Journal

Articles

Songs of the underclasses

Before his back deteriorated for good, Diē had imagined becoming a tour guide in his retirement years. To this end, he farewelled our geriatric SUV and bought a fourteen-seater HiAce. After I got my P-plates, he pulled out the back two seats so I could drive it legally and insisted I go on long drives – though never unsupervised. Wǒ zhīdào bu lōgǐcǎl, dànshì méibànfǎ, said Diē. Nǐ shì wǒ de nǚ’ér. ‘I know it’s illogical, but you are my daughter.’

Diē was the best driver I knew. ‘When you drive, you stare at everything but see nothing. You’re inexperienced,’ he lectured. ‘When I drive, I stare at nothing – I can chat, I can sing. But I see everything. Parking spaces, jaywalkers with a death wish, doggies and kitties. And for hours at time, without breaking concentration. It’s like meditation.’

Diē’s love language included showing me footage of near-miss traffic incidents on WeChat. Each trip of ours decreased my risk of appearing in his feed. These hours became the most time we had ever spent together. ‘I write stories too,’ said Diē, during one of our drives. It was early 2024, and he was accompanying me to a writing workshop in Parramatta.

Mudth

My family has its roots in several parts of the world: the Lui branch in New Caledonia, the Mosby branch in Virginia in the US, and the Baragud branch in Mabudawan village and Old Mawatta in the Western Province of PNG. Growing up, I spent most of my childhood with my Lui family at my family home, Kantok, on Iama Island. Kantok is a name we identify with as a family – it’s not a clan, it’s a dynasty. It carries important family beliefs and values, passed down from generation to generation. At Kantok, I learnt the true value and meaning of family: love, unity, respect and togetherness. My cousins were like my brothers and sisters – we had heaps of sleepovers and would go reef fishing together, play on the beach and walk out to the saiup (mud flats). I am reminded of these words spoken by an Elder in my family: ‘Teachings blor piknini [for children] must first come from within the four corners of your house.’

One language among many

I first used speech-recognition software in 2012. I was about to begin work on my novel The Crying Place, and I wanted to get closer to oral forms of storytelling – a sitting-around-a-campfire feel to the text. Also, I was intending to draft much of it on the road from Naarm (Melbourne) to Mparntwe (Alice Springs), then later in the desert, a moving vehicle not being the easiest place to type.

The software took a bit of getting used to. I had to train it to decipher the idiosyncrasies of my voice by reading texts out loud and using it in different environments. And I had to get the hang of directly narrating the story in character – a form of oral ‘method writing’… What soon became clear was that sounds other than my voice, such as birdsong and wind passing through trees, were being picked up by the software and ‘translated’ into words. Mulga came up as ‘will will’, desert oak as ‘with with’, birds varying according to song. At first I deleted these words from the text – treated them as errors or intrusions – but gradually I recognised what they were showing me. The direction the wind was travelling. The proximity of birds and their conversations, sometimes interspecies. Other languages.

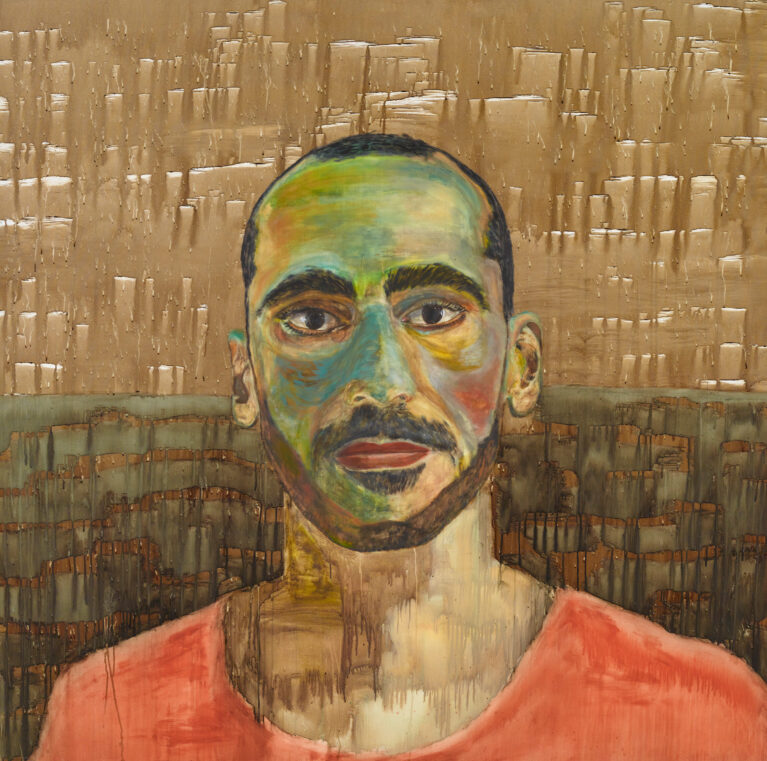

Painting behind bars

Every time I grab a toothbrush, it makes me smile that [this all began] at Manus. I mean, this technique comes from suffering. This is not from university. I am forbidden from studying or getting a qualification here, but sometimes we can learn from suffering. I am managing to heal my trauma [with] painting. Whenever I feel sad, I paint. Whenever I feel happy, I paint. It’s like a treasure, how can I explain it? It’s invention, it’s something that hasn’t happened before. Everyone uses a toothbrush, but when I paint with a toothbrush I feel it helps me understand that my work, the marks I make, are very unique. It brings the story back. I don’t want people to forget about the story because I don’t want to escape from who I was, who I am. I would like to share the truth that this happened to me.

Dining in

The intimate, private setting naturally creates a close connection between the chef and diners, making it easier for the chef to share the stories, heritage and traditions behind each dish. For diners, the cosy, welcoming atmosphere makes them feel as though they’ve been invited into a friend’s home. From a business perspective, a home-based restaurant comes with fewer overhead costs, such as rent and wages. This allows me, as the business owner, to deliver high-quality food at a more affordable price, as these expenses are not factored into the food cost.

The blue room

Mum did not tell us that Sabina had tried to kill herself. She said that she was unwell, and because she was unmarried and her children lived interstate Sabina would stay with us while she convalesced. We figured it out after she arrived; she did not appear sick, but lively and plump. Nor was there any regularity to her medical appointments. Though Phoebe was irritated that she would have to share her bathroom we found the situation morbidly glamorous, the sick woman with the elegant name whose stay would end with recovery or its opposite. So many sibilant words: suicide, convalescence, Sabina. Having no knowledge of death or any conviction we would ever die, suicide seemed tinged with romance. That Sabina lived confirmed our belief that death was not serious.

The pool

Mum always says to me, you know what he’s like – your father. As if the old man is my responsibility and mine alone. Little wonder that legacy and liable have the same number of syllables. Of course I know what he’s like…so much so that I’m not even remotely surprised when one afternoon I hop off the school bus and come wandering inside with my little brother Jeremy in tow to find a big bald bloke sitting cross-legged at the dining table blabbering on about fibre glass this, solar heating that. On the table in front of Dad, a corona of shiny brochures.

‘We’re getting a pool, sons!’ Dad winks at Jeremy.

Trash and treasure

In the middle of the night he had a dream where the dirty pasta bowls he’d left out were on fire, smoking up the apartment. When he shot up in bed, he could still smell the smoke. He remembered Karim, the whole previous day and night flashing through his head. In five strides he was in the living room. Karim wasn’t on the couch. The balcony door was open and he was out there, shirtless, leaning on the balustrade smoking a cigarette. The nodules rising out of his spine pinged the moonlight over his back like a prism. Ben went out, shut the door behind him, leaned over the balcony by Karim. Their arms touched and neither of them pulled away. The forum was emptier than empty. Completely still, like they were peering into a photograph.

Sissys and bros

‘Sydneysiders woke up to a red dawn this morning due to an eerie once-in-a-century weather phenomenon.’ This was straight after school, before my shift. Channel 9’s Peter Overton was blaring from the TV. My five sisters and two brothers yelled about Mumma hogging the remote. Overton’s robot voice followed me into my room. I tugged off my Holy Fire High School blazer. Our emblem: Bible beneath a burning bush. Our motto: Souls Alight for the Lord and Learning. Fumbled through the dirty laundry basket for my dress-like work shirt that stunk of rancid onion. Our logo: a pepperoni pizza wearing a fedora and holding a Tommy gun. Our motto: Happy Mafias Pizza: Real Italians Leave the Gun and Take the Cannoli.

Load

When I wake up from being a dishwasher, curled on the floor of my apartment, it’s like I have woken from the perfect slumber. I don’t think I have felt like this since the womb. Imagine being able to temporarily kill yourself. The world, the body, weighs heavy. Being a dishwasher is the closest I have ever felt to bliss. Before this, the closest I got to bliss, true bliss, was getting high with my dad and eating a cream corn and cheddar toastie at the Murchison Tea Rooms.

Mesopotamia

Their camp is on a floodplain, dirt baked dry for now, among a stand of black box trees. Close to the bank, river red gums tower and would provide better shade, but Kim had been worried about falling branches. From a rise near their tent, they can monitor the vast, slow drift of the watercourse, progress marked by its bobbing contents. Wordlessly, this is how they spend most of their time.

Bellend

‘Nice little bell, buddy,’ snipes some guy holding space in the bike lane as I nearly swipe him on my way...