Featured in

- Published 20221101

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-74-0

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

WHEN I TELL people that I wrote my PhD thesis on cookbooks, they usually react in one of two ways: excited or mystified. I’m not about to launch into one of those meaningless ‘there are two types of people in the world’ aphorisms – honestly, after four years of examining cookbooks through an academic lens, even I was experiencing diminished excitement returns. But one doctorate and a decade later, I’m also still pleasantly mystified by our obsession with food – our need to talk about it, remember it, photograph it and analyse it, to eat our feelings and compare our lives to buffets and boxes of chocolates.

‘Good food is always a trouble,’ declared the influential British cookery writer Elizabeth David, ‘and its preparation should be regarded as a labour of love.’ This statement is classic David, which is to say that it, like her, brooks no argument (legend has it that David exhorted the beloved cookware brand Le Creuset to add a new shade of blue to its colour range by pointing at a pack of Gauloises, her favourite French cigarettes, and saying, ‘that’s the blue I want’). And you could apply David’s words as much to writing about food as to cooking it – not always the trouble, perhaps, but the labour of love, the urge to dissect our hungers and our hankerings or, dare I say, to spend several years studying cookbooks.

But is there anything new left to say?

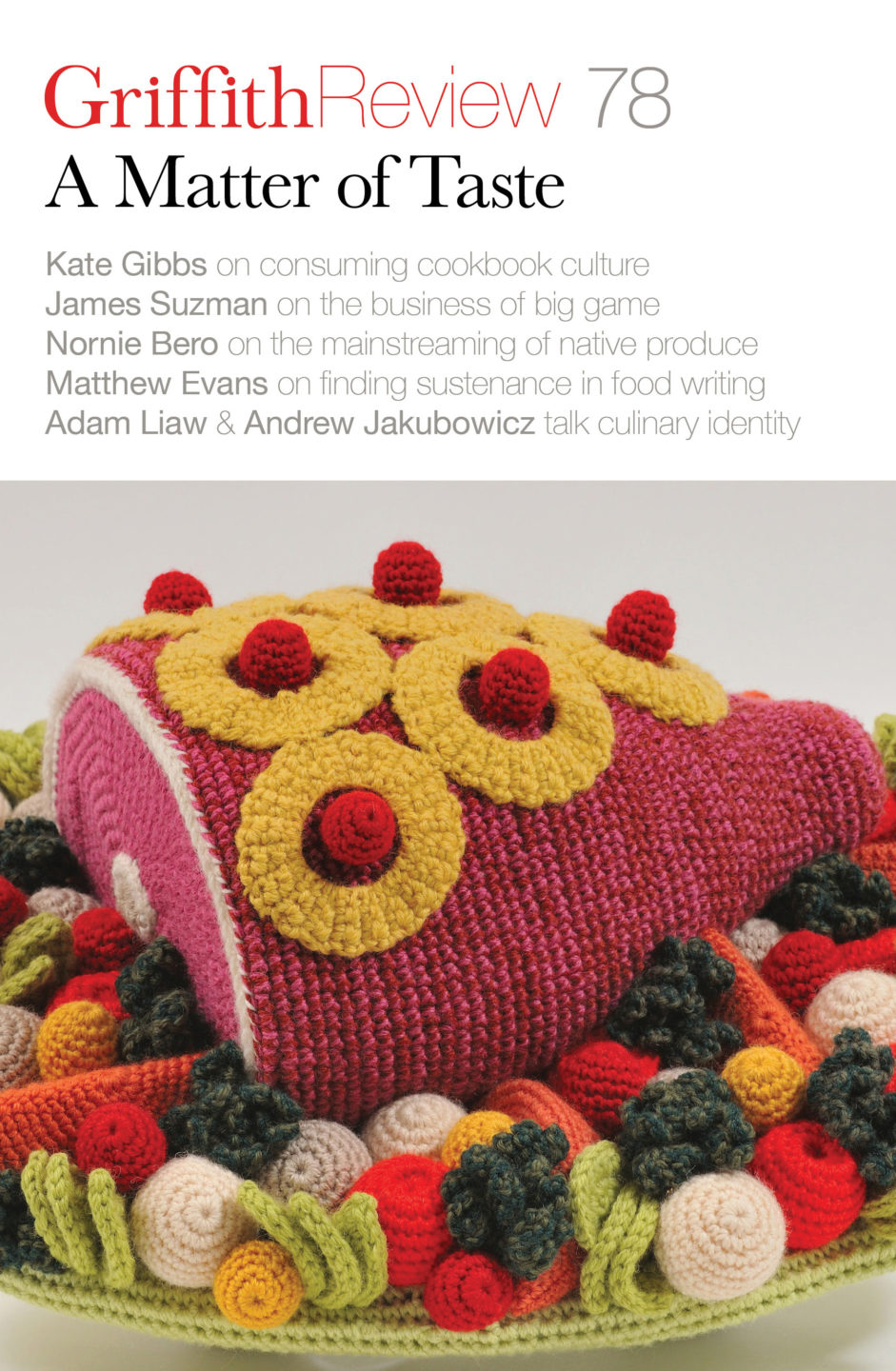

The short answer is yes; the long answer is this book. A Matter of Taste travels from suburban kitchens to grassy paddocks, from Europe’s medieval alehouses to Africa’s Kalahari Desert, from the shores of the Torres Strait to the restaurants of inner-city Melbourne; it goes from confectionery controversy to lockdown baking, from the milk wars to the hunt for the perfect blueberry, from Whitlam’s multicultural vision to Instagram’s wellness warriors, from cannibalism to cookbook consumption. In its mix of essay, memoir, reportage, fiction, poetry and visual art, this edition serves up a smorgasbord of food’s fascinating flavours: social currency, class identifier, cultural signifier, income generator, conversation starter, consumer product, art object, photography subject, scandal inciter, mythological symbol and more. And these pieces represent but a slice of what there is to be said on the subject of food, for which our appetites – literal and figurative – will never wane.

THIS EDITION OF Griffith Review also marks a new era for the journal. I took over as editor in June 2022 and, with the hard work, expertise and good humour of my excellent colleagues, I’m looking forward to putting so much more of the best new writing and ideas from Australia and beyond into your hands. I’m especially delighted to be debuting my stint in the editor’s chair with an edition themed around food – it’s been a real treat to curate this collection and to work with all the talented writers featured in its pages.

I’d like to acknowledge former editor Ashley Hay for her editorial contribution to two of the essays in this book: Laura Elvery’s ‘Confected outrage’ and Nicole Hasham’s ‘Big Blueberry’. Thanks to the Graeme Wood Foundation for making possible the Griffith Review Varuna Writers’ Residencies that supported the development of these two works. Thanks also to the Whitlam Institute for their support of our intergenerational conversation series marking the fiftieth anniversary of the 1972 election – the final instalment is published here. And thank you to the Copyright Agency Cultural Fund for their support of Griffith Review’s2022 Emerging Voices competition – two of the five winning stories, Stephanie Barham’s ‘Old stars’ and Melanie Myers’ ‘Fallen apples’, are featured in A Matter of Taste. We’re looking forward to publishing the other three winners in the first half of 2023.

My hope for this edition, once it lands on your bookshelf or your bedside table, is that it ends up like all my favourite recipe collections: dog-eared, food-stained, spine-cracked, bearing the battle wounds of a book that must be returned to again and again and again. (And if not – it’ll make a great coaster.)

16 September 2022

Image credit: Mimzy from Pixabay

Share article

More from author

The comfort of objects

Objects can be powerful mnemonics that connect us to stories and the places they were acquired. I have always had an interest in the things we collect and the way we arrange them in our homes. Being an artist, I like to create a place for these objects – an installation of sorts – within the domestic space, for my pleasure and for those who visit. The objects that appear in Open House are still lifes that the sitter interacts with and gives reason to their being.

More from this edition

Dried milk

Memoir THE RUIN OF the new mother is the raspberry. I give Yasmin, her eight-month-old, the bursting prize of the red berry. I know what I am doing....

Lunch at the dream house

FictionThere were columns. It was white. Palatial. ‘Just smile and nod,’ Paul said, as he drove towards the fountain where a replica of Michelangelo’s Bacchus stood in all his glory.

Easter cakes

MemoirI find I cannot cry on the day of the funeral or for many nights after the news of Ellen’s death and it is as if I am stunned by this loss, as if I am too close to this absence for it to mean anything yet, until two weeks later when I take the handle of the mould in my hands and lay the flat back of it against my cheek, and I cry and I cry.