Welcome to GR Online, a series of short-form articles that take aim at the moving target of contemporary culture as it’s whisked along the guide rails of innovations in digital media, globalisation and late-stage capitalism.

Very online feelings

In 2013, the Oxford English Dictionary declared ‘selfie’ its word of the year, and Twitter later declared 2014 ‘the year of the selfie’ after the term was mentioned more than ninety-two million times on the platform – a twelve-fold increase from the previous year. It was in this context that influencer selfies provided templates and scripts to spur more consumption and more desire, taking commodification of the body and the self to the next level. For instance, influencers popularised a whole ‘science’ around how to craft the most desirable faces through cosmetics and surgery, how to perform authenticity through ‘casual selfies’ that felt extra sincere but that also required extra behind-the-scenes effort, and how to assuage tensions arising from accusations of excessive plastic surgery and ‘fakery’. Selfies were reclaimed, transformed by their creators from expressions of mere vanity to useful tools of subversive frivolity. Influencer couples also sold us benchmarks of romantic perfection through carefully orchestrated couple photographs, love declarations on social media and ‘rules’ about how to be the perfect partner.

It ain’t easy being twee

During my pre-teen years, I amassed a large collection of animal plushies and figurines. I loved collecting different species, different families and different genii. I didn’t just want a generic teddy bear, I wanted specific representations of the animal kingdom: grizzly bears, black bears, sun bears and so forth. (FYI: in earlier decades, it was hotly contested whether giant pandas were true bears or were closer to their raccoon relatives, so my panda plushie split its time between families.) My plushies were ‘decluttered’ when they were no longer ‘age appropriate’. I was expected to become a different kind of person – one who doesn’t think about plushies. One who can get by on utility, with no need for art, beauty or whimsy. One who can use their perspicacity for something sensible. It wasn’t to be. My dad’s influence failed miserably – emphasis on misery. Or, arguably, it swung me further away, back in the direction of my grandparents, imbuing my possessions with sentience, value and personality. I find it unbearable to let anything go.

Know thyself

We spoke to the genetic counsellor and the doctors. I had more than a 70 per cent risk of breast cancer and close to a 50 per cent risk of ovarian cancer in my lifetime. This would require vigilant surveillance, but with ovarian cancer there is no reliable screening method. It can already be advanced before it’s detected, which is what happened with my mother.

My mind kept taking me back to those sandy ruins and the Pythia. Those characters in mythology who tried to avoid their fate even when she had given them the answer. You can run but you can’t hide from destiny. Enter the acts of dramatic surgical intervention. Like a deus ex machina, but without the gods, just the science.

Culture warrior

It’s safe to say, then, that Star’s protagonist is not a carbon copy of Mishima, despite the novelist’s status as Japan’s first Sūpāsutā (superstar). Twenty-three and blindingly gorgeous, Rikio Mizuno, known by the anglicised monomer Richie, is a Japanese James Dean. ‘I am a speeding car that never stops,’ Richie muses, conflating the icon with the instrument of his death. ‘I’m huge, shiny and new, coming from the other side of midnight… I ride and ride and never arrive.’ Unlike Dean, Richie survives past his twenty-fourth birthday, the addition of a single year weighing on him like a death sentence. At the story’s conclusion, when Richie is confronted by the crinkled visage of a matinee idol of yesteryear, he realises that having celebrated the twenty-fourth birthday Dean was denied by his Porsche 550 Spyder, ‘Little Bastard’, he has missed his chance to, as Dean said, ‘Live fast, die young and leave a good-looking corpse.’

Anyone who has been to a gay guy’s thirtieth birthday party will recognise the sentiment.

The accidental film school

The DVD format – the Digital Versatile Disc – was invented in 1995 and reached the peak of its popularity in Australia in the 2000s, before the rise of streaming platforms in the 2010s. During those salad days, Australian entertainment companies started producing and selling DVDs at a rapid rate, building a library of local and international films. The Melbourne-based company Madman Entertainment were competitive players... The extras on their DVDs – making-of documentaries, deleted scenes, audio commentaries – allowed producers to have an active role in the historicisation of film; audio commentaries typically featured directors and actors rewatching and reminiscing together. But companies like Madman (and Criterion in the US), which distributed ‘art-house’ cinema, were more likely to invite film theorists and historians to provide an analytical reading of the film as it played.

A freer state of being

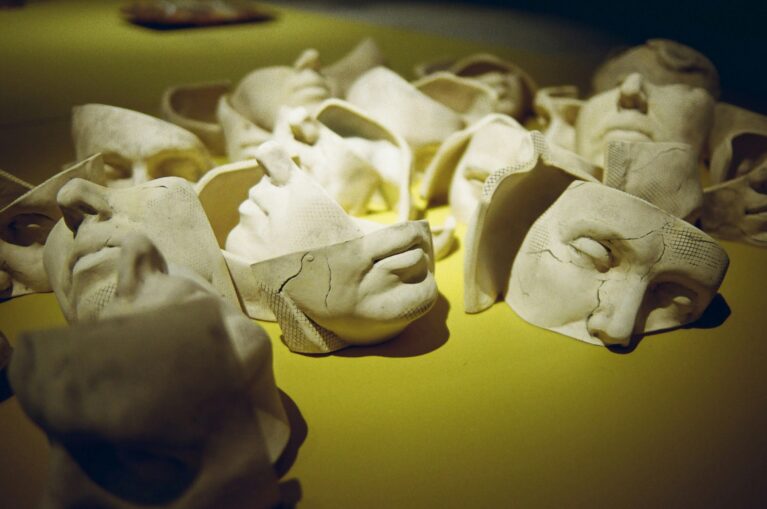

Today, we live in a time in which self-worth and value are often signified by a numerical figure – how many followers we have, how many likes we receive, what level of traction our posts incite. We live in a time in which this numerical figure equates to social capital, with digital ‘celebrities’ gaining varying levels of access to places and perks on the basis of their following. We live in a time in which the aesthetics and metrics of this burgeoning digital realm pervade and influence not only the way we live our lives but what we perceive to be reality. We understand ourselves and the world around us through the cultural codes, signs and symbols we consume. We depend upon and wield such cultural codes, signs and symbols to inhabit narratives in which we wish to belong, fashioning them like an armour that tells the world who we are. Appearances are everything.

But hyperreality is an unstable landscape. When our cultural codes, signs and symbols give way, so too do our carefully curated identities, which inevitably implode.

Less than human

What elevates Miku and makes her significant in our cultural landscape is her accessibility. Unlike traditional celebrities, who, even if they want to be accessible to their fans, only have so much time and can’t be perpetually available, Miku is software that anyone can buy and use. It only costs $200 and doesn’t require particularly advanced technical skills. Most of the people who produce Miku music are self-taught. One of the enduringly popular things about the concerts is that everything you see essentially comes from fans – the music, costuming and dance routines are all drawn from the expansive ‘Miku community’, where the lines between amateur and professional are deliberately blurred by everyone involved. You’re as likely to hear a song produced through a record label as you are one that was popularised by YouTube.

Creative industry

In the 1990s the term ‘cultural economy’ brought a double meaning to creative work. First, it captured the cultural dimensions of economic activity, like packaging design or marketing, and gave them an artistic dimension. Second, it referred to an expanding category of economic activity concerned with cultural goods and undertakings centred around value and profits. It would see the ascendancy of creatives to the C-suite, where companies across a range of industries appointed chief creative officers (CCOs) to oversee ‘creative activities’ and align them to corporate strategies and visions. Scan through job descriptions and you’ll see that CCOs are expected to be strategic leaders and ‘igniters’ of creative intuition within organisations. CCOs are charged with finding more ‘creative solutions’ to problems that often stretch beyond an organisation’s core operations.

Hidden tracks

Young and Kucyk are as good at tracking down hard-to-find people as they are at tracking down hard-to-find music, although sometimes they do reach dead ends. Their methods aren’t particularly advanced and are often helped by luck. Sometimes they’ll raid the White Pages. Sometimes they’ll search for relatives of musicians online. Sometimes – as in the case of another song on Someone Like Me – they’ll scour through five years’ worth of archived weekly newsletters from a Seventh Day Adventist Church in the UK and Ireland and spot a tiny article that contains the full name of a mysterious musician they’re trying to find.

No secret passageway

In 2001 I read an article in The Guardian newspaper about a man who fell from the sky, landing in a superstore car park not far from where I live in London. The article, by journalists Esther Addley and Rory McCarthy, detailed how the Metropolitan Police discovered the dead man’s identity through a combination of luck, Interpol and British-Pakistani community workers. Muhammad Ayaz had managed to slip through security at Bahrain airport, run across the tarmac and, according to witnesses on the plane, disappear beneath the wing of the British Airways Boeing 777. The article quotes a spokesman from the International Air Transport Association: a myth circulates that there is a ‘secret hatch from the wheel bay into the cargo bay, and then into the passenger cabin, as if it were a castle with a dungeon and a series of secret passageways’. No such passageway exists and Muhammad would have found himself trapped in the wheel bay with no oxygen, no heating and no air pressure as well as no way out. If he wasn’t crushed or burned by the retracting wheels, he may have frozen to death once the flight reached 30,000 feet, finally falling out hours later when the plane lowered its landing gear as it prepared to touch down at Heathrow.

Home is where the haunt is

Ghosts, like people, tend to be attached to a particular place. The term ‘to haunt’ in English has three linked meanings. First, for a ghost to manifest itself at a place regularly: a grey lady who haunts the chapel. Second, to be persistently and disturbingly present in someone’s mind: the sight haunted me for years. Third, to frequent a place often and repeatedly: that’s his old haunt. Home and haunting go hand in hand. Ghosts don’t haunt an entire city. They haunt a specific house, a dwelling, usually assumed to be the place where they died.

Interstitial

American sociologists John and Ruth Hill Useem first coined the term ‘third culture kid’ in the 1950s to describe the experience of Americans who were raised abroad in a culture different to their birth culture. This term reflects the way children raised overseas straddle three cultures: the culture of their birth, the culture within which they are raised, and a third, nebulous culture – the culture they create through the way they learn to relate to each other. The third culture is interstitial, not an amalgam. ‘Third culture kid’ (TCK) is a term often used as shorthand. Many TCKs will have experienced more than one cultural shift too. Those with diplomatic, military or missionary families are often raised in multiple countries, and others, like me, will continue their travels overseas as adults too, exercising the global and economic mobility they know well.