Featured in

- Published 20210202

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-56-6

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Click here to listen to Editor Ashley Hay read her introduction ‘Create, destroy, reset’.

WE’RE TERRAFORMING, MY son and me. We’ve done this in the real world before, tree by tree – but this time, it’s virtual, pixelated. Digging down and piling up, creating landscapes and buildings and ponds. I place green blocks of grassy stuff slowly, one by one. My son deals his out like a top-table croupier.

‘So how much of this stuff do I have?’ I ask. Another block. Another cube.

‘As much as you want, Mum.’

‘There’s no limit to the resources I can use?’

‘Nothing runs out.’

Grass. Wood. Stone. Fish. Food. Water. Glass. Gems. Tools. Another crop. Another building. Another panda. Another cow. Nothing is earned or purchased: it’s all just there to use. And there’s a curious satisfaction in laying down piece after piece of green, brown, blue without having to think about shortage – or consequence.

This seductive bounteousness: as much as you want.

Minecraft, for those who don’t live with a twelve-year-old, can be played in two modes: creative and survival. There are internal games, variations and opportunities, but it’s fundamentally a world-building app, like Lego on-screen, allowing the construction, block by block, of everything from basic to elaborate topographies, residences, lands. I painstakingly complete my row of grass. My son spawns llamas, chickens and pandas, and plants more corn – this profligate abundance. He dumps bucket after bucket of never-ending water into a new pool for more dolphins, turtles, sharks and more of Minecraft’s 3,584 different kinds of available tropical fish.

The problem is, of course, this is not how most real-world resources work.

THE INELASTIC LIMITS of the planet and just about everything it holds are well documented. There’s even an Earth Overshoot Day, when the world’s population exhausts the resources the planet makes available for each calendar year. As Lesley Hughes writes in this edition, that day has crept forward year on year – from late December in the early 1970s to, in 2019, its earliest ever: 29 July. (Measured as a single country, Australia used up its load months earlier, in March.) Overshoot Day had its own moment of Covid-pause, delayed until 22 August in 2020, as global consumption eased. Welcome respite, the Global Footprint Network noted, but one that would ideally have been achieved by ‘design, not disaster’.

Those regained three and a half weeks spoke to many questions sparked by the pandemic. Would resources – and humanity’s relationship to them – be impacted by the virus, by its potential rupture? Would the value or importance of intangible resources become as important, more important, than more tangible ones? Would expectations of quantity, agency, access and control be changed by the unexpected lives many people lived last year? Would responses to Covid inform responses to other immense planetary threats – loss of biodiversity, the arrival of the Anthropocene, the escalating impacts of climate change?

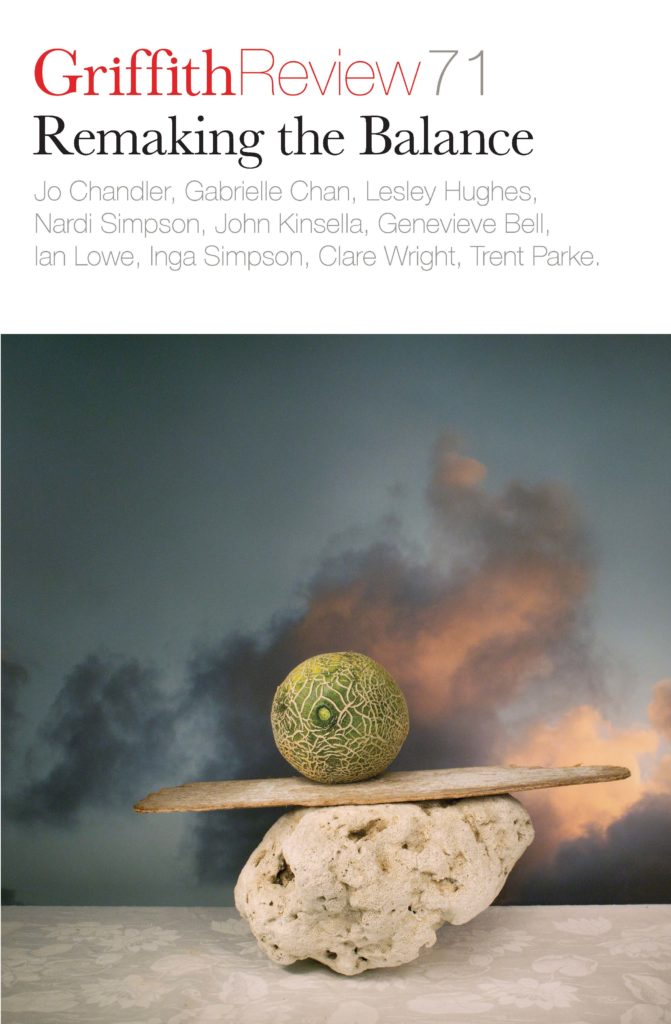

ASSEMBLING AN EDITION of Griffith Review is a bit like world-building in Minecraft, placing one block next to another and seeing greater shapes and possibilities emerge in their combination. In this edition’s explorations of resource and new balance, the climate crisis looms large: Jo Chandler and Sophie Cunningham both write in this context of exercising courage and hope as if they were muscles, which feels like a critical prescription. Ideas of supply, demand and value play out across landscapes, from Gabrielle Chan’s wide fields of agricultural policy to Matthew Evans’ microcosms of soil. They resonate through Elspeth Probyn’s celebration of small things – fish and snails – and Robin Roberts’ celebration of the quintessential summer fruit, the mango. They intersect in Alan Schwartz’s late-onset political awakening as an active capitalist, and Julian Meyrick’s epiphany about ‘value’ beyond the ideas of economic analysis. Bronwyn Fredericks and Abraham Bradfield lay notions of inner-city bounty – even in the wake of supermarket limits exposed by last year’s toilet-paper rushes – alongside the enforced and expensive precarity of basic provisions for many Indigenous Australians. Ian Lowe, Nicole Hasham and Clare Wright explore potential energies from the future and the past. And Barbara Kingsolver’s poetry provides ‘how-to’ guides to lay beside Katie Holmes’ projections of collective memory, and of narrative itself as a resource.

The capacity to tell stories – whether they reframe the past or forecast the future – is a signal resource allocated to humans. On this continent, alongside storytelling, there exists a particular tradition of trade, a literal gift in the landscape. In this collection, it manifests as an extraordinary invitation extended by Yuwaalaraay writer, musician, composer and educator Nardi Simpson to enter a more generous and rewarding process of exchange, lifting the idea of resource, of asset, of object, out of time and materiality, beyond narrow expectations of numbers or returns. This powerful and lyrical journey is the first work developed under the auspices of ‘Unsettling the status quo’, a commissioning-editor mentorship undertaken with Griffith Review by Grace Lucas-Pennington from black&write!, thanks to the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

And even Minecraft has its limits. One enthusiastic player – who has delineated the boundaries of the game’s world at 921 quadrillion blocks – estimates that if 7.5 billion people played in a single Minecraft world at once, it would take four years and five months to deplete its first resource: gold ore. To get 7.5 billion people to play Minecraft together at the same time would take an unprecedented act of global collaboration – which might be more usefully directed elsewhere. Then again, perhaps it’s as good a start as any. Choosing between creative and survival has a different resonance these days.

Another resource available to those 7.5 billion players is imagination. Even if overthinking mothers of a certain age find the value of games like Minecraft suspect, those billions of players would be in there, thinking, making, creating, for all that time.

The Global Footprint Network is currently calculating Overshoot Days for 2021, country by country. At the time of writing, its ‘now-cast’ system predicts that Qatar will exhaust its years’-worth first on 9 February, followed six days later by Luxembourg. Indonesia will last until 18 December, while the two-island nation of São Tomé and Príncipe will live most within its means, only exceeding its annual resource quota on 27 December. That’s still four days short of any semblance of balance.

Our relationships with resources are defined by what we do with all that’s animal, vegetable and mineral in the world – as well as with so many less tangible commodities. The challenge now is how to reach for new sustainabilities; how to change what we do with what we have, be that snails or sunshine, soil or stories.

30 November 2020

Share article

More from author

Between different worlds

IntroductionAntarctica offers windows into many different worlds...

More from this edition

A long half-life

EssayON MY DESK there sits a well-thumbed copy of the 1976 Fox Report, the first report of the Ranger Uranium Environmental Inquiry. I grew up...

‘A poem is a unicycle’

InterviewIN LATE 2020, Barbara Kingsolver published How to Fly (In Ten Thousand Easy Lessons), her first poetry collection in almost twenty years. Many of...

urgent biophilia

Poetrywrist-deep in dirt for something less particular satisfaction more tasty than butter lettuce wilting kale curling towards sun cabbage grubs chew chew chewing cabbage butterflies pupating try a decoy moth mobile the...