long-standing editorial myths: have editors got worse? Do they infringe too much on the work of authors?

We talk with Melissa Lukashenko about the important role of historical fiction in recovering First Nations knowledges, experiences and stories, and learn from Witi Ihimaera about the ingenuity, mischief and gift for reinvention at the heart of Indigenous storytelling.

Griffith Review 83: Past Perfect surveys our need to idealise, sensationalise and glamorise – and asks what the circular nature of our obsessions says about our present cultural moment.

In this Edition

Nostalgia on demand

How then do we approach a circumstance in which it is possible to consciously curate those memories and sense impressions, such that they become mere features of our ‘profile’? Or one where third parties, having gleaned enough data to know us better than we know ourselves, can supply those memories and impressions for us?

James and the Giant BLEEP

It’s in this way that supposedly untranslatable words, for which our language has no exact or close synonym, are often so deeply pleasurable: not because those words reveal something about a worldview that’s unfamiliar or foreign to us but precisely the opposite.

The fall of the madmen

The problem with a fear-based workplace – and indeed world – is that caution and compliance are not compatible with creativity. Creativity searches for the things that have never been done before, on which, by definition, there is as yet no data. Scott Nowell argues that the obsession with data has made us lose faith in our own instincts, so it’s not surprising that creativity is not valued the way it once was. And the source of creativity has shifted to the consumers themselves.

Nothing ever lasts

But I hate thinking of myself as the diversity hire. As I said, I’ve worked in the industry for over a decade. ‘I belong in this room,’ I told myself. I’m not a token – despite being called that so many times in my career that I’ve lost count. I’ve earned my place.

Glitter and guts

All those years I had been excluded from the Anzac narrative because the Defence Act had outlawed Black enlistment. Lest we forget morphs into satire when you uncover the depths of collective amnesia surrounding Black service in World War I and Black resistance since colonisation. The more accurate catchphrase would be Best we forget. How can we be ‘one’ when we are not allowed to remember equally? Nostalgia is selective about remembrance.

Which way, Western artist?

Shadow for Zavros is cobwebby, a necessary concession to realism, avoided wherever possible. It manifests in surgical lines differentiating the contours of form from the seething morass of nature. Though Zavros indebts the modern Narcissus depicted in Bad Dad to Caravaggio, he has no affinity for the old master’s tenebrism; Apollonian form must triumph over Dionysian murk, lest all the fine things be swallowed.

Scarlett fever

The competition was notable for its shift away from being a Vivien Leigh lookalike contest. The bid to find a woman who, instead, ‘most closely’ resembled how Scarlett ‘would act and speak today’ and embodied ‘her spirit and sass’ opened up the search to any woman with a bit of chutzpah, including, in theory, Black and other women of colour.

Anticipating enchantment

When an editor works on a book, they balance reader expectations with what they interpret the author’s intentions to be and use their experience to make suggestions. This might mean changing some of the language to ensure the work is comprehensible for general readers, or asking for more detail where a setting has been hastily described. An editor will always be anticipating the market, and their extensive reading of contemporary works makes them well-placed not only to understand the social and political conditions of the day but also trends in publishing and marketing.

From anchor to weapon

In 1930s Germany, the slogan ‘blood and soil’ was most prominently promulgated by the Reich Ministry of Food and Agriculture, which positioned itself not merely as an administrator but a kind of advocate-guardian of the soil and its workers. In 1930, Adolf Hitler recruited Richard Walther Darré, then a leading blood and soil theorist, to the Nazi Party. On seizing power in 1933, Hitler appointed Darré Reichsminister of Agriculture, a role he occupied until 1942. Recently, for reasons that are unclear but politically alarming, Darré’s works on blood and soil have been translated and republished in English to some fanfare.

Farming futures

The tempo of seasonal food production gives Mildura its seductive groove. The race is on to get food to market when prices are high and before it wilts and rots. But this race is only incidentally about food and mainly about finance. When markets fail or supply chains are disrupted, harvests are bitter. Watermelons, zucchinis and lettuces are ploughed back into the ground. Grapes are left hanging on vines, sitting in coolrooms and rotting in shipping containers grounded at ports.

The ship, the students, the chief and the children

The power of the fossil-fuel order depends on foreclosing any kind of political and institutional decisions that would see societies break free from the malignant clamp of coal, oil and gas corporations. This power also depends on eliding alternative ways of seeing. In one sense, the whole of the political struggle against climate change can be understood as an effort to make corporate and political decision-makers see, such that they are required to act.

Walking through the mou(r)n(ing of a)tain(ted life)

My big black cloak could probably keep me from freezing overnight. I remember a movie where a character smeared a layer of dirt over their body to stay warm. That would be my ‘break in case of emergency’ action…if my OCD will bury the anxiety of contamination for survival’s sake.

Always was, always will be

If Aboriginal people are all dead, you don’t have to negotiate a treaty with us and you certainly don’t have to go around feeling guilty about stolen land and stolen wages and stolen children; the subjects of that injustice don’t exist anymore if you choose to believe that we’re dead or all assimilated, which isn’t the case. It’s a very practical kind of assimilation strategy.

The sentimentalist

I’ve positioned myself as somebody who’s constantly going through the trash of yesteryear with my raccoon paws and saying, ‘Wasn’t it grand?’ I think it’s more that I’m drawn to things I misunderstood rather than things that are just old, and I’m also interested in diagnosing the culture through what we loved, what we made and what we despised. It’s becoming much more clear to me the older I get.

Escaping the frame

All my work as a writer and activist over the last fifty years has comprised various attempts at what I call ‘escaping the frame of European colonisation, European story and European ways of telling story’.

Lines of beauty

I studied printmaking because in the mid-’90s there wasn’t so much exciting painting happening in QCA studios, but also because I really wanted to learn new processes for my undergrad and, like most artists, I’d always painted. Painting had fallen out of fashion, and everyone was making installation, then photography and film – the new digital world reigned supreme for a decade. Now it’s all about painting.

The kiss

With ears plugged and eyes closed, she felt safer. The sensations that did reach her were muted: the melodic ring of the seatbelt light being switched off, the rattle of the dinner trolley, the smell of food being warmed in microwave ovens – a heady aroma reminiscent of canned soup and sausage rolls. But above it all she heard something else. The rumble of a voice – low, male, foreign.American.

The green gold grassy hills

I’d missed her fiftieth birthday party the year before due to the usual restrictions of time and money. But as I stood at the window scrubbing vegetables, I wondered what had been so important that I hadn’t been able to make an exception for someone to whom a year could be a lifetime. Under-eights soccer game? Kids’ sleepover? But my partner could have done that on their own, couldn’t they?

Lost decade

We were given a list of verified addresses that we could pick from: Leonardo DiCaprio, Quentin Tarantino, Taylor Swift. I began my tours at Las Palmas hotel, where Richard Gere climbs the fire escape in Pretty Woman. Then I drove up Highland, past the church where Sister Act was filmed, and into the hills. The passengers were sunscreened and hopeful, leaning to the windows. My passengers, I reminded myself. I hadn’t even seen Pretty Woman then.

Apocalypse, then?

Writing took almost everything from me. Most afternoons, I’d arrive home from teaching classrooms of uninterested students, have a little Henry time, defrost a ready-to-eat supermarket meal, open a bottle of shiraz and write until midnight. Most weekends, I’d start writing once the hangover wore off, break for lunch, and then write again until dinner. It wasn’t just punishing on my physical health, it ruined my relationships, most recently with Greg, who said I’d die miserable and alone if I maintained my grim routine. And for what? The occasional acceptance from an obscure journal read by twelve other short-story writers?

In the Dollhouse

I don’t remember my Barbies, but Mother once told me I had twist-popped their limbs off. I do recall this one doll – she would wet her nappy if you fed her. I’d kohl a black full moon on the open sky of her forehead, but never feed her. There’s also the...

Cinema

I cry in the cinema Or not cry So hard that my head aches with the holding back Not in the film When those beside me weep Manipulated by the stranglehold of act three turning-point catharsis Or at the midpoint When the protagonist learns That he has been pursuing a false solution...

Pentax ME Super

History is a heavy handful

and a sore neck, but it

is safer than memory.

The emperor’s twin

In the absence of gods, must we choose monsters? You can never really know the difference, or see under. These creatures are all skin; hence history’s endless conjectures over The Man Within, as if the emperor had a smaller, kinder twin we’d never seen publicly. If we’d known what...

Threshold

What is the voice of one

who has died if no one listened to what

remained unspoken? It no longer matters.

Mildew on the whiteness of Hölderlin

Mildew on the whiteness of Hölderlin’s shoulders, his phantom limb reaching towards an ideal he is sure he’ll reach. When the snow comes I am not even sure if we’ll still be here, and what state the snow will present in – a white dusting on mildew, a statement of collected...

Things come together

After a photo by Annie Leibovitz of Johnny Cash with his grandson Joseph, Rosanne Cash and June Carter Cash, Hiltons, Virginia, 2001 It only takes a note, a few lines penned on a card, and the whole thing is salvaged. It might not say much...

Exeunt

The mirage of beer before their eyes.

Barney wipes his feet upon the mat

unaccustomed to such luxuries.