Featured in

- Published 20240206

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-92-4

- Extent: 203pp

- Paperback, ePub, PDF, Kindle compatible

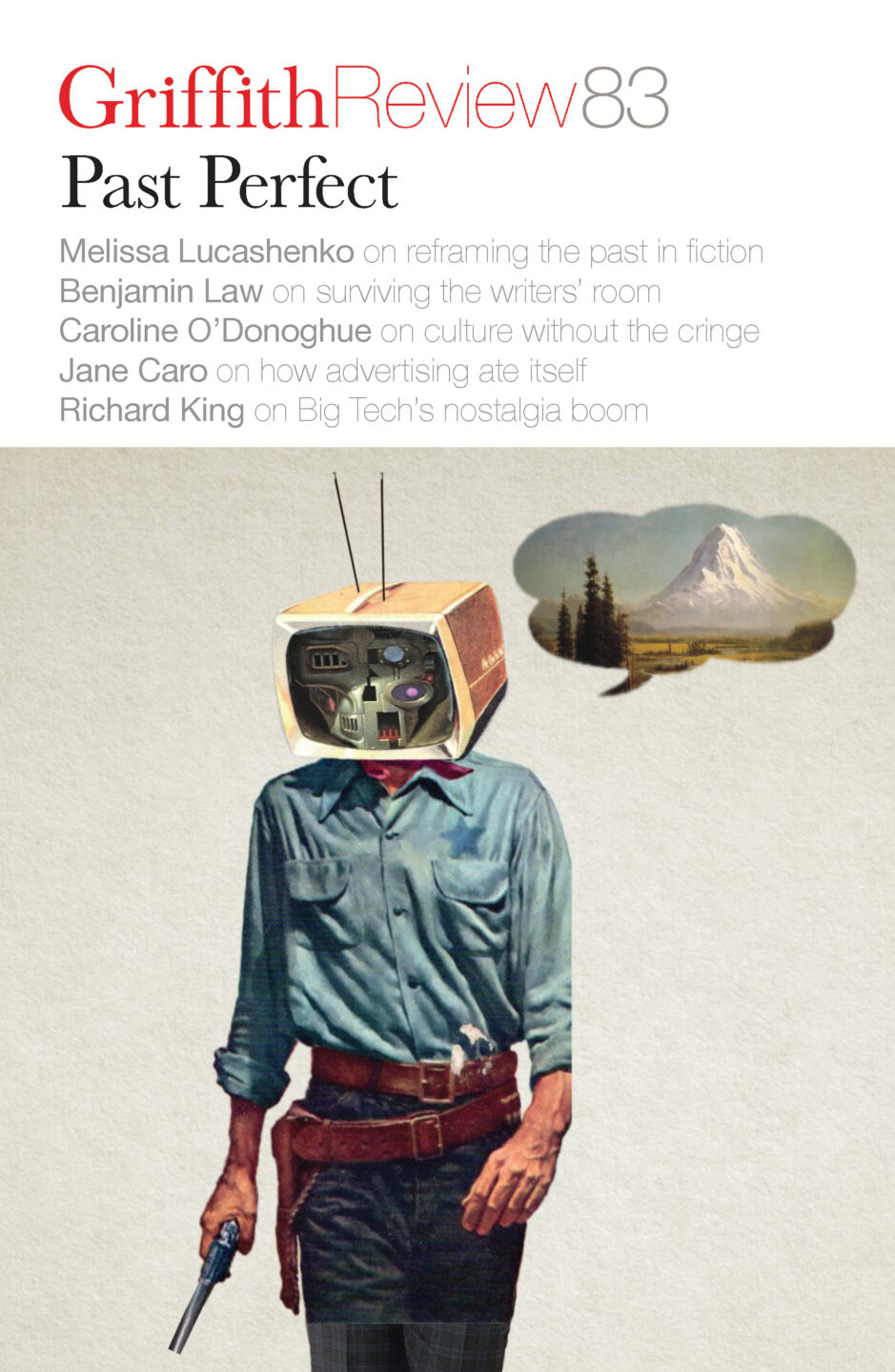

Michael Zavros, Bad Dad 2013, oil on canvas, 110 x 150 cm

INSIDE YOU THERE are two wolves. Their names are Mark Fisher and Camille Paglia. They are the only ‘philosophers’ you have read and basically understood.

You are at the opening of The Favourite, a QAGOMA survey of the artist Michael Zavros. There is a second show, Beautiful Wickedness by eX de Medici. Your husband is taking a picture on his phone of a cream puff that has fallen to the floor. He says this is art. You are anticipating the puff’s impalement by stiletto.

You have three hours to ingurgitate free champagne or ogle the art. Do you:

a) embark on a jaunt through Beautiful Wickedness, a rubbish tip of machine guns, plastic crap and skulls scrummed together like the Where’s Wally? book from hell. Avarice, exploitation and the (de)valuation of human life by capitalism are the exhibition’s baroque subjects; still, you can imagine these works wallpapering a celebrity’s walk-in robe in an Architectural Digest video. Do you feel:

i. nothing.

ii. confronted and/or challenged.

iii. guilty (constantly).

iv. as if the anti-capitalist project in art is not only redundant but insincere; there is no possibility of separating art from capitalism. As Mark Fisher writes: ‘The power of capitalist realism derives in part from the way that capitalism subsumes and consumes all of previous history: one effect of its “system of equivalence” which can assign all cultural objects, whether they are religious iconography, pornography or Das Kapital a monetary value.’ Visual artworks are the perfect expression of this capitalist logic; the creative product is most analogous to commodity. A thing can – in fact, must – be sold and bought, its value derived from its scarcity. An original artwork is, by definition, one of a kind. While other cultural products (television, music, clothing; to mention publishing is to speak ill of the dead) may lubricate the machinery of capitalism, the value they command in saturated markets is negligible.

By endeavouring to critique capitalist realism, eX de Medici’s work reproduces its logic, transferring its incoherence and banality to the canvas. Unable to meaningfully subvert the system, critical artworks instead adopt a posture Fisher describes as interpassivity (a term derived from Robert Pfaller). The artwork performs the viewer’s anti-capitalism for them, functioning as a pressure valve for material and moral anxieties. Critical artwork is thus an integral part of capitalist cultural production – because there is no revolutionary threat, the consumer-subject can have a little anti-capitalism as a treat.

b) choose The Favourite, likewise preoccupied with capitalistic excess but untethered from the moralism next door. Much has been made of Zavros’ fetishisation of luxury; virtually every critique of his work references conspicuous consumption, the tone usually finger-wagging (he’s not an artist, he’s a very naughty boy). The implicit moral doctrine of the superficially left-wing cultural industries dictates that artists should not engage with capitalism except as the site of critique, leading defensive admirers of Zavros’ work to interpret satire where it is not present. Designer shoes, suits and scarves are painted lovingly, the reproductions so precise that, looking at them, one can imagine how they feel to lick. It is possible to:

i. take this at face value. These are beautiful things painted beautifully, as Zavros himself claims (elsewhere, in conversation with Scott Redford in Eyeline, he says ‘artists should never open our mouths’). Until somewhat recently beauty was an acceptable justification for art.

ii. consider this in the context of capitalist realism. This requires a room-temperature IQ. The argument writes itself, and if there’s one thing you hate, it’s writing.

iii. behold them and spiral.

c) enter neither of the exhibitions but remain at the reception. Here you do not have to choose between champagne and socialism. On one side of the room Zavros and his assistants have painted the Acropolis; eX de Medici, bullets. The dialectic: we should all be lined up against the cradle of democracy and shot. Drinks cannot be taken into the exhibitions. They can only be guzzled here, in the no-man’s-land between opposing forces. And they are opposing; in form and ideation they are irreconcilable, and so this is perhaps the only way in the twenty-first century to have a polite debate – when the disagreement cannot be expressed through words. (Most people choose the champagne.)

YOU CHOOSE OPTION b) iii. The Favourite (if choices can only be articulated through the market, there is only an illusion of choice). Inside you are greeted by the first in Zavros’ Dad photographic series, wherein the artist’s plastic golem – a 3D-printed, life-sized or slightly taller mannequin – reclines behind reflective sunglasses. You hear the strains of Lady Gaga’s ‘Paparazzi’, earworm torture of the sort favoured in Guantanamo Bay (in another room, Zavros’ daughter lip-syncs to the song in a home video). You pass the miniature paintings of suit cuffs, re-creations of yuppyish GQ magazine adverts; an oil painting of cologne bottles, designer shoes and sunglasses, arranged in the shape of a skull. There are ‘self-portraits’ featuring the model Sean O’Pry – the love interest in the music video for ‘Blank Space’ by Taylor Swift, itself set in Zavrosian hyperreality – and then you re-encounter dummy Dad, photographed surrounded by his flesh-and-blood brood.

These exhibits characterise the exhibition’s themes: family life and the fetishisation of objects. You might interpret this as:

a) the evolution of the artist through fatherhood. The young man who painted the fine things has mellowed, been normalised. Whatever excited him to paint the superficial subjects of his early work is eclipsed by domestic concerns. In Nietzsche’s words, ‘The angry and reverent spirit peculiar to youth appears to allow itself no peace, until it has suitably falsified men and things, to be able to vent its passion upon them.’ The younger images are frozen, petrified objects refuting age and decay. The clothes depicted in fashion advertisements are objets d’art, existing in the sterile suspension of a studio photoshoot: immortality as consumer good. But for a parent – someone who keenly feels the passage of time as they observe their growing children – this is a perverse fantasy. The child who is not in a constant, perceptible state of change is dead (see Phoebe Is Dead/McQueen from 2010, which depicts Zavros’ daughter Phoebe lying corpse-like beneath an Alexander McQueen skull-print scarf).

b) a natural continuation. The object of fetish has transferred from consumer good to the ultimate luxury product: a beautiful life, replete with beautiful family. The works in The Favourite depict gorgeous objects, glistening pearls strung on a thread of narcissistic will. Like Medusa’s, the artist’s stare is petrifying. It turns on his children not because Zavros has succumbed to sentimentality – as the anthropologist Margaret Mead says, fatherhood is a social invention – but because his criteria for object selection have become sophisticated. Fisher’s argument is taken to the extreme; the family itself becomes commodified, integrated into a system of equivalence alongside shoes and suits.

THE NEXT CHAMBER is populated with floral still lifes. These are not your grandma’s still lifes; Margaret Olley, whomst? The obligatory descriptions emblazoned on the wall, with their insistence on whimsy and play, are insane. You think of the Italian poet Gabriele D’Annunzio, heralded by Mussolini as the John the Baptist of fascism, who rearranged the flowers at his bedside three times a day.

Sculpting the flowers into animal silhouettes – octopus, poodle, lobster – the artist sneers at nature as a purveyor of inferior forms. Zavros acknowledges this: interviewed by Rhana Devenport in 2014, he referred to the paintings as ‘baroque folly, nature made better, more pretty’. The designer dog featured in The Poodle (2014) is both overbred and cross-pollinated. With its fleecy coat of hydrangeas and shapely Waterford Crystal legs, the neutered hound can only sit and stay (in another painting, The Greek, Zavros arranges vase and hydrangeas into a phallus with big, fluffy balls; the stems visible inside the vase are the dorsal veins of a glass penis).

Frigid and ectomorphic, the bouquets are centrepieces – in what? Where? Another white-walled gallery, more exclusive than this venue, where copies are exhibited by the state? With no contextualising environment the florals are fetish objects, arctic and lapidary. Their visual logic is that of a stocking wanked over by someone who has never seen a thigh. Suspended in white space, the flowers are as unnatural as those photographed by Robert Mapplethorpe. Nature as vaginal flower is mummified into hard, glowing object, the traditional tribute of lovers excised of fleshy sentimentality. The blaspheme of Mother Earth is crystallised in the skeleton giving voguish shape to White Peacock, the bones stripped of meat as if by nuclear cataclysm. The roses and dahlias remain intact, perfected like diamonds by heat and pressure.

Writing about this exhibition in The Conversation,Sasha Grishin claims ‘It is difficult to view pieces including The Poodle (2014) other than as a critique of a society completely out of control and sacrificing function for the sake of cute design.’ Okay, Sasha. Zavros’ self-professed motive echoes the philosophy of Camille Paglia of art and civilisation as contest between Apollonian form and Dionysian nature. Paglia defines the Apollonian as the ‘hard, cold separatism of western personality and categorical thought… Apollo is obsessiveness, voyeurism, idolatry, fascism – frigidity and aggression of the eye, petrifaction of objects.’ For Paglia, the Apollonian is emphatically masculine, a productive manifestation of male sexual anxiety. Feminine nature is generative: no placid, Rousseauian idyll, but a wildly maximalist totality. The Apollonian is its compressed sadomasochistic parody. So do you:

a) concur with Grishin. (Most of) Zavros’ work is explicitly capitalistic; not a bad idea. If the contemporary artist wants to make a living from his work, he might as well depict things that will not give his patrons nightmares. A beautiful thing painted beautifully will not disrupt the equilibrium of a living room, a toilet, an Eyes Wide Shut orgy, a state-of-the-art storage shed where pieces are stowed for tax purposes. The sacral figures of Western art – the Renaissance masters – understood this; they made sure their work reflected their patrons’ contradictory desire for decadence and spiritual piety, while injecting it with hallucinatory avant-garde flair.

b) concur with Zavros’ admitted intention, the editorialisation of nature. If the paintings depict a (futile but vigorous) struggle of Apollonian form over Dionysian nature then this predates capitalism by millennia, and so cannot arise from its logic. The capitalist trappings of Zavros’ work are era-specific expressions of an ancient, abiding preoccupation with an aristocratic hierarchy of aesthetics: though nature can create more beautiful things than man, only he/she/they can be a connoisseur. This, more than the post-critical attitude to capitalism, is why Zavros infuriates sectors of the art world. To admire beauty is to admonish ugliness, ascribing moral value to aesthetics. (Ironically this attitude, originating in modernism and embraced by the so-called left, is perfectly suited to capitalism, conferring on it the moral right to produce inexpensive, uglier things. The subjects of capitalism participate then not out of desire, even manufactured desire, but out of the moral compulsion of

the indoctrinated.)

The primary charge levelled at Zavros, and photorealistic painting generally, is that it is surface level – a charge he has elided by making surfaces his subject. As an artist friend of yours argues, anyone with the time, resources (that is, assistants – a whole other essay about exploitation and labour relations, which – whatever) and technical skill could create a photorealistic painting. Though this has mass appeal you argue that the genius of Zavros’ work is in the unity of form and conceptualisation. While it is realistic it is not natural; familiarity is the precondition for the strange. (Familiarity tickles your inner etymologist, as does family: the Latin root describes not cosy, nuclear relations, but servitude to the master of the house.)

THE CENTRAL ROOM of The Favourite is devoted to Zavros’ family. Because it is a parody of a living room it follows that it is a dying room, equal parts family photo album and fabulous dynastic crypt. At the centre of this holy of holies is his ark of the covenant, the sculpture Drowned Mercedes: a flooded Mercedes Benz SL-class drop-top, from which security guards repel admirers. You desperately want to climb in or open the door. The license plate reads AGAPE, which your drunk husband reads as a-gayp. When you tell him that a-gah-pay is the ancient Greek word for love – the perfected, selfless form later endorsed by Christians, including CS Lewis, as superior to horny eros – he responds that a-gayp is funnier. (Your dad does not find it funny when you tell him what this artist has done to this car.)

Drowned Mercedes is the only artwork in the room that gestures explicitly to capitalism. It is adolescently provocative (your friend describes Zavros as an edgelord, a term popularised on 4chan in 2014, when Zavros was forty). The wordplay licence plate links the sculpture to the painting Amore (2018), wherein Zavros’ glamourised daughter Phoebe supernaturally elides the transition from girl to woman (in Greek myth, goddesses emerge fully formed from the father, in feats of onanistic conceptualisation: brainy Athena by blow to the head and sensual Aphrodite by castration). Rouged, with a voluminous blowout, Phoebe wears a shirt with AMOUR embroidered on the collar – not amore, the Italian title of the work, but amour, understood since the sixteenth century to refer to an illicit affair. Nearby, in Rom Com (2023), Phoebe beams coquettishly as she pulls at dummy Dad’s tie; what at first appears to be a pin on the sleeve of his suit is a fly, drawn to Dad’s mephitic carcass. Incest and necrophilia, and…look over there! It’s the former Governor-General, Dame Quentin Bryce. Agape, agape, amore, amour. The reflective surface is a two-way mirror.

What is the reason for this pivot, from giddy consumerism to ambivalence? Is it that:

a) the artist, having made his name as a documentarian of the superficial, seeks to establish depth.

b) things that once seemed beautiful – clothes, horses, nihilistic floral arrangements – pale in comparison to children, beheld in the dewy eye of their doting dad. The parent’s irreconcilable project is to protect the flesh of their flesh from harm while guiding them towards the long decline of adulthood: for dust you are, and to dust you shall return (Genesis 3:19).

c) there is no pivot. The work was never about capitalism. The miniature paintings, nominally indebted to magazines, replicate a mode popular with European royalty of the seventeenth century. The exhibition’s title, The Favourite, situates it in the system of courtly economics, which even the most ardent Marxist-Leninist would concede is more unjust than capitalism. In this way Zavros’ rejection of capitalism is more radical and reactionary than eX de Medici’s. It aligns with the vision of alt-right darling Curtis Yarvin, an advocate for neo-monarchy. By dangling the shiny things of late twentieth-century capitalism, Zavros distracts his critics from an altogether more sinister political vision. Meaning that:

i. the work is highly political, but its politics are inconceivable to the liberal, capitalist subject (and we are all liberal, capitalist subjects) and therefore they are misconstrued as capitalist apologia.

ii. the work is not political. It is an unfortunate reality that the ideals of the aesthete dovetail with those of the fascist, hence the well-documented relationship between classical aesthetics and fascism. Theodor Adorno is often misquoted as saying that there is no poetry after Auschwitz. The actual quote, ‘to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric’, obfuscates that the creation of art has always required a refined sense of barbarism (in the word’s modern sense – etymologically it describes one who does not speak Greek).

iii. the artist cannot have politics, by virtue of being an artist, but can only be beholden to politics. Though paintings like Mum’s Wedding Dress (2021) recall the society portraits of John Singer Sargent and Valentin Serov in composition and in the blend of verisimilitude and smudgy impressionism, the artist’s status in society is contingent. Whoever his master is, the favourite is an extravagant pet.

THE MOST STRIKING painting in this room is titled Zeus/Zavros (2018). It hangs alongside Bad Dad (2013), the uncanny self-portrait in which Zavros depicts himself as inner-suburban Narcissus. Head bowed in aquiline profile, Zavros in Bad Dad resembles Christian Bale as Patrick Bateman, whose creator, Bret Easton Ellis, is referenced elsewhere in Zavros’ oeuvre. While Ellis’ novel American Psycho remains banned in Queensland, Zavros commands its state art gallery; Bad Dad, his Bateman-esque self-portrait, was a finalist in the Archibald Prize. Comparison between the two men is illuminating – the artist who expresses his ideas verbally is more likely to be subject to censure, due to the literalism assumed of language, even of satire. The visual artist, communicating through the image, maintains plausible deniability – a notable exception being Bill Henson, also referenced by Zavros; one of his photographs is depicted in the painting The Lioness (2010).

Zeus/Zavros is one of a suite of paintings that recall the scandal ignited by Henson’s photographs of young girls (scandal Zavros courts with Phoebe Is Dead/McQueen). The notable difference is that Zavros’ subjects are his own children. Should anyone remark that these depictions are eroticised, he is armed with a brilliant rebuttal: why are you eroticising my kids, you pervert? Despite his insistence in the blurb accompanying Bad Dad,the artist cannot paint solely for himself; the viewer’s implication in the act of seeing is anticipated. Perhaps for this reason there is little published commentary about Zavros’ family paintings, though there is plenty of gossip, the low-hanging fruit of capitalistic excess being easier game for the intrepid art critic.

Zeus/Zavros is the darkest painting in The Favourite, literally. Tilting her face to the sun Phoebe hangs draped from the neck of an inflatable pool toy, her nude brother prostrated on the back of a blow-up swan. Where the rest of his oeuvre abhors chiaroscuro in favour of blinding exposure, more than half of Zeus/Zavros is engulfed by shadow. Shadow for Zavros is cobwebby, a necessary concession to realism, avoided wherever possible. It manifests in surgical lines differentiating the contours of form from the seething morass of nature. Though Zavros indebts the modern Narcissus depicted in Bad Dad to Caravaggio, he has no affinity for the old master’s tenebrism; Apollonian form must triumph over Dionysian murk, lest all the fine things be swallowed. Still, the objectifying amoralist cannot help but be contaminated by the vision of his daughter as Leda, raped by swan-Zeus; his corruption spills across the canvas, an inky oil slick.

The predominance of shadow in Zeus/Zavros reveals more than it obscures. Here Zavros the artist concedes to the neuroticism to which Robert Leonard considers him immune when he describes him as ‘a well-heeled, high functioning pervert’ (2011). Is the atypical shadow:

a) a confession of moral anxiety – not for having painted Zeus/Zavros, but for having conceived of it.

b) a calculated manoeuvre of pre-emptive defensiveness.

c) another self-portrait. Zeus/Zavros shares one feature uniting it with the depictions of Zavros showcased in The Favourite, including the adjacent and literal Bad Dad: when painting himself, Zavros never meets the viewer’s eye. His gaze is obstructed, pitched elsewhere, or obscured by sunglasses or medallions of cucumber. The adult recuses himself to the plane of imaginative play, while the children confront reality – that is, the viewer. Perhaps the titular Zeus is the swan, a creation of Apollonian idealism, and Zavros his daimon, the Dionysian shadow – engulfing his scions like Kronos, the cannibalistic child-eater, father of Zeus.

d) hauntological, a spectre; in Fisher’s words, ‘not so much [of] the past as all the lost futures that the twentieth century taught us to anticipate’. The imaginative violence of antiquity, synthesised into Apollonian form, has no relevance in the twenty-first century. As eX de Medici demonstrates, modern violence is systemically distributed and bereft of glamour. The king of the gods is a plastic pool toy; no Leda was harmed in the making of this image. Pastiche and reiteration do not signal nostalgia (in Greek, the ache of homecoming) but an ironic disavowal of the present.

THOUGH IRONY IS perceived as a modern malady, it too derives from ancient Greek: Socrates pretending ignorance to expose another’s. To sincerely evaluate the symbolic content of these paintings is to make oneself a victim of irony, too often confused with satire. The modern iteration of irony, or affected ignorance, drives not at truth but at chic, a phenomenon Susan Sontag described in ‘Notes on “Camp”’(1964). It is not a conscious attitude, but a defensive posture adopted against the fact that certain knowledges are lost. In this sense it is certainly not unique to postmodernism.

By the time of Leda’s popularity among the Renaissance artists her motif was only that, hence da Vinci’s almost obscene prettification of what was to ancient cultists a scene of bestial violence, the prologue to the perfected violence of the Trojan War (Leda birthing Helen from the rape). As Richard Wagner writes in 1880 in Religion and Art:

what could now be borrowed from the ancient world, was no longer that unity of Greek art with Antique religion whereby alone had the former blossomed and attained fruition… Greek art could only teach its sense of form, not lend its ideal content; whilst the Christian ideal had passed out of range of this sense-of-form, to which the actual world alone seemed henceforth visible.

In this way you are led back to capitalist realism. Without belief in the supernatural, or the sublime, or anything, what can art depict but the visible world – the only thing left in which to believe? Can art be anything but ironic, even art as earnest as eX de Medici’s? We are too clever to believe the superstitions of the past and too stupid to recognise superstition as an epistemology to which we no longer have access. The only choice, if one can call it that, is to believe the visible world is:

a) an infernal machine, à la eX de Medici.

b) impossibly beautiful, and beneath that beauty, nothing.

In this belief, more than form or historical references, Zavros inherits classical and Renaissance traditions. His paintings are formal expressions of faith, without which they could not be conceived. They are religious artworks – from the religion of modernity, which is not an absence of belief, but a devout belief in nothing. It is a belief in no future, no past; about the present it is agnostic. Adherents of the faith surround you; its hymns reverberate. Padam. It is the goddess, Kylie. Padam. You hear it, and you know:

a) Padam, the show is over.

b) Padam, the bar is closed.

c) Padam, it is true, as Nick Cave says of ‘Better the Devil You Know’, that ‘love relationships are by nature abusive…this abuse, be it physical or psychological, is welcomed and encouraged…the most seemingly harmless of love songs has the potential to hide terrible human truths’.

d) Padam, this is the last prayer, the only plea you may offer to the god/dess/x of nothing; the onomatopoeia of the heartbeat.

Share article

More from author

Quinoa nation

FictionWe don’t stock Gwyneth Paltrow’s cookbook. I know this because Amanda thinks Gwyneth Paltrow is goofy, despite Amanda and Gwyneth Paltrow being the same person. Our customers are Gwyneth Paltrow’s target demographic. If Gwyneth Paltrow wrote a novel our book club would literally devour it.

More from this edition

Anticipating enchantment

Non-fictionWhen an editor works on a book, they balance reader expectations with what they interpret the author’s intentions to be and use their experience to make suggestions. This might mean changing some of the language to ensure the work is comprehensible for general readers, or asking for more detail where a setting has been hastily described. An editor will always be anticipating the market, and their extensive reading of contemporary works makes them well-placed not only to understand the social and political conditions of the day but also trends in publishing and marketing.

Exeunt

PoetryThe mirage of beer before their eyes. Barney wipes his feet upon the mat unaccustomed to such luxuries.

Lines of beauty

In ConversationI studied printmaking because in the mid-’90s there wasn’t so much exciting painting happening in QCA studios, but also because I really wanted to learn new processes for my undergrad and, like most artists, I’d always painted. Painting had fallen out of fashion, and everyone was making installation, then photography and film – the new digital world reigned supreme for a decade. Now it’s all about painting.