Featured in

- Published 20231107

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-89-4

- Extent: 208pp

- Paperback, ePub, PDF, Kindle compatible

AS I WRITE this, my dogs are curled up in the sun on the bench beside me. It’s winter in Brisbane, bright and cool, and the smaller of the two, Quito, is wearing a cable-knit jumper, startlingly pink like fairy floss. It has a turtleneck of sorts, and little holes for his front legs, and when I put it on him, it triggers a ‘cozy’ reaction, and he instantly runs to the nearest fluffy location and snuggles in. Today, he’s chosen a thick, round pillow on top of the thinner cushion topping the bench. The larger of my two dogs, Tukee, can’t seem to move when he’s got a jumper on, so he’s using Quito as a hot water bottle. I don’t blame him. I can’t quite feel the tips of my fingers, all too naked, as I type.

My husband is overseas, my daughter back at school. In the temporary quiet, I’m thinking about my father, who died not so long ago, and about my mother and sister, who are adjusting to a new, closer way of living, 13,000 kilometres away from here. I could text them, or FaceTime, or scroll through a social feed – but I find it hard to feel connected over such a distance. I am too conscious of my own small face in the corner of the screen, the garble of my comments online. I am not quite my real self.

We’re social animals, humans – from the wiring of our brains to the shape of our societies. If recent pandemic lockdowns taught us one thing, it’s that we need to be physically close to each other, to socialise not just as avatars or gigabits but as live, warm, fallible bodies. Our dogs knew this ages ago. Have you ever tried to say hi to your dogs over Zoom? Most of the time when I try, they don’t even acknowledge my voice. I’m an in-person person, and they are, too.

Every now and then, our resident juvenile brush turkey, who we call Dr Alan Grant, comes to the sliding-glass doors begging for pieces of apple, and when she does, the dogs leap up to defend the house. It’s a fair call, actually – Dr Grant would very much love to be inside, as she was once, accidentally. She got a taste for it in those forty seconds: the big grey couch, the bookshelves, Netflix. This is where all apples come from.

But this isn’t a story about Dr Alan Grant – it’s a story about my dogs, and all our dogs, and what they tell us about our own humanity. How, tens of thousands of years ago in a half-frozen world, humans invited wolves into their family circles and domesticated them, and in doing so made sure that today we never really have to be alone, even when the internet drops out.

THE PLEISTOCENE WAS cold, made colder by a mis-tilt of the Earth 115,000 years ago that caused ice to form across what is now Canada, the US and Europe. Where there wasn’t ice, the Northern Hemisphere was predominantly wide, grassy plains on which giant species evolved – mammoths and mastodons, sabre-toothed cats, one-tonne ground sloths, dire wolves. By the time the Ice Age hit, modern humans, Homo sapiens, had been evolving in Africa for 150,000 years; some of these humans moved not away from the ice but into it. By the time the Ice Age ended, more than 100,000 years after it began, humans had colonised not only Europe and Asia but Australasia and the Americas, and they took dogs with them.

Grey wolves in the Pleistocene, unlike their larger dire cousins, were around the same size as grey wolves now – and for most of our shared history, humans and wolves have lived as competitors, each a threat to the other’s survival. But in some ways, our two species were made to connect. Both are intensely social, live in family groups and communicate using a wide range of facial, bodily and vocal signals, often subtle; we reconcile after fights, play as adults and use touch to build and maintain social bonds. Wolves use sounds, postures and expressions to reinforce group dynamics, including dominance or submission, and to express pleasure, warn intruders away or rally others. Like humans, they have an acute social awareness that enables them to communicate their own intentions effectively, understand the intentions of others and modify their behaviour appropriately in response.

Precisely how, when and where dogs were domesticated remains a mystery, but recent DNA studies suggest that at some stage, as long as 40,000 years ago, humans in north-eastern Siberia, as well as possibly eastern or central Eurasia, began to accept wolves into their social groups. So began the first domestication of an animal species, the grey wolf. At first this process was unconscious – a tenuous social alliance – but eventually humans bred the animals for their speed or fur or other desired traits, producing the 360-plus dog breeds we know and love today.

WE DIDN’T PLAN, at the start, to become chihuahua people. In March 2018, my daughter and I ambushed my husband while he was on a work trip in Brazil. He’d been out with colleagues, came home late and was a little tipsy, and in that state it was easy to convince him over the phone that we needed a second dog.

Our family dog, Lupa, was then thirteen, and a somewhat old thirteen at that, due to a longstanding metabolic issue. Lupa was a rescue, discovered by our friend during creek restoration on Brisbane’s north side, and she was on the independent, quiet end of the Jack Russell/fox terrier spectrum – a pottering great-aunt sort of dog from an early age. She was affectionate in a reserved way and indiscriminate in that affection. Her tail never stopped wagging.

But Lupa needed a sibling. She was slowing down, and a puppy would liven her, we argued, keep her from being bored. We were crafty and compelling. A few days after Robbie returned from overseas, we went to meet a litter of puppies.

Whippets are among the most mild-mannered of all dog breeds – as adults, anyway. The whippet puppies were plump and sleek like fish, and boisterous, and as we tugged ropes and threw plastic bottles for them, the adults, refined and languorous, watched on like marble gods. But our small townhouse, small garden would not fit this kind of art – and we felt that we needed a dog that was shorter than Lupa, and lighter – someone she could boss around if she needed to. A bigger dog, we worried, would be hard for her to handle.

So, we got a chihuahua.

We knew very little about chihuahuas at the beginning, aside from what the American Kennel Club website told us: ‘A graceful, alert, swift-moving compact little dog with saucy expression’ and ‘attitudes of self-importance, confidence, self-reliance.’

And what our friends said, without words, when they raised their eyebrows at us.

DOMESTICATION IS A long, messy process, involving many generations of animals who are selected and bred for particular features. We can see in our various dog breeds today what some of these traits might have been: protection, hunting, warmth, companionship. In 1959, Russian biologist Dmitri Belyaev began a groundbreaking experiment with foxes to demonstrate how the domestication of wolves to dogs might have occurred, based only on variation in behaviour among individual animals.

Foxes coexisted with wolves and humans in the Pleistocene, but because they are smaller and more solitary, they were more likely to be eaten than tamed. Yet these same characteristics made them ideal for scientific study. Many generations of foxes could be easily and quickly raised and bred in captivity – and, in fact, they already were. Belyaev began his experiments using foxes reared commercially for their fur, which were as aggressive and averse to humans as any wild fox would be. However, there remained some variation in the aggressiveness or docility of individual foxes. The scientists selected the most tame or docile individuals in each annual litter and bred them with each other – then bred the most docile of those pups with each other, and so on. Researchers developed relationships with the foxes, cuddling and feeding them. By the fourth generation/year, some fox pups were wagging their tails when humans approached them, as dogs do; by the sixth generation/year, around 2 per cent of the fox pups not only wagged their tails when humans arrived, but whined when humans left, whimpered and licked their human carers, and chose to be around people. By the thirtieth generation, almost half the fox pups behaved this way.

Although the scientists selected animals for their temperament, the foxes’ physiology and bodies also evolved. In only fifteen generations, the domesticated foxes’ stress hormones were half the levels of their wild counterparts, and more recent research has shown key changes in serotonin metabolism in the brains of domesticated foxes, in ways likely to improve mood stability and ‘happiness’. Domesticated foxes developed bicolour faces like border collies or white star markings on their heads, curly tails or floppy ears. Overall, their faces became more juvenilised – simply said, as they were domesticated, the foxes became cuter.

I WAS DRAWN to Tukee from his online photo, blurry as it was, and tried to go and meet him with an open mind. He had lived on a farm for his first six months, and when his owner let him out of the house he sprinted around all the sheep in the front garden, stopping and starting, playing his own strange game as if to charm us. He had a thick, off-white mane around his neck and chest that, against the shorter blond of his coat, seemed like a ruffled shirt, a nod to royal or rockstar tastes. He was interesting and unpredictable in the right sort of way: it was love at first sight.

We brought Lupa out from the car, and she completely ignored him.

Tukee immediately accepted us as his people, including Lupa, whom he tracked as she moved among patches of sun. Lupa spent much of her life stretched out toasting luxuriously, solitarily, on the floor, stairs or deck. Tukee spent much of that first year cuddling her as she did so. She didn’t love it, but he more than compensated by teaching her to bark again. Lupa, almost deaf for two years, had stopped telling us when she was hungry or when the possums were out. When he was hungry and being ignored, Tukee learnt that he could yap in a high-pitched tone that Lupa could hear, and elicit loud, annoying barks from her that we responded to. Lupa got her bark back.

When Lupa died eighteen months later, I held my hand against her head as her eyes went empty; I needed to touch her as she left as I had touched her in her living. We had a family memorial for her; I eulogised her online. Tukee stopped eating.

IN LATE 2021, my father’s cancer advanced suddenly, and after a few weeks in ICU he was brought home in an ambulance to finish dying in the living room of my childhood home in Iowa. The hospital bed was erected between the two lounges, facing the small television and the clock on the wall. That coming-home day was the best day he had in all the days I saw him before he was gone – he was home, with his people. He couldn’t stop smiling.

I have failed again and again to write about those weeks, as he became less of his mind and more of his body, as I shifted his bony frame from side to side, cleaned his mouth, chest, anus. I thought there was time to revisit the family history, the stories I’d forgotten, but it was already too late. He was so tired, dying, and my mother, warm and alive, curled up in her chair and ached. I have tried to understand what those three months meant, more than just everything. On the day he arrived home, I posted a picture of the ambulance on Instagram, captioned ‘Dad’s home! ❤⭐’, as if that captured even a fraction of what I wanted, or needed, to say:

We die, we are dying, there is hope, I’m alive, I can do this. How will I do this?

I needed to share the experience with other humans; I needed to connect. But it came out all wrong, too artificial, unconsidered – a snapshot when I needed an essay. From all over the world, my friends, people who loved me or understood what this time was, responded with kind words, love hearts. I sat alone on the couch, apart from my virtual self.

HUMANS PROBABLY BROUGHT dogs with them when they migrated across the frozen Bering Strait from Siberia into the Americas 15,000 to 33,000 years ago. Prior to that migration, there were no humans in the Americas; there were wolves and coyotes, but – without our early influence – they did not evolve into dogs. When the Bering Ice Bridge melted at the end of the Ice Age, humans and dogs in the Americas were isolated from the rest of the world for at least 9,000 years, until the Europeans arrived in the late 1400s and early 1500s.

In seasonally colder regions of North America, Indigenous peoples kept larger, husky-like dogs that improved hunting success or produced warm, woolly fur. Further south, in what would later become Mexico, the Colima, Maya and later Toltec and Aztec peoples bred small mute (techichi) or hairless (xoloitzcuintli) dogs, which were sometimes used as food and were buried with people to guide them to the afterlife. For a long time, it was thought that the Aztecs’ small dogs were lost when they bred extensively with European dogs after colonisation. But descendants of the techichi were rediscovered in the 1800s in the Mexican state of Chihuahua, and quickly became popular internationally.

Today, only a few American breeds still show evidence of their pre-colonial ancestry: the modern, still-hairless xoloitzcuintli retains 3 per cent of its ancient DNA and the techichi persists as 4 per cent of the Mexican chihuahua, no longer even remotely mute.

QUITO CAME INTO our lives in part to help Tukee through the grieving process. He is two years younger and significantly smaller, almost half the size. He’s what they call a tricolour, mostly black but with ruddy eyebrows and a white crest on his chest like a superhero. He loves being carried, gets the hiccups, is shy. He barks or growls at the postie, at the crows and, on occasion, at Tukee when he tries to cuddle him, and when he barks his hackles rise – making him look, suddenly, like a tiny black wolf.

Quito is a simple creature, motivated more by food and temperature than affection. He is shaped like a piglet and gulps his kibble so quickly and voraciously that his farts are horrific. We’ve invested in every kind of bowl, mat and puzzle game you can imagine to slow him down. If we were all trapped together somewhere, and food was on the outside, he’d adeptly catch flies for us to survive on – or he’d eat us, guiltily, until he exploded.

As far as we know, our dogs are entirely unrelated to each other, yet they behave as siblings – older and younger – and we find ourselves treating them that way, too. Quito gets concessions for being the baby; we expect more from Tukee as elder. Several times a day, they play and they fight, and I think of my little sister, our long-ago games with her Lego, He-Man and Orko, my Barbies hidden in her closet.

ON INSTAGRAM, YOU’LL find more than thirty-five million images tagged #chihuahua. Among them are chihuahuas in prams or wearing cute outfits or wagging their tails so hard they might just take wing – but all of them feature a small dog with slightly bulgy eyes and ears like ship sails. For all the diversity among individual chihuahuas, there is still an energy that connects them, that connects us as their owners across more than a thousand years.

In fact, google ‘colima dog’ and you’ll see the same dogs as crafted by artists in pre-Colombian Mexico, ranging between 2,200 and 1,400 years old. In the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, a forty-two-centimetre ceramic colima dog vessel lies on its belly, grasps a corn cob between its forepaws and gnaws it, pointed ears up, tail up, hind legs extended behind like chicken thighs. The clay is blond, smooth with age. Give Tukee a stick, and this is how he chews it.

At Mexico’s National Museum of Anthropology, a palm-sized red-clay dog barks or snarls – ears alert, tail curled over his back, belly round. Quito’s belly is the same, despite the care I take with his food, because it’s his shape: his torso is short, his ribcage broad, and he will always look delicious.

You will see ‘Reclining Dog’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the colour of a burnt-sienna crayon, lying attentively, as though his master has asked him to. His forearm wrists are curled in together at the front, in that way that seems so uncomfortable when my own dogs do it, which is when they’re most relaxed.

And my favourite, also at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico, which is not the most beautiful but simply speaks the loudest: a small ceramic dog wearing a human mask, with dark brows and hawkish nose. The clay is red, shiny – mottled with black, like age spots. According to experts, the mask signifies that this colima dog was supernatural. But to me, the mask says something else, too – about our long history with these animals, and the relationships we have developed with them.

HERE IS HOW you meet my dogs:

When you arrive, there will be barking. Do not make eye contact; do not make abrupt movements or gestures; do not try to pet them or acknowledge them in any way; do not push them away when they sniff your legs, groin and face assertively. Sit down, and they will need to start again. Stand up, and they will need to start again. Go to the bathroom, emerge (to them) as a completely new person, and start again.

After a year or more of meeting you repeatedly, they will recognise you as part of our extended pack, as family. Then, everything changes. You arrive, and when you have at last patted them hello, they will tremble, kiss you profusely, and you will have warm cuddles in your lap, your arms, over your shoulders whenever you might like a silky rush of oxytocin – when you don’t even know that you need it. There is something very special about cuddling an animal the size of a baby human when there are no baby humans around.

I CAN’T YET define the gap my dad left – it’s more than his life, our L-shaped house, the fruit trees he planted, the habit he had of collecting. More than my memories of forty-six years, what decades of photographs say, his voice on my sister’s phone, his words in her inbox. I don’t want to worry I wasn’t enough. What matters most were not the words or the images, but the hugs, the hands, how he carried me on his shoulders, how I tried to hold him up when he fell.

I came home to Brisbane from those last months in Iowa, winter to summer, stepped out of the car and through the gate, and my dogs were there. I needed them first, the squeals and spins, how they paw the air like circus horses, how they kiss without humility or restraint, how they wear their small anxious wolf-pack hearts on their sleeves, as I do, as it pains me to do. My chihuahuas remind me that we’re not all one thing, that we’re vulnerable, reactive; we need each other.

HUMANS ARE ALWAYS reading the minds of other humans. We are sensitive to countless overt and subtle cues – body language, vocal tones, facial expressions – and we use these to predict other people’s thoughts or emotions and to adjust our own behaviour accordingly. We draw on these same abilities when we read or tell stories. We use written cues to transport into fictional characters’ bodies, and we understand even as young children how to read an audience and respond in ways that keep people listening. Humans evolved the means to both embody others and respond to others’ bodies, but did so before letters or phones or computers, when we still lived in small family groups. Before likes and emojis, re-shares and hashtags, we were in-person people, all of us.

Our dogs perceive our feelings and understand our gestures better even than our nearest relatives – the apes – do. Wolves avoid eye contact, as it’s a sign of aggression, but even as puppies, dogs focus on human faces, seek out our gaze. My dogs don’t care what words I choose online, who I seem to be on Facebook. They understand their names, ‘bedtime’, ‘dinner’, ‘upstairs’ and ‘inside’; beyond that, what I say doesn’t matter – it’s the tone of my voice, the tension in my body, and what I do that counts.

I point, and they look past the end of my finger; I look at them, and they know who I am.

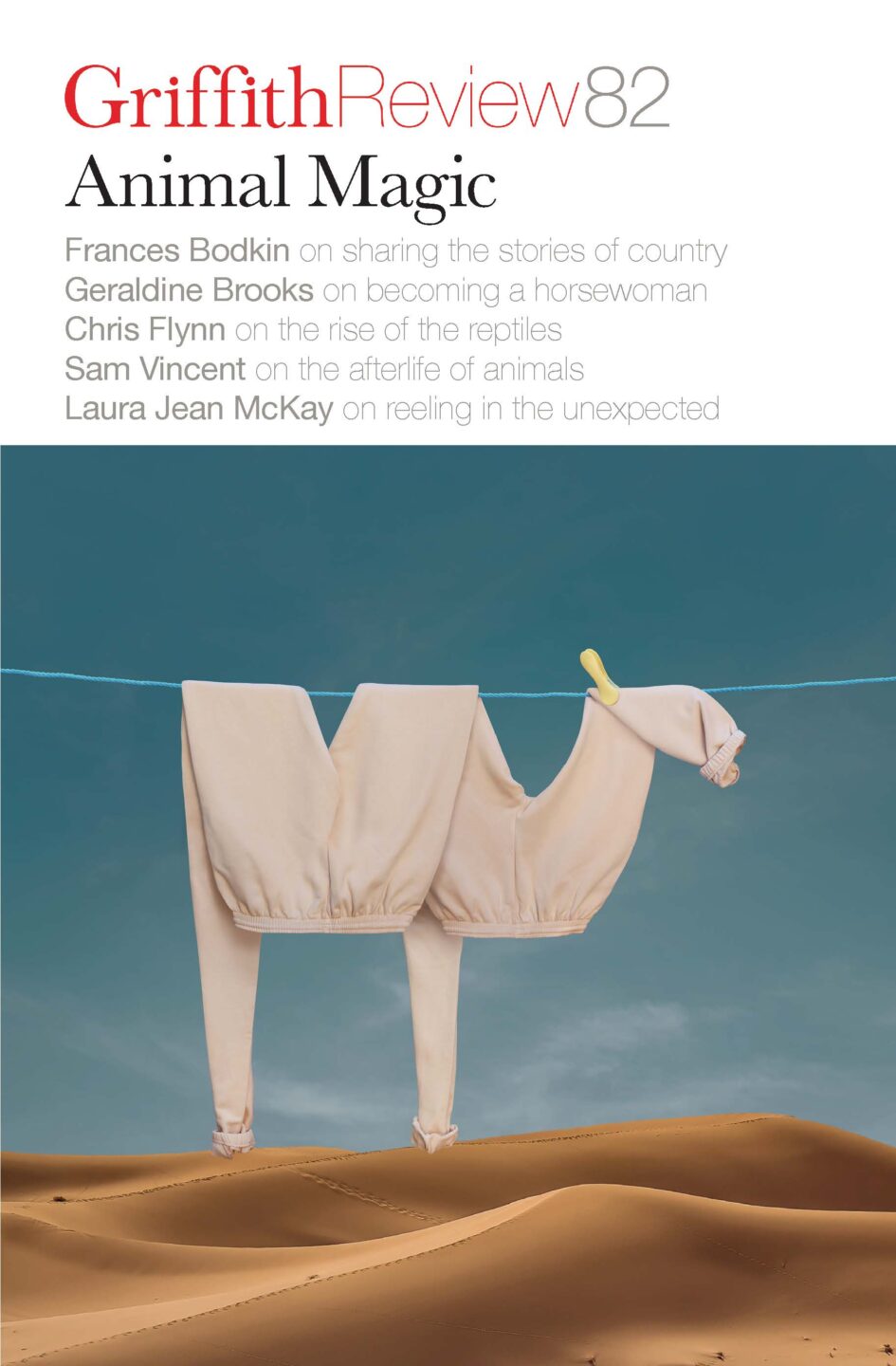

Image credit: Getty Images

Share article

More from author

Steering upriver

Non-fictionAt dawn I cross the bridge, Missouri to Iowa, and turn down the gravel drive. Though I’m different now, this place is the same as it always is this time of year: the sun glowing red over the paddock next door, the grass not yet green, the maple stark. I go away, come back again, and home is like a photograph where time winds back, slows into stasis; where the carpet has changed, but the dishes have not, the cookbooks have not, the piano and artwork and bath towels have not. Here, I can be a child again, my best self, briefly. I hold on to this moment for as long as I can, because too soon I’ll remember how disobedient I am, how bossy and domineering, how I slammed my door until Dad took it off its hinges, how soap tastes in my mouth, how I pushed on these walls until they subsided.

More from this edition

Where the wild things aren’t

Non-fictionMelbourne Zoo knows that it sits in an uneasy position as a conservationist advocate, still keeping animals in cages, and with an exploitative and cruel past. Our guides for the evening walked a practised line between acknowledging the zoo’s harmful history and championing its animal welfare programs, from the native endangered species they’re saving to their Marine Response Unit, a dedicated seaside taskforce just waiting for their sentimental action movie.

When the birds scream

Non-fictionI read books in which girls like me made friends with cockatoos and galahs, and my mum told me stories about my pop in Queensland who could teach any bird to speak and to whistle his favourite country songs. My favourite story was the one about the bird who used to sit on his shoulder while he drove trucks for work.

Into the void

Non-fictionI think with a little fear, as I often do, of the many other (and much larger) creatures whose natural territory this is, and scan the surrounding water for any dark, fast-moving shadows. But soon I relax and settle into the rhythm of my freestyle stroke. Breathe. Pull. Pull. Pull. Breathe. Pull. Pull. Pull. Breathe.