The geography of respect

Rock climbers, Traditional Owners and reconciling ways of seeing

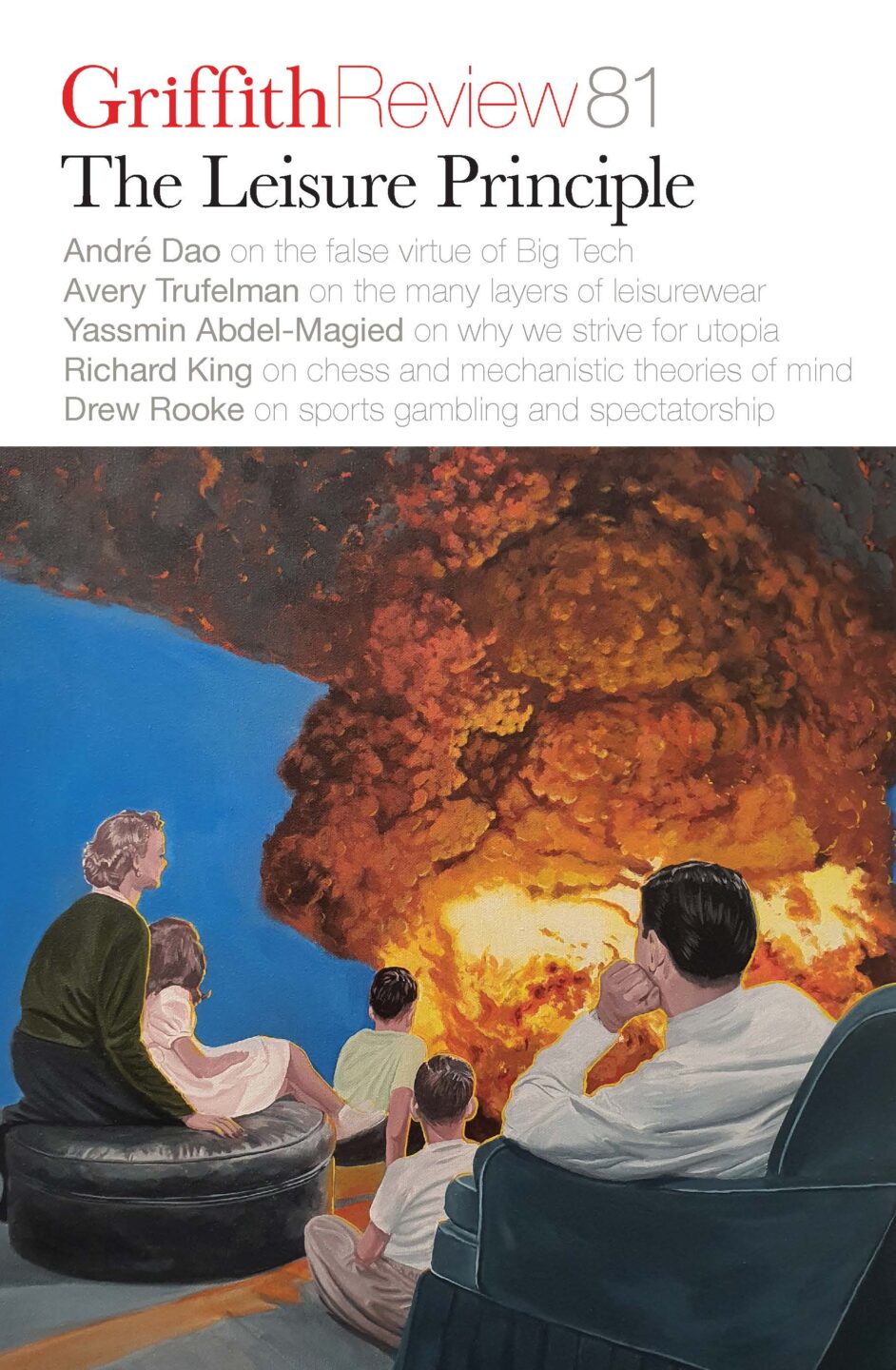

Featured in

- Published 20230801

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-86-3

- Extent: 200pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

Healthcare is other people

‘I see a lot of junior doctors suspend what I think of as their natural self during training,’ Bravery tells me – the self that is patient-centred and came to the profession because they wanted to help people. ‘They think that once they get far enough along the training pathway then their natural self will just come rushing back. But often it doesn’t.’ With this observation, Bravery identifies what is known in the broader education context as the ‘hidden curriculum’, the unwritten and untaught – and generally negative – behaviours that we see in those around us and learn to emulate to assimilate and excel. In the medical context this usually means a retreat from patient-centredness, a harried and sometimes imperious air, and a concern for money and distinction. Medical students are told about patient-centred care… We labour over weekly theoretical case studies during our pre-clinical (that is, classroom) years to the constant refrain from tutors to think of the patient’s experience and social circumstances.

More from this edition

Lying on grass

FictionJamie wishes he could be more like Todd. Not because Todd’s excellent, but because he figures out what he wants and does it. As they pull out bits and pieces from the skip to build their drum sets, Jamie thinks about how he wants to be free, but doesn’t know if that’s something a person can ‘do’. After a while they’ve constructed two sets side by side at the front of the driveway. They’re not buckets, tins or lids: they’re tom drums, snare drums and cymbals.

Sonnet for the weekend

Poetry Glory to God for long weekends,for lattes served by obsequious baristas,sunnied eggs and bacon with the crispy ends,for an empty park in front of...

Stories from the city

In ConversationPublic art in particular is a great way for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to tell different histories and narratives that are site specific. There are lots of hidden histories that we know as community but that lots of other people don’t, and so we use these public spaces as opportunities to install different types of artwork to allow people to engage with these histories and stories during their everyday commute...