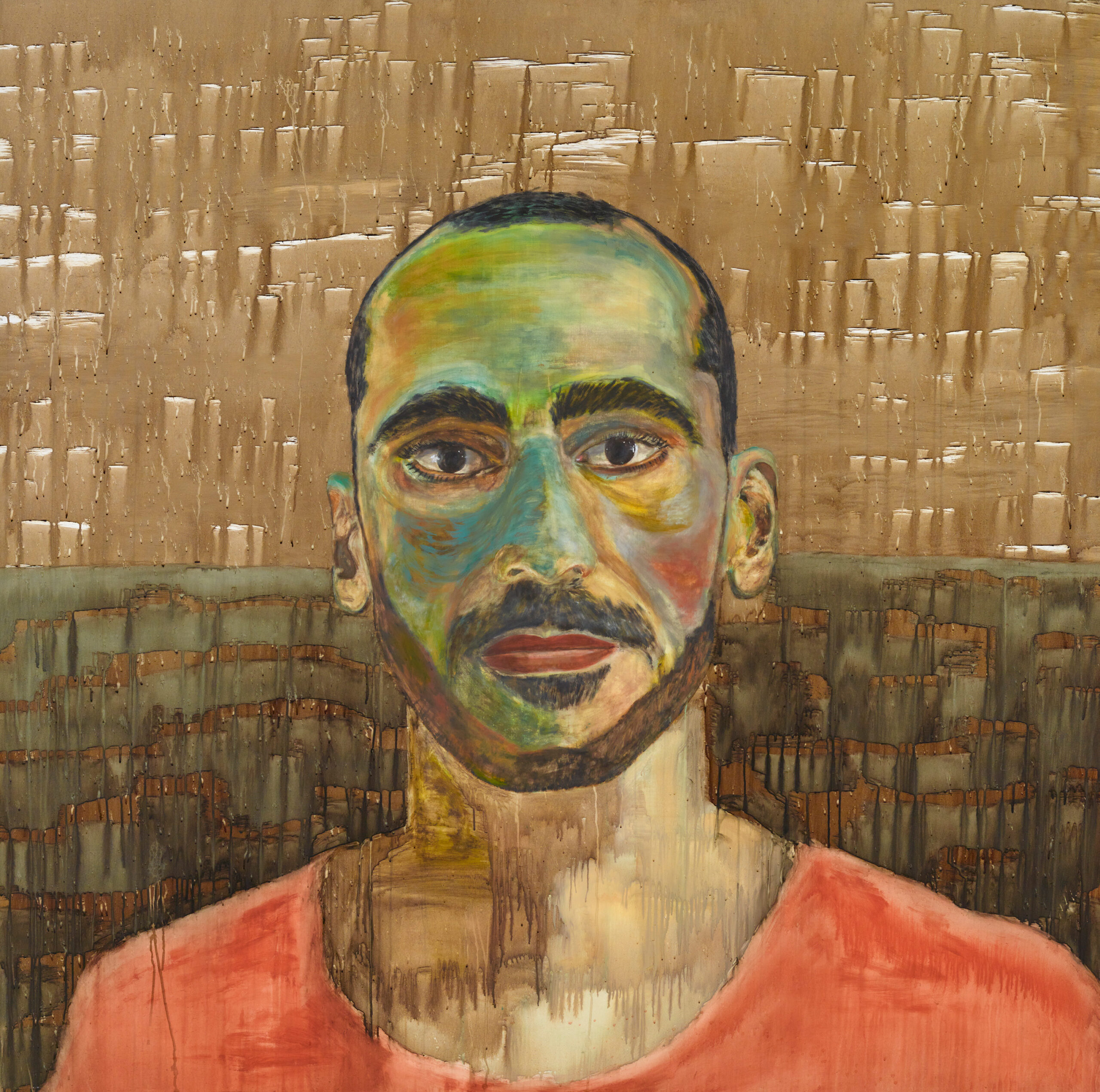

Painting behind bars

The art of fighting for freedom

Featured in

- Published 20250204

- ISBN: 978-1-923213-04-3

- Extent: 196 pp

- Paperback, ebook. PDF

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

About the author

Mostafa Azimitabar

Mostafa Azimitabar is a human-rights activist and two-time Archibald Prize finalist. As a refugee from Kurdistan, his status as an Australian resident is yet...

More from this edition

Bellend

Poetry ‘Nice little bell, buddy,’ snipes some guy holding space in the bike lane as I nearly swipe him on my way to the shops. Low and...

Blackheath mating rituals

Poetry Clouds ripple, sunshine splashes, a white dove tests its wings. Bella and Houdini are hanging clothes on the line of the landlord when flirtation greets them: the...

Steering upriver

Non-fictionAt dawn I cross the bridge, Missouri to Iowa, and turn down the gravel drive. Though I’m different now, this place is the same as it always is this time of year: the sun glowing red over the paddock next door, the grass not yet green, the maple stark. I go away, come back again, and home is like a photograph where time winds back, slows into stasis; where the carpet has changed, but the dishes have not, the cookbooks have not, the piano and artwork and bath towels have not. Here, I can be a child again, my best self, briefly. I hold on to this moment for as long as I can, because too soon I’ll remember how disobedient I am, how bossy and domineering, how I slammed my door until Dad took it off its hinges, how soap tastes in my mouth, how I pushed on these walls until they subsided.