Featured in

- Published 20191105

- ISBN: 9781925773804

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Click here to listen to Editor Ashley Hay read ‘In the small hours: Stories from madrugada’.

THIS MORNING, I was up at 5 am. The city sky was a layer of pewter rather than darkness, too sparsely starred, and every living thing was the shadow of itself in different depths of black. What lights I could see were streetlights, pools of orange on the main road nearby, and saucers of bright whiteness in the park that runs between that road and the smaller street that goes by our place. It was cool, twelve degrees, a Brisbane winter, and two kinds of birds were already talking: here comes the morning.

My back door faces south-east, and one bright star was framed by the doorway – Sirius, the Dog Star, the brightest star in the night sky. Sirius is only 8.6 light-years away. To see its light is to see the recent past – the light of early 2011, before the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, before the start of the Libyan and Syrian civil wars, the Tunisian or Egyptian revolutions; before Occupy Wall Street or the death of Osama bin Laden. That’s when this light set out from its home.

Just to the north, a fingernail of orange moon hung low, a waning crescent, and the sky began to change behind its shape.

At 5.37, the first kookaburra called, and the colour of the morning came through a kind of purple that leaned towards silver and gold – it was a lightening, rather than a colouring of the space. The Spanish call this time the madrugada, the earliest morning, before sunrise; the twilight of the dawn. The bank of trees between me and the horizon stayed black and solid, a stable point of comparison for the varying sky. At 5.49 there came a second kookaburra cry, and with the instant of hearing its call came the moment of seeing the day’s shape. The colour was coming back into the world – in the sky first, a yellowing, a kind of orange, but these colours were only suggested against an opalescent white. One last fruit bat flew over; the stars began to bleach or leach away. And against all this movement in the sky, the trees and the grass stayed resolutely night-timed.

There were layers of bird call then, and the moon’s fine crescent of orange shifted back to silver, the rest of its circle pressed against the changing sky.

The world was coming back into itself: some of the trees tilted towards green while others held their darkness. The air was still: all pause, all observation, while a massive flaring change burned red beyond the closest line of trees. Over there, it wasn’t that the sun was rising, but the Earth kept falling forwards.

And in an instant, all the trees had found their colour, resolving themselves from solid black to so many individual green leaves – visible, in this moment, for the first time.

The first bird launched itself into the sky, a punctuating flutter that rose and looped and turned, trying out the size of the new day. There was a kind of blueness overhead, but it was a more peripheral, side-glanced thing, and the horizon’s edges – south around to north – still held their golds and pinks.

A magpie and a galah flew in and settled on the wiring: the air shifted, and the sunrise had arrived.

IT’S GALVANISING TO witness a new day’s beginning: it’s a small piece of time freighted with promise and potential – both in the real world, and in so many versions and varieties of our stories, our paintings, our films. It’s revelation and quantification. It’s a kind of resurrection and return. It’s an escape or a transcendence from the darkness. It opens out the space where whatever is going to happen on this next day, this new day, can take place.

If this dawning, this beginning, represents the start of a new story, then the words in this edition of Griffith Review – four novellas, two fellowship winners, new short fiction from one of Australia’s brightest writing stars and a complement of new poetry – each set out from their own distinct points of illumination. A woman takes a hill too fast on her bike and flies into a new world; three misfits walk towards the space of new performance, a new home; a grandmother is recovered from fable, fairytale and Egypt; a heartbroken sister sells sublime sweetness to her old town; a pleasure dome glistens and shimmers on the edge of colonial Brisbane, a magic black panther tucked into the centre of itself; a family confronts a moment of loss and violence; a young girl transcends the strange gaze visited on any muse. These are stories of exploration and revelation; tales of taking flight and breaking free; tales of discovery and recovery.

They’re a handful of narrative mornings; they’re starting points for change.

We’re grateful to the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund for its support for the novella project, now in its seventh year; to Arts Queensland for its support for the Griffith Review Queensland Writing Fellows featured here; and to the Australia Council as always for its ongoing support of our writers. Particular thanks also to the Novella Project’s external judges this year: Maxine Beneba Clarke, Holden Sheppard and Aviva Tuffield.

It’s at the beginning and end of each day that both the light’s change and the Earth’s movement are most obvious – in the same way that we designate the beginning and end of each year as pieces of time with different potentials or resonances. Yet the light is moving every second of the day, whether we notice, whether we understand its passage. Whether we understand that change is always underway.

As this year swings round towards its end and our next summer starts, perhaps we can seek out other ways of being, bear witness to explorations, escapes and ascents. Or at least pause and pay attention for a while.

THIS EVENING, I was out at 5 pm: the western sky was blazing and the trunks of the park’s trees were polished to rose gold. Another return. Another kookaburra’s call. And then the colour started fading down as the sunset came on, diminished again until the next morning’s dawn, the leaves and trees and grass all slipping back to black.

It will be 2027 before today’s sunlight reaches Sirius. But on Earth, at every second of the day, somewhere, there’s a sunrise, and a moment when the colour comes back to the world. Now, and now, and now, somewhere, the sun is rising.

Go well through the coming summer days.

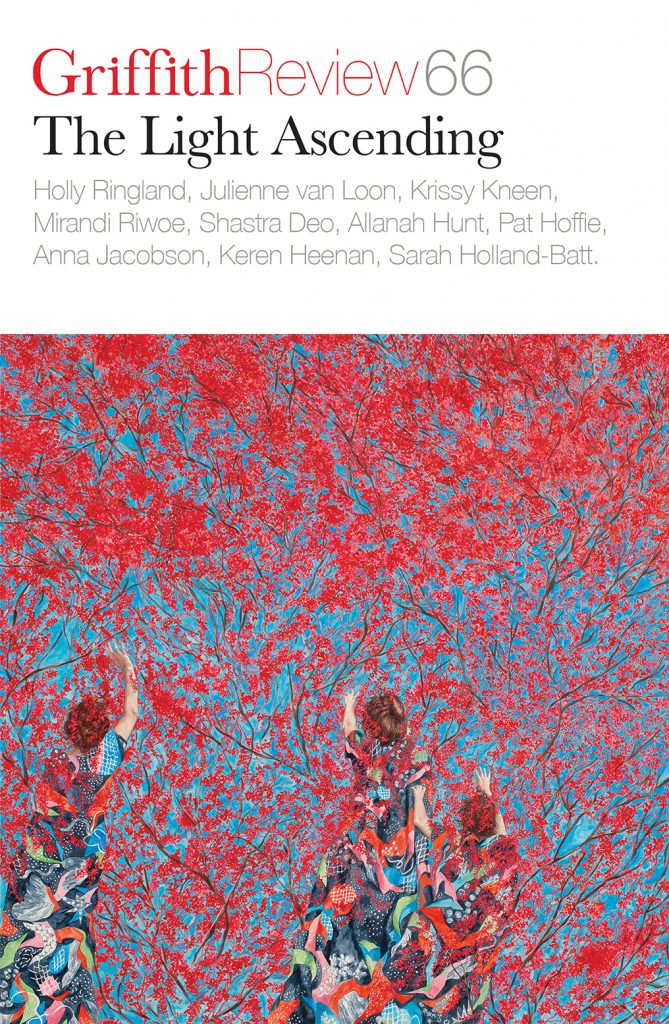

Cover image: Monica Rohan, Cold frizzle 2016 [detail]

Share article

More from author

Between different worlds

IntroductionAntarctica offers windows into many different worlds...

More from this edition

The morning fog (A Golden Shovel after Kate Bush)

Poetryis sweetest at the Tropic of Capricorn, the colour of lemon chiffon cake, and just as light. It might begin with a ringing of hands, it...

Orison

PoetryThree days later, we bought a Newton’s cradle. Put it on the table, and heartsick, tried to click click click our way out of it. But there are...

Routines

PoetryAbout once a day I think about the wetness of Ellen’s eyes as Obama placed the Presidential Medal of Freedom around her neck. The...