Featured in

- Published 20230801

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-86-3

- Extent: 200pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

IN 2008, FINNISH performance artist Pilvi Takala embarked on an audacious project called The Trainee. For one month, she worked as a marketing intern at the global accounting firm Deloitte. Instead of carrying out the usual responsibilities expected of this role, Takala did…nothing.

Big deal, you might say – plenty of people idle away their time at the office. But it was the manner in which Takala did nothing – unashamedly, even ostentatiously – that made her co-workers, most of whom were unaware that she was engaged in a piece of performance art, uncomfortable and confused. Takala spent an entire day riding up and down in the lift; she sat at her desk with her hands in her lap, staring into space; she did the same in the tax department library. When asked what she was doing, she replied, ‘brain work’.

That’s a hard phrase to argue with. How do you disprove it? It also represents Takala’s broader artistic motivation, which is to make us question what behaviour we deem socially acceptable and why. In an office context, ‘doing nothing’ is an ambiguous term that can mean anything from reading clickbait headlines such as ‘Which cat breed are you?’ (I’ve definitely never taken this quiz) to online shopping or scrolling Instagram. Technically, these are all activities; they may not be the ones you’re being paid to perform, but performing them still allows you to convey the impression of productivity to your colleagues or superiors.

This appearance of busyness is essential to maintaining the social codes that govern the workplace. In spurning these codes, The Trainee reveals the surprisingly radical possibilities of a true commitment to ‘nothing’ – according to Takala’s website, ‘The non-doing person isn’t committed to any activity, so they have the potential for anything. It is non-doing that lacks a place in the general order of things, and thus it is a threat to order.’

A threat it may be to some – but for many of us, non-doing is a goal that feels frustratingly out of reach. As we grow busier and busier, our lives full of apps and devices that promise to save us labour and improve our selves while draining the hours and minutes from our days, we seem no closer to knowing how best to use our precious time.

ONE OF THE starting points for The Leisure Principle was John Maynard Keynes’ famous 1930 essay, ‘Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren’, in which he looks one hundred years ahead to an idyllic future in which, among other things, technological advances would have vastly improved our standard of living and we’d only have to work a cool three hours a day. While some of what Keynes predicted would come to pass (sadly not the part about the three-hour workday), the rapid growth of the global economy hasn’t given us that abundant leisure time he imagined. What went wrong?

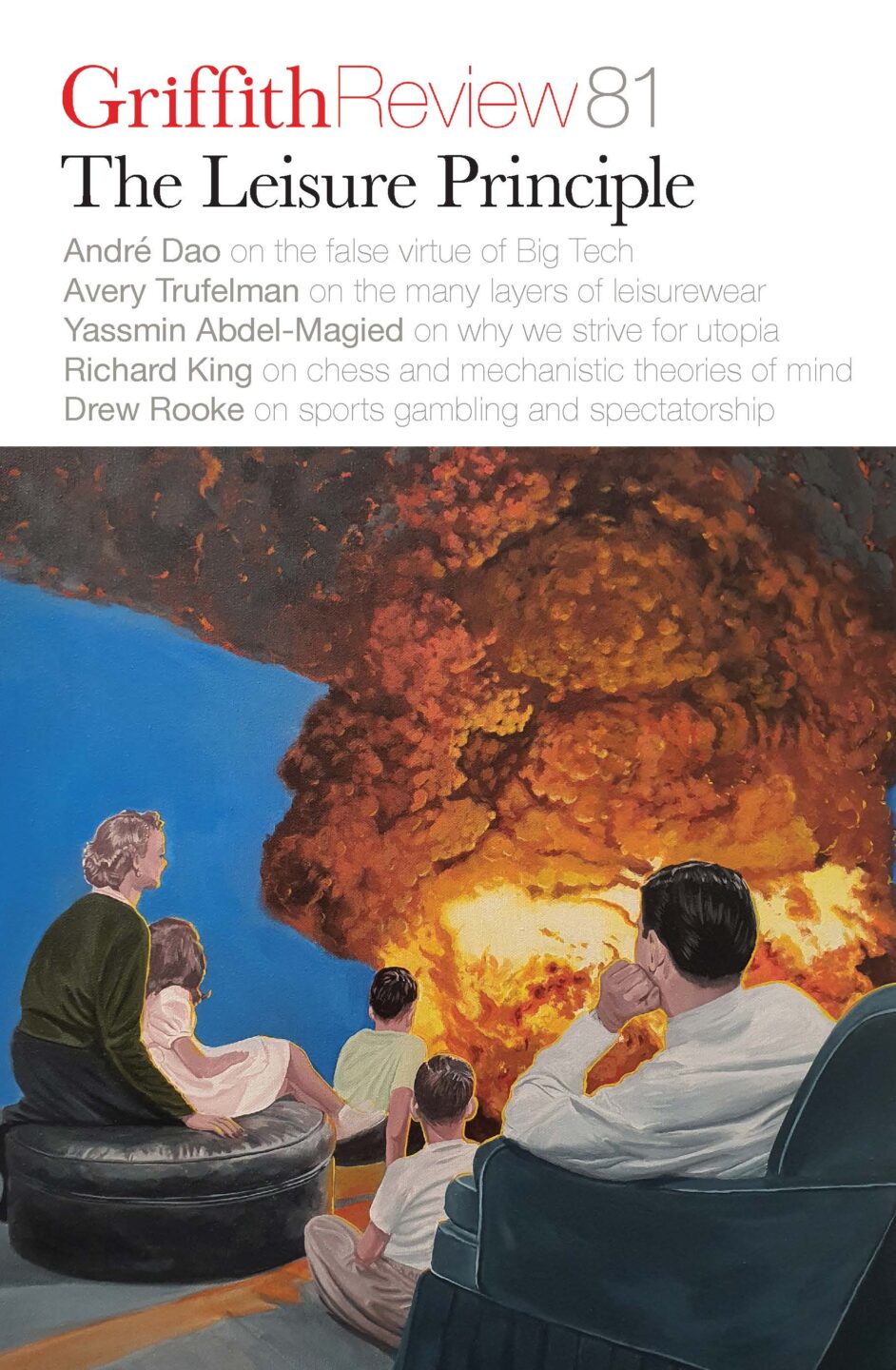

This edition of Griffith Review doesn’t profess to have all the answers, but it does promise a fascinating and thoughtful exploration of what leisure means to us today, how it’s evolved in the public imagination and what it might look like in the future. Maybe, as we look ahead to the next century, we can begin to realise the radical potential of non-doing and the ways in which it can upend an order that so often exhausts instead of fulfils us.

It’s apt that the editorial labour for this edition was shared among the Griffith Review team – Managing Editor John Tague, who also devised the theme, commissioned four stories (Russell Celyn Jones’ memoir ‘Revolutionary wave’, Jerath Head’s essay ‘The geography of respect’, Brendan Colley’s short story ‘Lying on grass’ and Drew Rooke’s essay ‘Upping the ante’); former Assistant Editor James Jiang commissioned Suneel Jethani’s essay ‘In the fullness of time’. I’d like to thank John and James for their editorial skill, insight and ideas – I never once caught them slacking off on the job.

If you choose to read The Leisure Principle during a quiet moment at your place of employment, perhaps you can call it research; perhaps you can simply say that it’s brain work.

22 May 2023

Image credit: Getty Images

Share article

More from author

Subject, object

The vivid hues and spiky leaves of Jason Moad’s Temple of Venus – the arresting artwork featured on the cover of Griffith Review 89: Here Be Monsters – raises a tantalisingly sinister proposition. The subject of the painting is clear – a Venus flytrap, realistically rendered – but there’s a somewhat otherworldly quality to this plant, a sense that it might be biding its time, waiting to strike while we, the viewers, are distracted by its beauty. For Melbourne-based realist painter Jason Moad, this slippage between subject and object, reality and imagination, is part of the point.

More from this edition

Salted

FictionWe are absorbed in our work until we are not. Mostly we take breaks together, sitting outside in the sunshine waiting for our thoughts to settle, waiting for our lives to begin. Gus and I have both applied for the same scholarship. We’ll find out at the end of the month. Eve is organising a group show and wanted my latest painting as the centrepiece, but I won’t finish it in time, so I drop out. ‘I’ve got something ready,’ says Gus. Easy enough to find someone to fill my place.

In the fullness of time

Non-fictionOur devices and data are more than extensions of our physical bodies. The so-called ‘human-centric’ approach to designing wearable and carriable devices means that they disrupt traditional divisions between work and leisure, production and consumption. It’s difficult not to feel the incursion of work-logics into leisure times and spaces as normal. Stretched for time, couples, families and friendship groups are starting to organise themselves using tools like Slack, Jira, Trello and Asana – that is, in the same way as workplaces.

Sonnet for the weekend

Poetry Glory to God for long weekends,for lattes served by obsequious baristas,sunnied eggs and bacon with the crispy ends,for an empty park in front of...