On ‘Ninu’ and ‘Two sisters’

A special series in celebration of the International Year of Indigenous Languages

Featured in

- Published 20191105

- ISBN: 9781925773804

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this essay contains the names of people who are deceased.

Nura Nungulka Ward, Ninu – grandmothers’ law, the autobiography of Nura Nungalka Ward (Magabala, 2018)

Eirlys Richards, Jukuna Mona Chugun, Ngarta Jinny Bent and Pat Lowe, Two sisters: Ngarta & Jukuna (originally published by Freemantle Press, reissued in 2016 by Magabala)

THESE TWO AUTOBIOGRAPHIES are written in English and interspersed with language – that of the Pitjantjatjara from the Central Australian desert in South Australia and the Walmajarri from the Great Sandy Desert in Western Australia. The translations are evocative and compelling, and both languages have extensive resources available online and in print. These books are portraits of deeply traditional women emerging into a changing world. Together they are two of the most significant female stories that our country is honoured to have in print today. They are epics of survival, by turns tragic, instructional, emotive, educational and soaring. They demand a readership.

In Ninu – grandmothers’ law, Nura Nungalka Ward, a Yankunytjatjara woman who passed away in 2013, tells the story of her life. It ripples backwards and forwards in time: while she ruminates and recollects the past and present, we learn about her elders, her hopes and her heavy heart for the future. Above all, Nura wanted the younger generations to read this story. Throughout the book, she passes down healthcare advice, midwifery skills, mothering and grandmothering knowledge to help boys become proud men and girls become strong women. She refers again and again to the power of hunting and to living in harmony with the land. This book contains all of Nura’s heart, all of her knowledge; pinned to this are her deepest hopes for her people.

Ninu opens with a foreword by Nura’s niece Melissa Thompson, who states that Nura ‘grew me up’. The reader is thrust into the family immediately, and from there, the book unfurls like only a work of this intensity could – in the most deeply personal way.

In the chapters that follow, we discover Nura’s culture, her dance, her name and the land her mother came from – a place too sacred to utter. We find out about her family, her parents and grandparents, her birth and childhood, and her long travels throughout the country. She chronicles falling asleep to the sound of storytelling, the Alpiri male hunters of the family coming to announce the day to the group, women’s ceremonies and dances, and learning about different insects and animals:

And so we learnt. We learnt how to hunt and dig and get our own meat. We learnt how to survive and how to feed ourselves. We learnt how to dig out rabbit burrows and how to get meat – real meat – real, solid, life-sustaining meat. Proper meat. We were taught how to dig properly in order to sustain our energy so we could keep going until we got the meat. We could hunt and feed ourselves when we were children. We loved it. We’d be so proud when we caught our own meat! We were happy, obedient, compliant and participatory.

Nura also writes about her marriage to Bully Ward Tjarutja, and about her working life as a respected health worker, a community leader, an inspirational First Nations woman, a globetrotter, a representative:

I have a big history, with big stories, a big true history. Tjukurpa mulapa, true history; knowledge, mulapa, true knowledge. I have learnt so many things in so many ways in my lifetime, in ways that are equivalent from pre-school to school to university. I’ve been taught the Law and the way of life from all my relatives: from my mother and father, my grandmother and grandfather, my older sister and older brother and all in between.

Nura’s final chapter is her grandmother’s story, a powerful reckoning with a country that has changed beyond recognition since her grandmother’s birth. It is Nura’s love letter to all that has gone before her, and all that is still to come. Throughout the book, Nura laments that the younger generation aren’t interested in the old ways. It is heartbreaking to read these passages, and the reader can only hope that this work is used to challenge what Nura saw as a great tragedy of her people.

That Nura’s name is not a household one is bewildering. To read this book is to be fed with the knowledge that its source is more powerful than words, to be truly nourished. This book is a great legacy, an enthralling read and nothing short of a very sacred thing.

TWO SISTERS: NGARTA & Jukuna opens with an illuminating introduction by Pat Lowe, who met Ngarta in 1986 and encouraged and assisted her with telling this story:

The First World War came and went, and left no impression in the sandhills. Two decades later, the Second World War had faint reverberations. News reached the desert that the white people were fighting an enemy from overseas, and formations of aircraft appeared in the sky. These were probably on training exercises from air bases such as the one at Noonkanbah in the Kimberley. No one in the desert had heard of Adolf Hitler.

None of the desert people knew about the Royal Visit of the young Queen Elizabeth in 1953, or would have had any idea of what it was all about. The Melbourne Olympics three years later caused not a ripple in the lives of Ngarta, Jukuna and their family. Robert Menzies, of whom they knew nothing, was Prime Minister when Jukuna and later Ngarta emerged from the Great Sandy Desert. It would be much later before they first heard the word ‘Australia’ and learned that they were not only Walmajarri, but also Australians.

The chapters that follow alternate between English and Walmajarri. In Magabala’s reissued edition, behind the beautiful black cover are inserts of photographs and the sisters’ artworks (they were both internationally renowned artists). The images are secondary to the text; the sheer power of the sisters’ lives remains in their words and their story.

Ngarta and Jukuna were from the Great Sandy Desert, and lived through a period of change – the Walmajarri people, who had lived for so long with no knowledge of the outside world, had started to move onto cattle stations. In 1961, Jukuna and her new husband left Tapu, her family’s main jila (camp), and young Ngarta stayed behind with a group of women and children, including her mother. But when violence struck, Ngarta finally, heartachingly, left the camp. Pursued by two murderers, she entered the desert alone to find safety: ‘So I went away on my own, in the afternoon. I went west. I took only a kana (digging stick) for hunting and a firestick. I walked on the grass all the way, till I got to Jarirri.’ Ngarta evaded capture by walking atop spinifex plants so that she left no footprints. For a year, she lived alone in the desert. Her harrowing story of survival cannot be adequately summed up – it must be read first-hand. Jukuna’s story is similarly striking: she experienced her own journey of migration across the desert, her own tale of womanhood, mothering and survival.

Together, the sisters’ stories make a perfect whole: they are two halves of the Great Sandy Desert. Ngarta and Jukuna’s paintings depict the waterholes and stark landscape of these stories in rich, joyful colour. Ngarta helped create an enormous painting of ‘all the important waterholes’ of their land ‘to show the government when we asked them for Native Title to our country’. That native title claim was successful – in 2009, the Ngurrara group was granted over 78,000 square kilometres in the Great Sandy Desert to protect and preserve.

The afterword by one of the book’s other contributors, Eirlys Richards, illustrates the important language work that would become central to Jukuna’s life:

Jukuna and her family came to live in Fitzroy Crossing. Her husband, Pijaji, came to our men’s Walmajarri reading class and learned to read and write the language. When the women’s class started, Jukuna was there with her youngest child, who was barely a toddler. By 1980 she was a fluent reader, one of a small number of people who could read and write the language. Walmajarri literature at that time consisted of a collection of booklets of personal experiences, and translations from the Bible. Jukuna mostly liked reading the Bible, which she helped translate. Her skill in writing did not develop as quickly as her reading did, probably because there was little reason for her to write. By the late 1990s I was no longer living at Fitzroy Crossing, but my work often took me through the town. On one of those occasions, when I was visiting Jukuna at her home in Bayulu, just outside the town, she reached into her bag saying she had written something and wanted to show it to me. To my surprise, she produced a writing pad with three or four pages filled with her Walmajarri writing. ‘I have written a story about myself,’ she said. ‘Will you read it?’

These two sisters’ lives are richly, honestly and forever survived on the page in Walmajarri. For all Australians, it is an honour to hold this book in our hands.

Share article

More from author

The books we carry on our backs: 1796–1996

During the period of colonisation, Aboriginal customs and languages were prohibited from being used and spoken, which meant that many languages and their stories disappeared from circulation. A great linguistic dispossession occurred, hand in hand with a great dispossession of homelands and family structures.

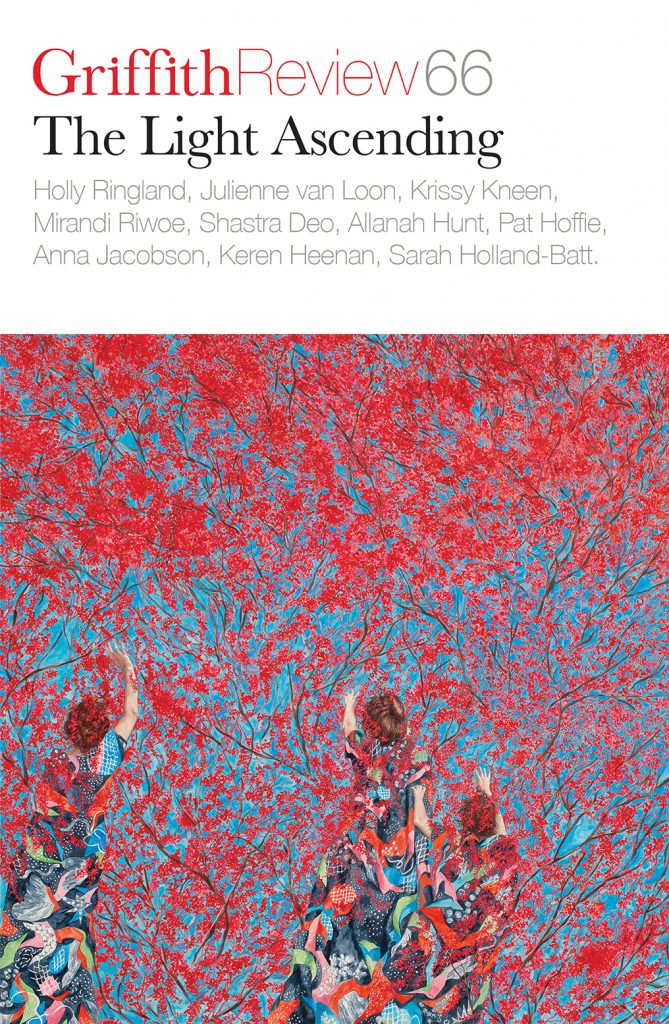

More from this edition

In the small hours

IntroductionClick here to listen to Editor Ashley Hay read ‘In the small hours: Stories from madrugada’. THIS MORNING, I was up at 5 am. The city sky was...

The market seller

FictionFor as long as she could, Emily hung back among the shelves of her shop. Being near books was one of the few things that truly comforted her. Her love of fairytales in particular, for the hope in darkness within them, had been the reason she’d started her market bookshop after Robert left her with barely anything following their divorce. Emily picked up a Victorian anthology of fairytales and poems, ran her fingertips along its edges, thinking of all the ways second chances might arrive in a life. Of how much she had to offer someone, how much love she had to give, if only she could find the courage.

2019: Future voices

GR Online Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this essay contains the names of people who are deceased. THIS YEAR WAS always going to be significant – 2019...