Featured in

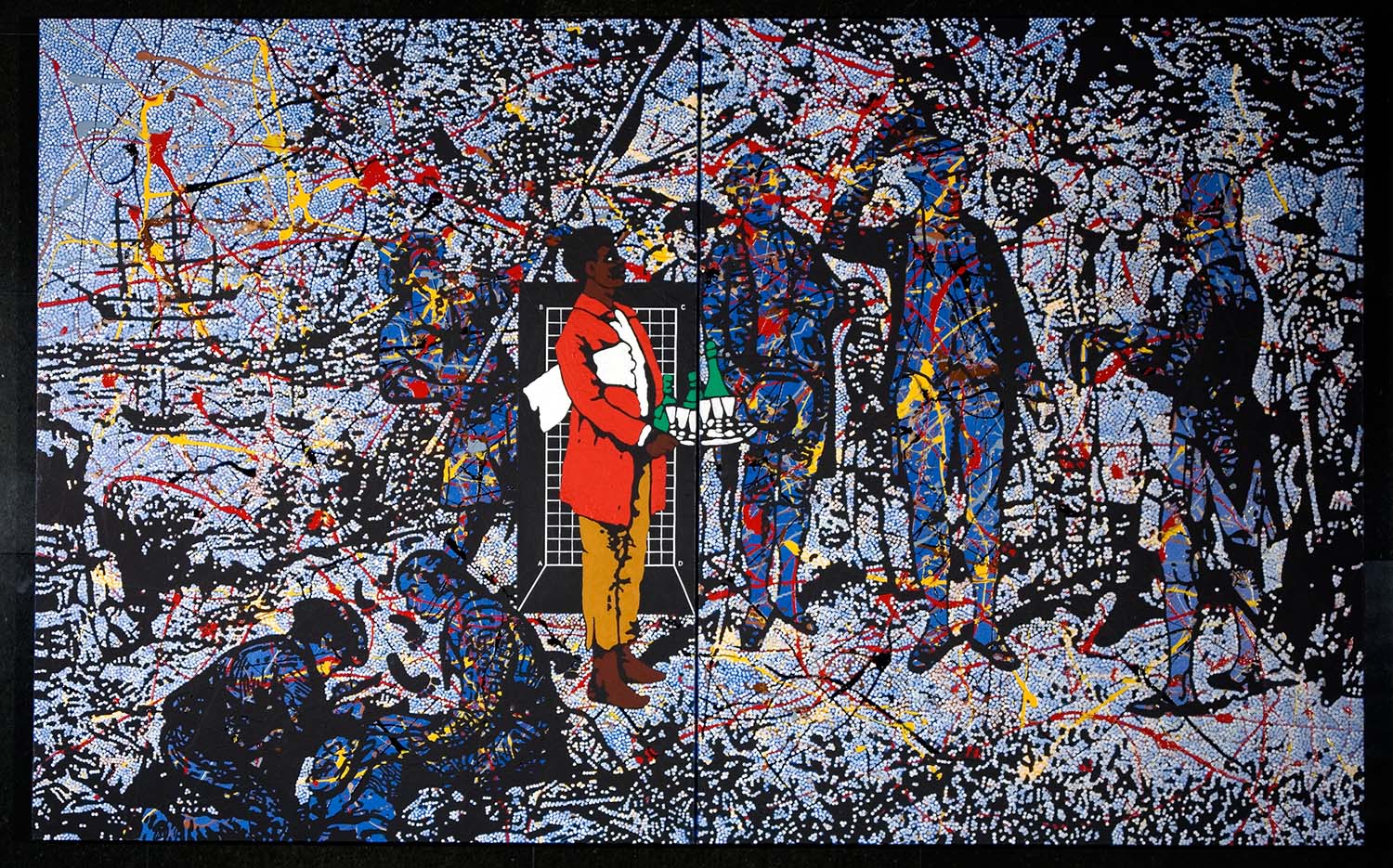

Figure 1. Gordon Bennett (1955-2014), Possession Island, 1991, oil and synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 162 × 260 cm; Collection: Museum of Sydney on the site of first Government House, Historic Houses Trust, purchased with funds provided by the Foundation of the Museums of History New South Wales Museum of Sydney appeal, 2007; image courtesy The Estate of Gordon Bennett and Museum of Sydney, © The Estate of Gordon Bennett

HOT ON THE heels of a major survey of the great Australian artist Gordon Bennett (1955–2014) mounted at the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) in Queensland came A Year in Art: Australia 1992 at the Tate Modern in London in 2021. As a result of Covid and closed borders, few Australians have, unfortunately, had a chance to see it. With the exhibition continuing into the coming northern autumn, we can but hope.

1992 was the year that Australia’s High Court, in the Mabo case, at last recognised the native title of Indigenous people, overturning centuries of legal practice concerning terra nullius along the way. 1992 was also the year that Bennett’s Possession Island 1991 (fig. 1) was first exhibited, at Bellas Gallery in Brisbane. It is fitting that this remarkable work’s sequel, Possession Island (Abstraction) 1991–92 (fig. 2), sits at the heart of the Tate show. Stretching over 1.8 metres square, its size matches its ambition – reimagining, and deconstructing, nothing less than the birth of the Australian nation. In fact, Bennett produced three versions of this painting. As I wrote this piece through late 2021, locked down in Canberra and far from London, my focus was on the slightly different version, Possession Island, which had just been exhibited at GOMA.

The date is 22 August 1770. And the place is Possession Island, an isolated speck off the coast of Far North Queensland. A Black man, smartly dressed in red and gold, carries a tray of drinks. Beside him, Captain Cook and his men salute the Union Jack. But next to the vivid Black figure they are a pallid and indistinct bunch, hardly more than sketches or outlines, covered over with splotches and dribbles of paint in soft shades of red, yellow, black, white and blue. What on Earth is going on?

When Captain Cook planted that flag ‘on Australian soil’ in 1770, the entire continent became part of the British Empire. In an instant, a legal system was transplanted to fill the vacuum left by an empty land – terra nullius. This story was, and in many cases still is, taught in classes on constitutional law across the country as if it were a simple legal fact. That’s certainly how I learnt it back in the 1980s: from that day on, British law covered the whole of Australia.

But in what sense can such a claim be true when almost a million Aboriginal people were then living under their own laws right across the continent? Almost none of them even saw a white man until many years, even a century, later. And how could Cook claim to have conquered a continent not fully mapped, and of which so-called Possession Island is not, geographically, a part?

What rendered this legal myth unproblematic for so long can best be termed the colonial imaginary. Australia’s national coming-of-age stories have always been dominated by shop-worn tropes – the stockman, the explorer, the settler, the squatter, the soldier, the native; wool, wheat and gold. Yet the unreal quality of these myths does not prevent them from generating real-world consequences. On the contrary, their mythic innocence shields them from scrutiny.

Many major contemporary Indigenous artists – including Fiona Foley, Julie Gough and Judy Watson – describe their work in terms of truth-telling. They seek to portray the real facts and events behind the so-called discovery, settlement and exploration of Australia: the real violence, the conflict, the massacres, the abductions, the discrimination and the exploitation behind the takeover of a whole continent. But Bennett approached the problem differently. He chose to excavate representations of colonial history. Old paintings, drawings, stamps, newspapers and textbooks – the kit and caboodle of scenes, images, stories and tropes that, in sum, form something like Australia’s visual common sense. It is just this assemblage that Gordon Bennett sought to unsettle in Possession Island.

BENNETT WAS NOT the first artist to depict the moment on tiny Possession Island when Cook asserted the rights of the British Empire over the entire continent of Australia. Bennett’s painting is actually a palimpsest, based on an earlier image originally painted by JA Gilfillan in 1857 with the title Captain Cook Taking Possession of the Australian Continent on Behalf of the British Crown, AD 1770, Under the Name of New South Wales. This painting, now lost, was etched by Samuel Calvert and published in the Illustrated Sydney News in 1865, almost a century after Cook’s visit. More drawings based in turn on Calvert’s reproduction made their way into libraries and school history textbooks for the next one hundred years. This is how myths work – copies of copies of copies, endlessly circulating, gradually acquiring the veneer of reality.

The scene, as Calvert and Gilfillan imagined it, reduces the local inhabitants to fauna, with the sole exception of that Black servant in European dress, who witnesses Cook’s actions. The hoisting of the colours in the name of the king, the show of force, the military parade with fife and drum, even the celebratory tipple, are all ritual actions. Captain Cook neither perceived the need nor asked for the consent of the natives in his colonial endeavours. But he did need witnesses to confirm that it had all been done in the proper form.

Yet this image, like many myths, jumbles up different events and times. The location looks less like Possession Island, way up in the tropics, than Port Jackson, 2,500 kilometres south. Port Jackson – Sydney – was of course the site of the penal colony not established until a full eighteen years after Cook’s voyage. Even the Union Jack in the picture is an anachronism. The United Kingdom did not come into existence until 1801. Possession and settlement, nation, empire and kingdom, thus fuse together in one fabulous fiction.

Perhaps the anomalous servant at the heart of the picture is also an anachronism – a time traveller, a ghost in reverse, some Indigenous man from the future transported back in time. Perhaps he is there to witness the whiteness of a European legal authority that would eventually domesticate him. In Western dress, bare foot, obedient, he is not just a witness to Empire: his transformation from a ‘savage’ to a docile British subject is the ultimate proof, the fait accompli, of British law.

BENNETT’S PAINTING REPRISES Calvert and Gilfillan’s iconic image. But in Bennett’s hands, the Black figure is given a dramatic prominence, set against a black and white geometric grid that feels like a portal in time. Cook and his servant lock eyes; it is the only real encounter that takes place. And in that look the witness suddenly accumulates not just a passive legal function but an active moral one. He highlights an alternative subject position from whose perspective the colonial story could be observed, remembered and judged – as indeed it still is. The original painting by Gilfillan invites us to see the performance of sovereign power from the British point of view, the witness playing a necessary but secondary role. Bennett reverses the gaze.

Meanwhile, the colours of Bennett’s Possession Island are the colours of flags and thus hint at possible futures. The imperial figures are faded and defaced by wild splashes of colour, like confetti from an exploded Union Jack. In contrast the Indigenous man is dressed in the bold colours of the Aboriginal flag. Only time will tell which of these prophecies of Australia will win out.

But Bennett’s squiggles and drizzles of colour are disorienting. Layered over the top of the original image, they are a purposeful nod to one of the key figures of artistic modernism, Jackson Pollock. Bennett’s juxtaposition of Pollock’s colourful and lively abstract art with an historical scene that took place 200 years earlier and half a world away seems at first glance perverse.

In fact Pollock unconsciously played a not insignificant role in recent Australian cultural history. Blue Poles, his huge 1952 masterpiece, was purchased by the fledgling Australian National Gallery in 1973. A storm of public controversy followed, with media commentators and conservative politicians letting off predictable steam about wasting public money on giant, childish scribbles. Nowadays the story is typically told as the moment in which Australia declared to the world its cultural independence – our postcolonial Possession Island, though perhaps it was simply the moment when we swapped our allegiance to the British Empire for the American one.

Bennett juxtaposes the histories of New York modernism and Australian colonialism very differently. He describes his use of ‘the over-painted modernist trace of a Pollock skein’ as ‘a metaphor for the scar as trace and memory of the colonial lash’. On the one hand, Pollock’s artworks were more visceral than aesthetic. In Blue Poles, among other works, lashings of paint capture the fury of physical exertion that the canvas absorbed exactly like the scar or memory of some violent impulse. His art does not represent an image but documents the aftermath of an action. On the other hand, Indigenous art itself is far from ornamental. The relationship between identity and Country is inscribed on the skin; the soft pores of canvas and the bodily fluidity of muddy ochre are physical ways of animating identity and belonging by practices that bring bodies and the land directly into contact. They are spiritual action paintings. There is a real if subterranean kinship between the Indigenous and the modern that goes far beyond their supposed abstraction.

Above all Bennett’s work tackles the chilling arrogance of the claims of the fine art tradition to transcend the corporeal, define the universal and to tell a story of aesthetic progress. Our art galleries often drum into us a bildungsroman, from rooms of ‘primitive art’ via the breakthroughs of the Renaissance to the giddy heights of modernity. But in Bennett’s eyes, this narrative of art echoes and conditions the narrative of colonialism. At stake in both art history and legal history is the irresistible march of civilisation from primitive to modern man. Possession Island reminds us of the violence in Australia’s colonial march of civilisation. Bennett juxtaposes the lash of the paint as it hits the canvas with the lash of the whip as it bites into flesh. Linking Pollock’s oozing red dribbles and blue poles with the welts and bruises left on human bodies, Possession Island exposes the relationship between intentions and effects, vision and blindness, purity and violence, stories of progress and hearts filled with hate.

BENNETT’S BODY OF work shines an equally subversive light on the coming-of-age story of Australian art, too. The impressionist movement, led by Frederick McCubbin, Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, paved the way for a distinctly Australian aesthetic. But they did so using romanticised images of the settler experience that, even in the 1880s, were nostalgic and backward looking. Their work celebrates the courage, struggle and triumph of the pioneers as they tamed an unforgiving land. There is a great deal that is false or hidden by such a narrative. McCubbin’s paintings, for example, never acknowledged the destruction of the physical environment entailed by a mere hundred years of violent conquest, nor the decimation of the Indigenous people who had lived in harmony with the land for more than 65,000 years.

Take Violet and Gold, painted by McCubbin in 1911. In this tranquil scene, set deep in the Australian bush, an early morning or late afternoon sun pierces the dense foliage, its light beatifying a few stray cows as they drink from a pool of clear water. The taming of the landscape, its conversion from wilderness to agricultural production, is subtly but powerfully celebrated. But look at the multicoloured and scratched surface of McCubbin’s canvas. His brushwork is carved, angular and splotchy. Up close – up very, very close – the picture is utterly unrecognisable. It dissolves into lines and scratches, a palette and texture that seems unmistakably Pollock-like in the violence of its action – forty years ahead of its time. Even the trees start to look like blue poles. The temporal narrative that divides Aboriginal, colonial and modern art collapses. So too the strict dichotomy between a colonised and decolonised mindset.

Like the central figure in Bennett’s painting, the anachronistic trace of Blue Poles in Violet and Gold leaves a haunting aftermath of colonial violence. Viewing McCubbin through Pollock and Pollock through Bennett offers an entirely new perspective on all three artists. We cannot unsee the ‘trace and memory of the colonial lash’ in the recesses of McCubbin’s bush and the rough scratches of his palette knife and brush. The brooding bush takes on a new inflection, as if the Aboriginal people that inhabited these places were still there – hidden witnesses subjecting us to their unseen gaze, or ghosts. McCubbin’s omissions are no longer simply an absence; they fill the image with a loss and a cry.

HOW WE UNDERSTAND the connections between, and politics of, these different art traditions matters. In 2016, the National Gallery in London devoted a major retrospective to the work of the Australian impressionists. The problematic myths behind their art were hardly mentioned. But, with Gordon Bennett’s work at its heart, Tate Modern’s A Year in Art: Australia 1992 does something altogether different. Through both legal and artistic frameworks, we can revisit our stale myths about the past and retell the narratives that shape a nation. The High Court’s decision in Mabo’s case, like a palimpsest, tried to write a new story over the top of terra nullius without erasing it entirely. So too Possession Island (Abstraction) paints a new story over the top of Captain Cook – without erasing it entirely.

Bennett’s response to the colonial myths of settlement employs a distinct temporal logic. Call it irony. He uses anachronistic and unexpected juxtapositions to unsettle how we think about an event or a history. Imperial powers are deadly scared of irony. It threatens to unpick their carefully curated narratives of power, progress and legitimacy. Irony queers our relation to the past, whether the past of colonial law or the past of colonial art. That has implications not just for how we think about the past, then, but how we think about ourselves, now.

The seat covers on Sydney buses strangely resemble Bennett’s Possession Island. A bright blue background covered in scrawls, splashes and lines of red and white. No doubt the echoes are unintentional. Nonetheless, thanks to the queer art of Gordon Bennett, they take us back to Port Jackson – Port Jackson Pollock that is: ground zero of the British Empire in Australia and of Australian modernism. They invite us to remember the trace of the colonial lash every time we take a seat.

Share article

More from author

Looking at the big picture

EssayTHEY WRITE MUSICALS about it in the US; swear by it in Canada; swear about it in Australia; and use as it as a...