Featured in

- Published 20190806

- ISBN: 9781925773798

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

Possession

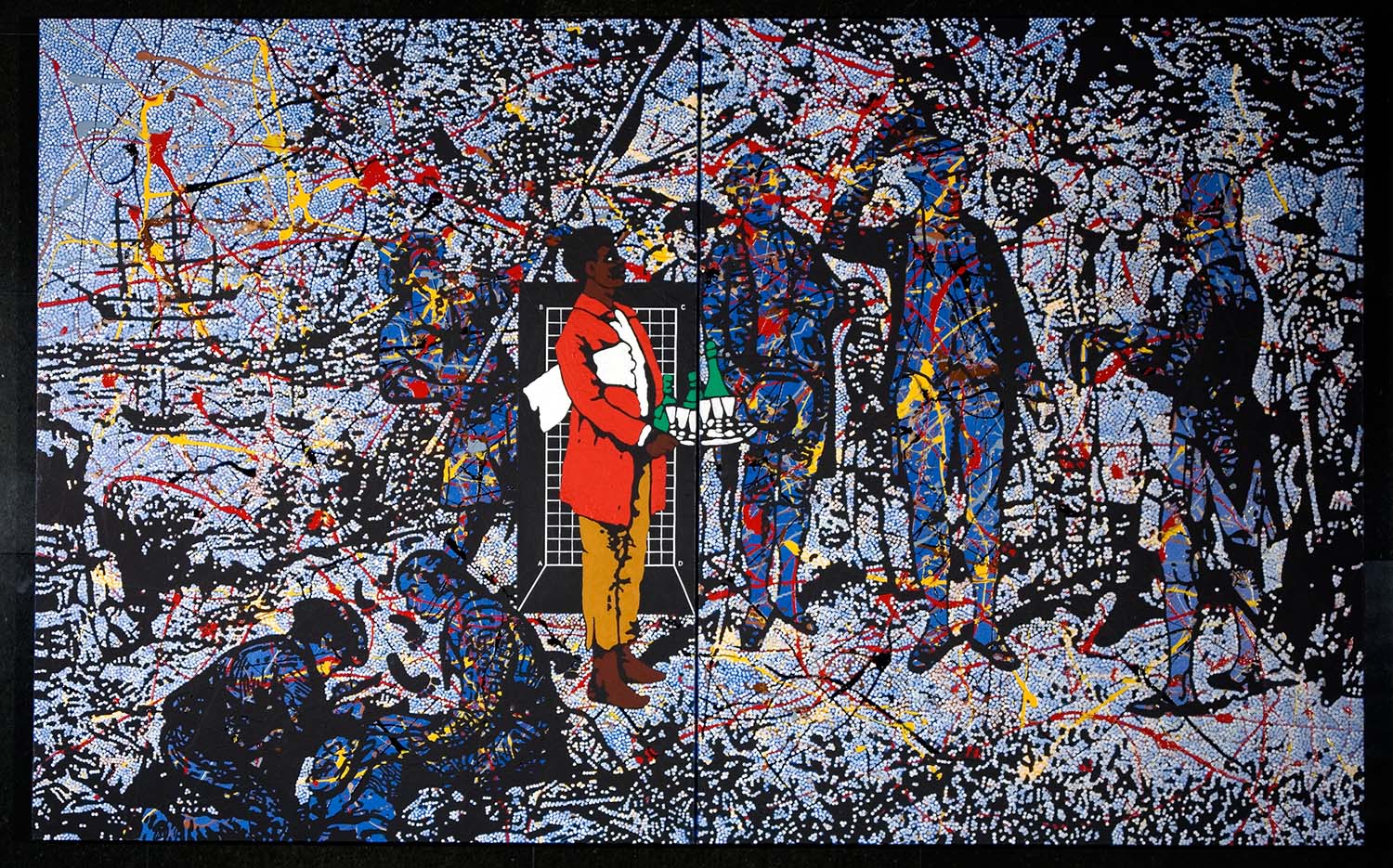

Bennett chose to excavate representations of colonial history. Old paintings, drawings, stamps, newspapers and textbooks – the kit and caboodle of scenes, images, stories and tropes that, in sum, form something like Australia’s visual common sense. It is just this assemblage that Gordon Bennett sought to unsettle in Possession Island.

More from this edition

Reassessing the reoffending question

GR OnlineWHEN INDIGENOUS SENTENCING courts began to develop in Australia in the early 2000s, governments promoted the view that the courts could reduce the Indigenous...

Adjudged

PoetryWilliam Spalyng, who, for selling putrid beef…was put upon the pillory, and the carcasses were burnt beneath. Arthur Griffiths, The Chronicles of Newgate Justin R Haymaker,...

White justice, black suffering

ReportageDad began this job in 1989 in the days of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. He was not the only black prison guard on staff – in fact, at one point, Rockhampton’s jail had the highest percentage of Indigenous employees in the state. And yet, there were even more Murris locked up. The first thing that shocked Dad was just how many were inside, and over the next two decades he would see many of his own relatives coming through the gates.