Featured in

- Published 20230801

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-86-3

- Extent: 196pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

HERE’S A SCENE from a film or television show that you’ve almost certainly watched: little kids joyfully bomb a resort pool, the arc of their descent one long plea for their parents’ attention. They’re ignored because Dad or Mum, or both, are on the phone (or, latterly, Zoom), talking about spreadsheets in a business voice until an accidental, but definitely moralising, splash lands on their face or, ruinously, the laptop they’re anxiously scanning. Anger flashes, the kids are crestfallen, the other parent looks on despairingly; the holiday mood is soured. A variation: a group of reverent birdwatchers pad through the undergrowth, peering up into the forest canopy until the silence is shattered by a man shouting into, and then at, his phone. He storms off swearing, hand upthrust in a fruitless search for signal, while just behind him a fabled bird settles on a branch, unseen. In both cases, and in the multitude of variations on this theme (not all of which implicate the pernicious effects of technology), we witness the judgement – the shaming – of those who squander the gift of family, friendship or nature when it is cocooned from the invasive demands of the workplace.

These corrective vignettes argue that leisure, properly appreciated, is a space of exemption from the impingements of the world. Of course, we know that isn’t the case for all sorts of reasons, not least of which that leisure is inevitably the product of someone else’s toil. That realisation, too, occasions further judgements on leisure’s uncritical consumers in all their environmentally ruinous and culturally insensitive enactments (see season one of White Lotus which, helpfully, anthologises versions of all the above examples). What I want to suggest here is that although shame appears to be the consequence of betraying leisure in the name of work, its regulatory function is – and always has been – intrinsic to the idea of leisure and its reformist potential.

IF YOU WERE a European peasant living in the Middle Ages, you would have heard a lot about the Land of Cockaigne. Its exact location varied, but it was always someplace remote and temperate of climate. In Cockaigne, where work was forbidden, rivers of wine bubbled past golden buildings formed from sweet pastry, while the beasts in the verdant fields proved ready roasted and delicious. Everyone wore magnificent clothes, sex was freely available and no one aged or fell ill. In his account of Cockaigne, the Dutch literary historian Herman Pleij describes the way that these fantasy worlds of perfect leisure proved powerfully consoling in the face of the frankly miserable circumstances of everyday life. Cockaigne was not in itself an answer to persistent questions about the scale of human suffering to be endured, but perhaps mentally occupying these utopias made it all a little more bearable, either as a kind of hyperbolic raillery among friends or a private reverie. By contrast, the Church’s explanation for misery rested more narrowly on the lasting consequences of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from a place not without its Cockaigne-like resemblances.

Depressingly, by the time the Cockaigne stories were recorded at the end of the Middle Ages, their meaning had flipped. They were no longer provocations to fantasise, for example, about worlds so innocent of food scarcity that literally everything the eye could see was edible. Instead, they summoned an upside-down world that detailed the opposite of what was desirable, and how one was not supposed to behave. That is, the stories were now understood in the shaming light of Christian teaching concerning unregulated desire generally, with gluttony in particular as the very worst of sins. Gluttons, it was said, defied the First Commandment by worshipping their bellies above God. So, even before the advent of modern leisure, when for most it only existed as a kind of thought experiment, it nonetheless furnished a space for moral instruction, a kind of shame trap to make ‘better’ people. This meliorist aspect of leisure persists in many forms but I’m going to focus on just one: the museum.

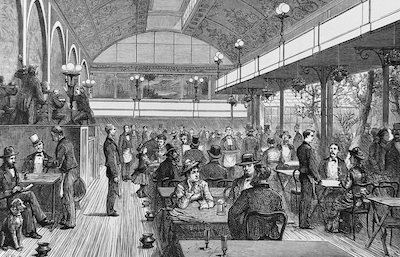

Modern leisure emerged in the West in the early 1700s when French and English cities developed new forms of society built around urban amenities – parks, cafés, fairs and shopping districts – servicing an expanding class of people with discretionary time and income. Public museums as storehouses of national culture appeared a little later in the nineteenth century where they contributed to the development of so-called ‘rational recreation’, a species of serious leisure intended to ‘civilise the masses’. The principles of rational recreation took shape in Victorian middle-class reform movements wholly preoccupied with the deleterious effects of working-class leisure. Museums and their allied institutions promised wholesome, improving and, above all, respectable distractions from the gravitational pull of the music hall, pub and gambling den. In time the reach of rational recreation would extend into the lower-middle classes themselves, which is how we arrive at the 1852 opening of London’s Museum of Ornamental Art in Marlborough House.

This museum’s signal contribution to the yoking of shame to leisure occurred in the so-called Gallery of False Principles in Decoration or, as it was known in the popular press, ‘The Chamber of Horrors’. The chamber was a narrow passage connecting two conventional display galleries within the museum. It contained what The Spectator described as eighty-seven ‘objects of daily use’, each of which, according to the exhibition catalogue, was remarkable ‘for their departure from every law and principle, and sometimes from even the plainest common sense, in their decoration’. The displayed objects included an electroplated gas fitting tipped with blue convolvulus shades, a pink-hued snake-shaped bottle, a ceramic flowerpot in the form of bundled reeds tied up with a yellow ribbon, scissors that closed to form the body of a stork and a large jug patterned to resemble a section of tree trunk. Admittedly, from a twenty-first-century perspective, it’s difficult to distinguish these florid, congested and dust-attracting items from what we might conjure up as the essence of Victoriana. As it turned out, this also proved an issue for visitors in 1852, not all of whom grasped the intended differences between the Gallery of False Principles and the regular exhibits elsewhere in the museum, seeing continuities where they were supposed to have understood contrasts. The Observer quoted a visitor who wrote, ‘It was amusing to hear the people admire the “false principles” when they first entered the room; from an impression that the articles were hung there in commendation.’ Understanding that, on exiting the chamber, you were moving out of a vulgar cavalcade and on to the good stuff, was an important, if intermittently successful, feature of the museum.

The exhibited ‘objects of daily use’ referred to the general category of affordable design but must also have comprised the kind of things that visitors to the museum were more than likely to possess – not just equivalent items, but the self-same goods, pinned nakedly to the wall for everyone to gawp at. Among the various responses to the chamber recorded in the press were just such mortifying scenes of recognition. You can appreciate the vertiginous trap set here: conventionally, and with the notable exception of some Indigenous items, which could be viewed as ‘curiosities’, Victorian institutional display practices were understood in terms of putting the ‘best thing’ on the plinth, except, as here in the chamber, where they suddenly ceased to do so in the curatorial equivalent of a ‘bait and switch’. Did pride-filled museum visitors dissolve into raw panic once they worked out the chamber’s darker purpose? Isn’t that our lamp? The Melroses’ carpet? The vicar’s tea tray? Imagine seeing your things suddenly revealed in a pitiless, public and institutionally authoritative light.

WHILE WE CANNOT know exactly how visitors felt in this moment when the chamber objects suddenly flipped from self-evidently museum-worthy to shamefully bad, we do have access to a fully realised fictional encounter in the form of Henry Morley’s satirical story ‘A House Full of Horrors’.

Morley’s story appeared in the 4 December 1852 issue of Charles Dickens’ journal Household Words, a publication addressed to middle-class aspiration and reformist concerns with the ‘lower orders’. ‘A House Full of Horrors’ charts the experience of a Mr Crumpet – London counting-house clerk, and tenant of Clump Lodge, Brixton – who, in the words of the narrator, has ‘recently sunk to the depths of misery’ because of what he has seen in the chamber. He described a gloomy space ‘hung round with frightful objects, in curtains, carpets, clothes, lamps and what not’, but there is something much, much worse:

I could have cried sir. I was ashamed of the pattern of my own trousers for I saw a piece of them hanging up there as a horror… I saw it all: when I went home, I found that I had been living among horrors up to that hour.

Before his visit, Crumpet delighted in all the cosy domesticity condensable in his buttery name, but now, shamed into a new understanding of aesthetic principles, his home and everything in it prove insupportable. That’s a desirable outcome from the perspective of the chamber, because hating what you have is the first step towards reparative consumption.

What he disparages in his parlour is amplified in the street and beyond. This is especially so when Crumpet, his wife and daughter are invited to the home of his recently married friend Mr Frippy, ‘whom,’ Crumpet observes, ‘five weeks ago I regarded as an extremely tasteful and elegant gentleman’.

Greeted by the joyful Mrs Frippy at the entrance to their villa, Crumpet politely abstains from mentioning the imitation rosewood door, the warty knocker or the porphyry-painted Ionic columns. When Frippy asks whether his decor ‘would pass muster at Marlborough House’, Crumpet delivers a lecture cribbed whole from the museum catalogue, addressing the importance of flatness, apt colour choice, seemly proportion, geometry and consistency of implied light source. Frippy concedes there is sense in some of Crumpet’s complaints, while also acknowledging that it’s all a bit too intrusive. While Frippy’s choice of clothes and furnishings show that he is exactly the right target for the museum’s program of improving taste, he’s uncowed by Crumpet – the shame just bounces off him.

Undeterred, Crumpet ramps up the pressure, observing that Frippy’s carpets could not possibly be walked on ‘without treading on half-a-dozen thorns, and perhaps dislocating my ankle among the architectural scrolls projecting out if it’. Carpets depicting objects that people would not routinely walk upon proved one of the chamber’s weirder complaints about lower-middle-class style, refusing to concede the absolutely essential differences between ornamental illustration, actual three-dimensional objects and the sheer banality of carpet-treading. Frippy agrees to give this some further thought, but as with his earlier responses, it’s clear that he won’t.

Despite being thoroughly rebuffed, Crumpet turns his critical eye inwards and the story concludes mostly as internal monologue. Tea arrives on a Landseer print tray – an actual item exhibited in the chamber made of papier-mâché and decorated with the artist’s portrait of a red deer stag, The Monarch of the Glen. Crumpet mentally runs through his checklist of catalogue-authorised objections to it: first, the picture is a piracy; second, it is pointless because the stag will be obscured by a teapot; third, the decorative scroll lines are hopelessly random;

‘fourth, the glitter of the mother-of-pearl is the most prominent feature of the whole, and being spread about, creates the impression that the article is slopped with water, or –’ finishing my cup of tea just at that time, I dropped my cup and saucer – to their utter destruction, I scarcely regret to say – with a cry of agony–

‘Papa, Papa, what is the matter?’ cried my child: and my wife ran to me, and Mrs Frippy, for I had fallen back in my chair almost deprived of reason.

‘A but–’ I gasped.

‘But what, my dear?’ asked my wife.

‘Butter – fly – inside my cup! Horr – horr – horr – ri – ble!’

Having failed to move Frippy towards reform, Crumpet takes a more direct approach to reshaping his interior. Where argument fails, gravity, aided by a moment of near-hallucinatory revulsion at the sight of a butterfly print in his teacup, effects a triumph of sorts. The cup is smashed to smithereens.

The pieces of Crumpet’s cup give emphatic shape to the feelings it provoked – disgust, inappropriateness and uselessness – in a form that renders these judgements inarguable. The breaking point, as it were, arrives as Crumpet’s verbal criticism becomes practical action. Of course, this is the hysterical culmination of Crumpet’s fixations; a man of the lower-middle classes, burdened, overreaching and finally buckling under the impossible demands of unfeeling taste elites (the invisible curators of the Chamber of Horrors) and thus embodying exactly the kind of implosion of character demanded by satire of this type. But take Crumpet and his dropped butterfly cup a little more seriously just for a moment.

The broken cup also opens a serious gap in the Frippy tea service, now incomplete and susceptible to the damaging impression of want. It will need to be replaced, necessitating a push outwards to the market and a choice: to restore the original or to reform as the chamber dictates. This teacup storm overrules Frippy’s polite, but firm, refusal to participate in museum judgements. In lieu of tea, there is sympathy for Crumpet’s distress. Frippy helps his weakened friend towards the door, buttoning his coat while explaining how he fears Crumpet has choked on the museum views swallowed whole, where they should have been quietly digested; to have done otherwise was to risk the very breakdown to which Crumpet has apparently succumbed.

Crumpet does clearly change by the end of the story, becoming something very different from that which Frippy, or the museum for that matter, might have imagined. As he splutters and gags at the sight of his butterfly teacup, his crisis reveals a sly victory. Faced with the offending cup, Crumpet does not for once recite the relevant lesson from the catalogue that actually reads as follows: ‘because utility would be better served by the absence of any decoration in the part which receives the viands, to satisfy that sense of cleanliness, only to be obtained by the white unchanged surface of the material’. He has reacted reflexively, as if suddenly he were an imperious tastemaker rather than parroting aesthetic principles learnt from a pamphlet. It is as if from this very moment that Crumpet (like Lady Gaga) was ‘born this way’, with no choice but to dash the vulgar cup to the floor, to demand something better and more beautiful in its place. Where the curators of the chamber may have conspired to shame the museum’s leisurely visitors into becoming better consumers, in Morley’s story they have instead inadvertently created an anguished aesthete whose taste is expressed through involuntary symptoms of teacup repugnance. Triggered in the chamber, refined in his home and finally driven inwards in Frippy’s parlour, Crumpet’s shame forms a new critical style detached from his conventional obligations to friends and family or the polite need for aesthetic consensus among the lower-middle classes. Crumpet exhibits, well, what else to call it but a queer sensibility – as yet not fully aligned with a sexual identity – that privileges style over comfortable familiarity, waspish judgement over the dead weight of respect owed to household possessions. By the end of Morley’s story, Crumpet has acquired a form of cultural authority, yet its expression is inseparable from paradox (his domestic style threatens anti-domesticity) and the appearance of excess (his emotional and embodied response to the cup) – conditions that continue to shape, and haunt, queer domestic expertise. Crumpet’s queer eye is, it seems fair to say, an unintended consequence of rational recreation and the shame it cultivated.

WHERE VICTORIANS FOCUSED their considerable shaming energies on ‘improving’ the working and lower-middle classes, our twenty-first-century equivalents have a wider social ambit and a looser, more provisional program of moral instruction. Consider the range of practices of which ‘holiday-makers’ – to choose but one jam-packed category of leisure-seekers behaving badly – find themselves accused: from the gravest systemic environmental despoliation at one end of the spectrum through to casually disgusting mid-flight toenail trimming at the other. If there is a midpoint here, I would suggest that it is, like the kind of examples with which I began, an attitude of disengagement or distraction from some greater, and ostensibly more enriching, view of, say, Barcelona’s La Sagrada Familia.

The British photographer Laurence Stephens takes such moments of slack-jawed phone-staring and sweat-soaked ennui as his urbane subject in Bored Tourists (2018), a comprehensive anthology of sneaky and unsympathetic leisure-shaming. Of course, here, the moment of judgement is, of necessity, virtual and belated, but no less in the service of some corrective impulse. It appears that the world is wasted on these holiday-makers and not, by extension, on us. But here is the problem: strip away the particulars of clueless or crass or simply preoccupied leisure, and the criticism – the directed shame – is one of mismanaged time. What is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life, asked the poet Mary Oliver. And the answer, one suspects, is not take phone meetings or play Minecraft in the Valley of the Kings. But then again, you are not supposed to play games at work either – there are real (and shameful) HR consequences for carving out pockets of unproductive leisure from the schedule of the working day. Today’s insidious leisure/shame nexus leaves us – rather like Crumpet – caught in a paradox, unable to escape the moral trap of recreation, whether at the museum or the beach.

Share article

About the author

David Ellison

David Ellison is a senior lecturer in literary studies and cultural history in the School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science at Griffith University....

More from this edition

Open water

FictionBrenda clasped her whistle as she waited. She had a special let camp begin call that only got used once a year. The newbies would learn quickly what Coach’s unique calls meant. Brenda contemplated if she would join in this year’s campfire singalong. With her whistle, she had been practising a rendition of ‘Eternal Flame’ by the Bangles. She knew the girls went wild for their coach’s dorky antics.

All the boys she ever loved

FictionWhen he left that night with Lacey on his arm, off to go bowling or something, he shook my hand and said Goodnight, David, like it was some big joke or something, and I said Goodnight, David back, and then he was gone and immediately after the door shut, Mel was on my back and saying: You can’t keep doing this, and when I just raised my bad hand up and looked at her, she said: Going so hard on them like that. It’s not doing our daughter any favours. I don’t know why you’re talking about this like it’s some sort of pattern. I’ve only ever got to meet two of them. And she said: Exactly.

The rise and decline of the shopping mall

FictionPerhaps it is instructive to consider how archaeologists of the future may conceive malls. How might they seem, these empty labyrinths – like rituals that had to be endured in order to receive goods and services? As great monoliths, colosseums constructed for our entertainment? As places of worship? Or perhaps malls will seem more like pyramids do to us: mysteries to be unravelled when the tracks of global trade and communication have faded...