Featured in

- Published 20230502

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-83-2

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

About the author

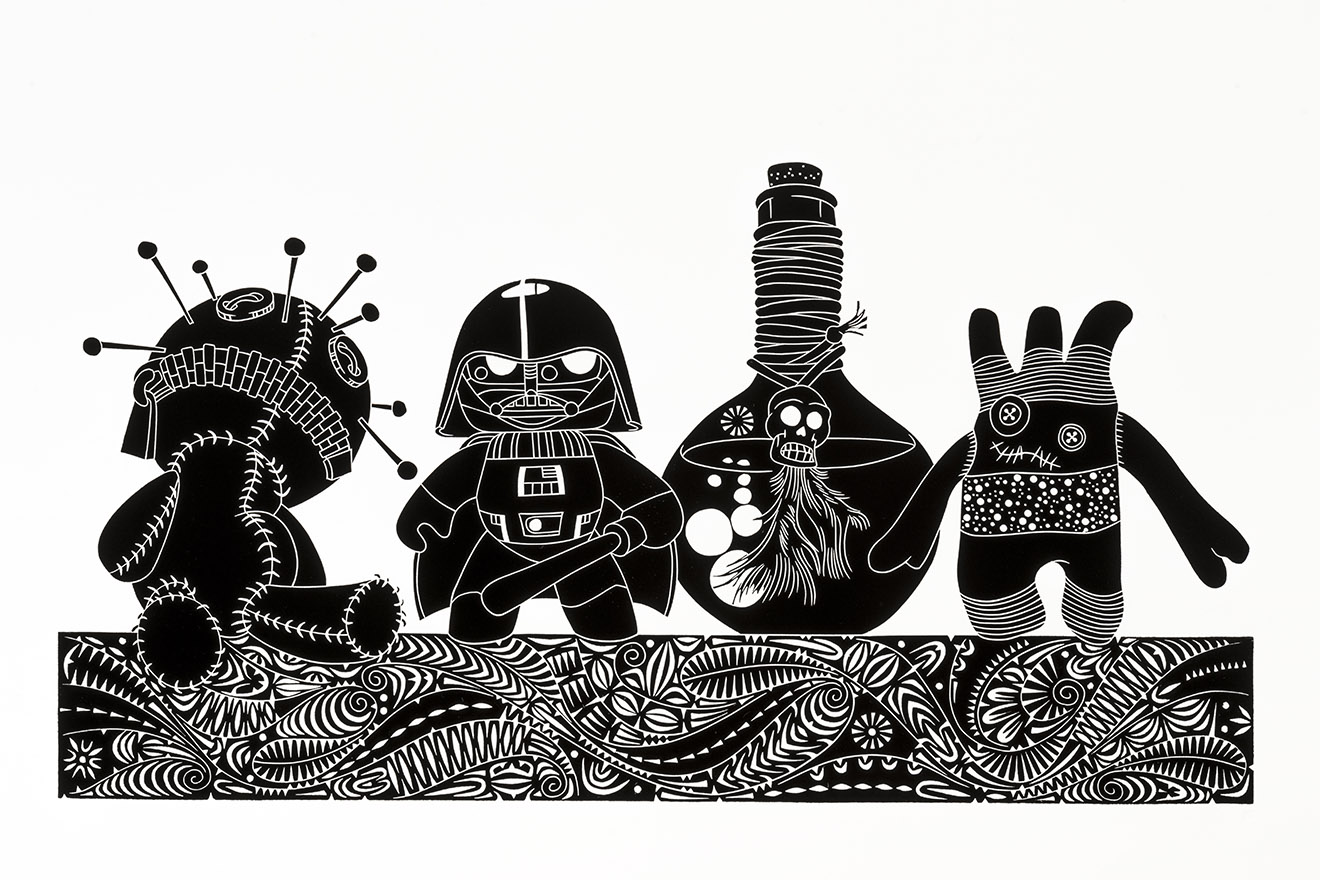

Brian Robinson

Brian Robinson was raised on Waiben (Thursday Island) and is now based in Cairns. He has become known for his intricate prints, bold sculpture...

More from this edition

Let there be light

IntroductionWhether they’re personal, cultural or religious, these are the stories that offer us ways of orienting ourselves amid the sheer chaos and confusion of being alive – particularly today, as humanity’s existential and environmental crises continue to mount.

On the right track

Non-fictionWhen the National Cultural Policy was released, the Albanese government stated their commitment to developing legislation to protect Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property. At last there will be a legal framework which can not only protect Indigenous peoples’ rights, but also set the pathway for better sharing of culture and greater respect for Indigenous cultures as the oldest living cultures in the world.

The transhuman era

Non-fictionThe story of the transhuman era has much in common with the creation myths of old – and with religious tales of transcendence. It heralds the emergence of a powerful – omniscient, omnipresent – force (AI) possessing intelligence that far exceeds our own. And lends itself to stories that play off destruction against what you could term ‘salvation’, in the form of digital immortality.