Featured in

- Published 20231107

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-89-4

- Extent: 208pp

- Paperback, ePub, PDF, Kindle compatible

READER, I’VE TRIED. I’ve tried so hard not to begin this introduction by writing about my cats. But here I am, writing about my cats. I can’t stop myself.

They’re both rescues. My partner and I picked one each from Brisbane’s RSPCA shelter nearly four years ago: I chose Nancy (now eleven years old, tortoiseshell, confident); my partner chose Emmett (now five-and-a-half years old, fluffy, confused). Both cats go by many other names – Nancy’s aliases include Inspector Kopanski and Nancy Pawlosi, Squeaker of the House; Emmett is sometimes Mr Bumblypants or Sir Fluffalot. These monikers, obviously, say far more about my partner and me than they do about our cats.

I sometimes wish I could ask Nancy and Emmett what their lives were like before they came to live with us – if they were other people’s pets before they became ours, or if they were on the lam, hiding behind skips and learning survival skills such as how to unwrap a kebab (a talent possessed by my partner’s previous cat, Charlie). I usually conclude that it’s better not to know, and that the language we do share – the gestures and noises and facial expressions – tells me enough about them to make up for the mysteries of their past.

I suppose this imperfect communication is part of why we human animals find our non-human counterparts so beguiling, why they sometimes seem to possess magical or otherworldly qualities. We never quite know what they’re thinking, despite our best attempts to understand them. And the more they differ from us – if they’re winged or scaled or six-legged or breathe through a set of gills – the more removed we’re likely to feel from their experience of the world and their right to exist within it.

Animals still outnumber humans, despite our best efforts (we represent just 0.01 per cent of all life on Earth). And while they could live happily without us – our cruelty, our destruction, our ridiculous nicknames – we simply couldn’t survive without them.

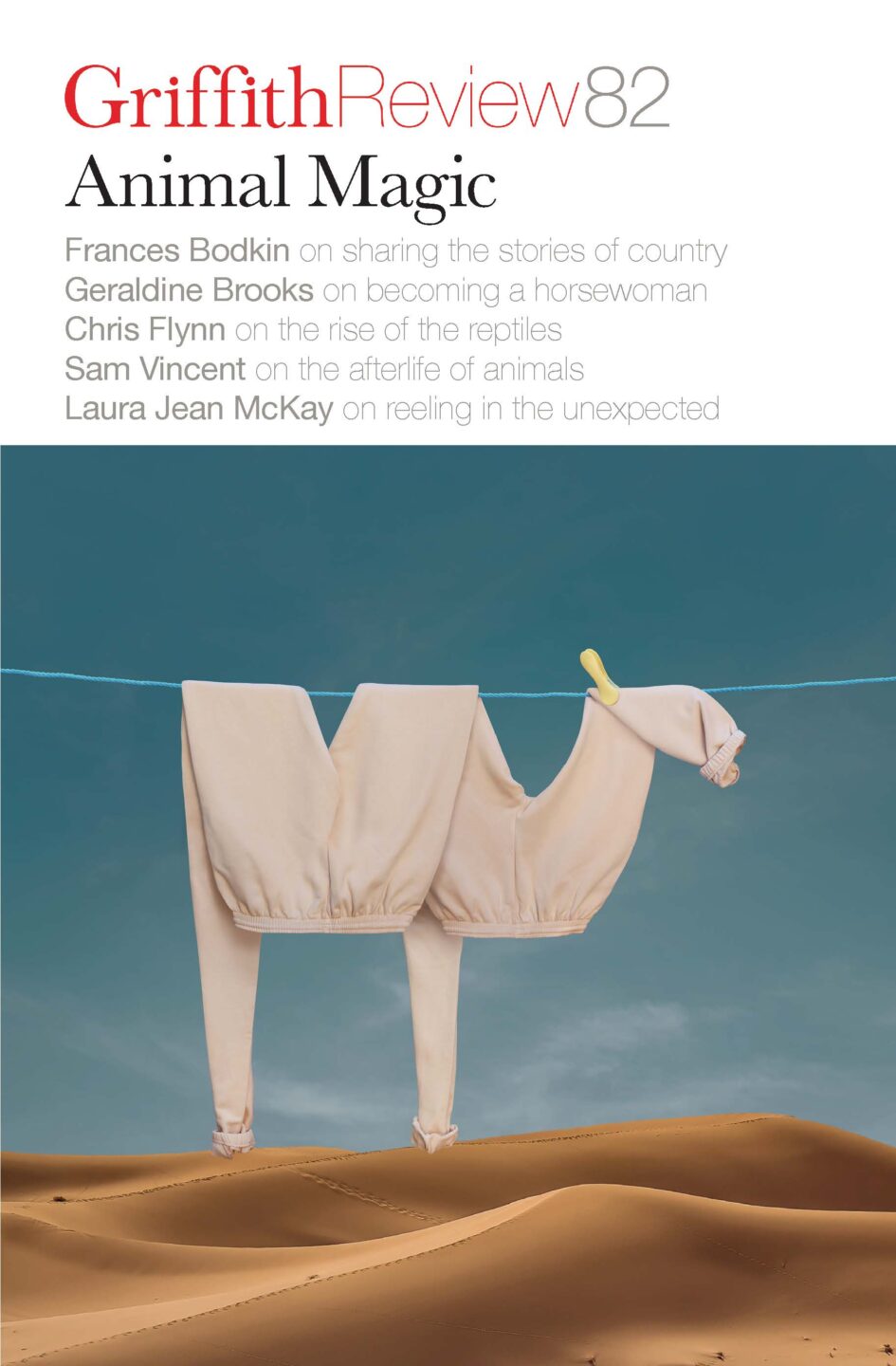

THIS EDITION OF Griffith Review illuminates the magic and mystery of animals – those we’re lucky enough to still share the planet with, and those, like dodos and dinosaurs, who are no longer here. It celebrates the complex bonds we have with all kinds of other creatures and reminds us what’s at stake for their – and our – survival, thanks to the widespread environmental impacts of humanity’s presence. The stories in this collection explore animals in life and in death, in the sea and in the soil, in the zoo and in the museum, in literature and film, in our imaginations and our memories and our homes.

(I should tell you now that there isn’t a piece about my cats, but if you’d like to know more about them I’m always ready with an anecdote and a series of supporting photos.)

Thanks, as always, to the wonderful Griffith Review team for their unfailing hard work, excellent ideas and good humour. And thanks to Nancy and Emmett for coming to live with me and choosing to stay.

8 September 2023

Image supplied by Nancy and Emmett

Share article

More from author

Subject, object

The vivid hues and spiky leaves of Jason Moad’s Temple of Venus – the arresting artwork featured on the cover of Griffith Review 89: Here Be Monsters – raises a tantalisingly sinister proposition. The subject of the painting is clear – a Venus flytrap, realistically rendered – but there’s a somewhat otherworldly quality to this plant, a sense that it might be biding its time, waiting to strike while we, the viewers, are distracted by its beauty. For Melbourne-based realist painter Jason Moad, this slippage between subject and object, reality and imagination, is part of the point.

More from this edition

Sartre’s lobsters

Non-fictionIn The Secret Life of Lobsters (2004), Trevor Corson describes how, before the lobster’s status had sufficiently improved for affluent urbanites to desire its meat, ‘lobster’ was used derogatorily to describe British redcoats during the American Revolution and, later, dupes or fools in general. Which brings me to Jordan Peterson.

Narratives of the natural world

In ConversationAll kinds of interpretation are a form of fiction. These are fictions that we need in order to connect with the larger environment. When our current thinking has failed to make us think of ways to connect with the environment, art may be the only way we can have access to new ways to think about where we are in relation to the environment.

metanoia

Poetry the book holds the horse – rustling in there, taking pages between lips, rubbing upper lip across them, nostrils twin jets of air as it seeks sweetness maybe...