Always was, always will be

Reimagining Australia’s past

Featured in

- Published 20240206

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-92-4

- Extent: 204pp

- Paperback, ePub, PDF, Kindle compatible

Since she began writing in the 1990s, multi-award-winning Goorie author Melissa Lucashenko has been flipping the script. With grit, defiance and killer one-liners, her novels relate the untold stories of Aboriginal Australians living ordinary lives. In the process, her work dismantles lazy stereotypes and exposes the realities of Australia’s colonial legacy.

Her latest novel, Edenglassie, moves between mid-nineteenth-century and contemporary Brisbane to interrogate the myths of the past and explore how they’ve shaped our present. In this conversation with Griffith Review Editor Carody Culver – which has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity – Melissa reflects on the challenges and possibilities of historical fiction and the writer’s role in helping us understand who we are.

CARODY CULVER: Your work explores class, colonialism, structural injustice and racism: themes that anyone who’s paying attention should recognise as part of the fabric of everyday life in Australia. What role do you think fiction plays in making people engage with and understand those realities?

MELISSA LUCASHENKO: I think fiction can be incredibly powerful for certain individuals. On a social level the literary novel is a niche market, but what’s happened – encouragingly for literary novelists – is that our work is now sometimes [turned into] audiobooks, film and television. I can get a bit despondent about the state of the world – you know, what’s the point of writing books? – and then I pick up something like Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead and I just think, wow. There’s such power in the right book at the right time, and that gives me a prod to keep going. And the feedback I get from my own work is encouraging, too. I guess everyone has to do a bit, and taken altogether the [power] of literary fiction to improve lives and to bring joy and to shed light on unseen worlds is, I think, extraordinary.

CC: In an interview you did about ten years ago, after your 2013 novel Mullumbimby came out, you said: ‘Poverty is not the historic norm for Aboriginal people. We have been here for 60,000 years, and for 200 of those we have been marginalised and poor, but it is not our normal condition. One day we will be managing our own affairs and we will be living the good life and that is what I wanted to point to in [Mullumbimby].’ Do you still feel that way?

ML: Yep, I do. It’s a simple fact that we’ve only been marginalised since some time into the British occupation, and the fact that that didn’t happen immediately is what I was trying to get at in Edenglassie. Colonisation is an ongoing process, but that doesn’t mean it has to last forever, and I think one day we’ll have treaty. I don’t know how long it will take, but we’ll have reparations and we’ll be recognised for the knowledge and the skill that we have in living in this place, and that will be to everyone’s benefit.

CC: There’s a powerful sense of what-if in both Edenglassie storylines: before we first meet your historical protagonist, Mulanyin, one of the other characters in that nineteenth-century timeline is predicting that the English will leave soon and things will go back to the way they should be; when we first meet one of your contemporary protagonists, Winona, in 2024, she’s fantasising about a better life for herself in a more just and fair Australia. It’s a tying together of past, present and future, as though you’re drawing a line from the injustices of history to an eventual time when those injustices aren’t forgotten, but when life is good again.

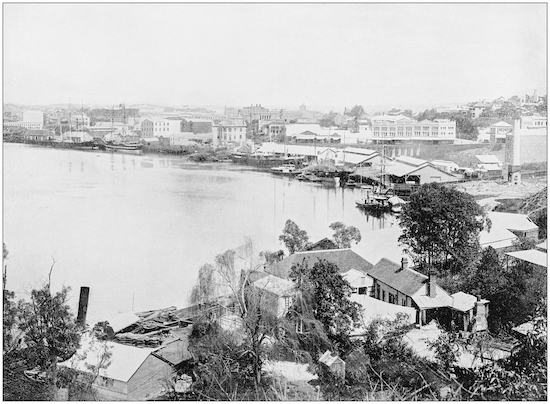

ML: What I was driving at in Edenglassie was what happened one generation after invasion: what life was like, what Brisbane was like, who was doing what. I’ve been fascinated by that for decades, and I think all Aboriginal people walk around and drive around and get around with a constant lens of pre-invasion as well as what’s here now. When we look at a landscape, we’re very often thinking, Well, take away the buildings, take away the roads, take away this kind of civilisation – so called – and what would have been here in our great-grandparents’ and great-great-grandparents’ time? So that was the key question I wanted to explore for my own curiosity as well as for the sake of a narrative. I wasn’t looking very far past what it was like in colonial Brisbane when colonists were just about to outnumber Aboriginal people for the first time. And then that seam of: we’re still here – what are our lives like now? How are they influenced by history? I wasn’t looking very far into the future; I think that was a bit beyond the scope of the book. But certainly there’s love and there’s joy and there’s laughter as well as all the hard stuff going forward from the 2024 narrative.

CC: Do you think there are differences in how contemporary fiction and historical fiction can make us reconsider or reframe the past and the present?

ML: I probably wouldn’t have written a historical novel if I didn’t think so. We live in a world of instants – what’s the latest post on social media? What’s the latest sound grab? ‘The continuous now’, I think someone called it, and not in the good sense. As an Indigenous person, it’s a quest to understand where you live. In traditional society, as I point to in the book, you’re taken around your country, you’re shown particular things, and you don’t leave your country except briefly for ceremonial [reasons] or perhaps to marry. And so you understand that country more intimately than almost any modern person can understand where they live. I think that’s what ultimately drove me to write historical fiction. I was born in Brisbane. I’ve lived most of my life here apart from a decade down on Bundjalung country, which I return to just about every weekend. But Brisbane calls to me, and the story of Brisbane called to me, and so it felt like a real quest to understand the place better. [I had] this intense curiosity about the process of colonisation, especially on the south side, and what that looked like and how people would have experienced that, and I found enough stories to fill three or four historical novels. The untold stories are manifold – there’s thousands.

CC: Did you always intend to have a contemporary storyline alongside the historical?

ML: No. I had planned to write a historical novel of colonial Brisbane for a good twenty years and almost started it in the mid-’90s; I’m really glad I didn’t because I’ve written a far superior novel to what it would have been back then, when I was younger and even more ignorant than I am now. Edenglassie was going to be a straight historical novel, and then I realised the constant thorn in my side as a First Nations writer: the spectre of the dying-race trope was not going to go away in my lifetime nor in this novel’s lifetime. And so there had to be a through-line to show Aboriginal continuity, Aboriginal life and love in the present, simply because that trope of the dying race and the vanishing of culture is so strong. It would have been too easy to write a historical novel and have mainstream readers misinterpret it as an elegy for an Aboriginal world view that’s no more. I’ve never set out to do that, but people interpret my work in that way sometimes because that’s the yarn that’s been around for most of the past 200-odd years now.

CC: Why is it such a persistent trope?

ML: Because it’s convenient. There’s an element of truth: many, many thousands of people died. The numbers of people who died on the Queensland frontier are just mind-boggling to the point where I’m sure huge numbers of people won’t believe the figures I refer to in the back of the book. But that’s the job of historians, not the job of novelists, to prove and disprove those figures. If Aboriginal people are all dead, you don’t have to negotiate a treaty with us and you certainly don’t have to go around feeling guilty about stolen land and stolen wages and stolen children; the subjects of that injustice don’t exist anymore if you choose to believe that we’re dead or all assimilated, which isn’t the case. It’s a very practical kind of assimilation strategy.

CC: Were there other tropes or ideas that you wanted to push against or that you felt historical fiction would be a good means of addressing?

ML: No, I think it was a big enough job just to push back against the wonderful British civilisation arriving in darkest Jagera land, but I tried to flip things a lot. I like to surprise my reader, I like to play with duality, and that’s a cultural motif from classical Aboriginal culture that I’ve tried to implement in the book – sometimes consciously and sometimes unconsciously. You don’t always know what you’re doing with a novel – you can sit and talk into a microphone and make out like you always know why the character did such and such in the first chapter and then did the reverse in the final chapter. You might have one explanation for that and then six months later you’ll sit up in bed at night and go, ‘Oh, that’s what that was actually about.’ So you try to be as strategic as you can while you’re stumbling through the lives of these characters you’ve invented but don’t necessarily fully understand.

The contemporary storyline was easier to write because it’s easier to imagine Blakfellas getting around South Brisbane in 2024 than it is in 1855, and also my main character in the colonial era is a teenage young man, not an elderly Aboriginal woman and her granddaughter. I had that twin challenge of drawing on lots of research, oral and written, imagining myself into the 1850s, and also trying to invent a character who’s a young man with very limited exposure to white society, almost no exposure to Christianity, who’s thinking and living and acting in a tribal way. That was hard, but I worked my guts out for four years and just about exhausted myself… When I handed in the final manuscript, I just went, ‘I really don’t know how the hell I wrote that book.’

CC: Well, I’m glad you did! But it must have been a very different writing experience – as you say, you had all that research, those untold stories, to weave into the narrative.

ML: And [I was] trying to make decisions all the time about the right way to portray Mulanyin and the right way to portray [his wife] Nita. I was always conscious of the way mainstream readers were going to approach these characters and trying to second-guess that and head things off at the pass. I have to do that in all my writing, but I had to do it to a different degree in this historical book [because of] the twists and turns of history and what actually happened here.

There are fascinating snippets I found early on in my research. The novel centres on the interaction of a pioneer white family, the Petries, and the Jagera people who live at what I’ve called Kurilpa Village at South Brisbane – almost exactly where we’re sitting right now [the Griffith Review office in South Bank]. In the literature, I came across the fact that [Tom] Petrie’s Aboriginal workmen at Murrumba Downs had ‘P’ branded into their arms to identify them as his workmen. I reflected on that, and then I was talking to Gaja Kerry Charlton [about it] and she pointed to her forearm and said, ‘Yes, our family had “P” on us.’… That was actually something that the men requested, and that kind of flips the story on its head – rather than being branded semi-slaves, these men wanted to be identified with Petrie. And then you take that a step further, and as a novelist you ask, is it about a kind of tribal affiliation, that they be known as Petrie’s men? Is it because they’re proud to work for Petrie, or is it a safety thing, so that when they’re walking around or getting around the countryside – which was contested country until the 1860s and, in some areas, the 1870s – they could say, ‘Look, I belong to the Petrie property, and therefore if you harm me, if you shoot me or do anything to me, you’ll have the Petries to answer to’? I don’t know the answer, but that’s the kind of process I had to go through hundreds and hundreds of times with all these historical facts and situations.

CC: You said that you’re always having to think about how mainstream readers might receive your work, and I wondered if you could talk more about that. In Edenglassie’s historical storyline, there’s terrible violence and a constant sense of uncertainty and threat, but your characters are also just living their lives, and that’s the case in all your books – you don’t shy away from the tough stuff, but you also want to show joy and laughter.

ML: On a simple writing level, if a book doesn’t have love and humour and lightness in it, it’s probably going to fail as a novel. As Bruce Pascoe said – no one asked Faulkner if he could include more humour. But we’re not William Faulkner and it’s not 1860 or whenever the hell he was writing. So there’s the simple craft of writing a book that people are going to want to read and get some enjoyment from. It’s not all about telling historical truths, or if it is it’s about showing the whole historical truth.

On a second level, it’s a political act to write Aboriginal people or any marginalised people as fully human, and that’s probably [how] I’d sum up the second half of my writing career… The first half was, ‘We exist, we’re still here. Aboriginal people have not died out or mysteriously gone away, conveniently, for white powerbrokers.’ There’s some understanding of that now, especially since native title has people frothing at the mouth about living Aboriginal people everywhere. So we’re fully human, we fall in love, we fall out of love. We observe white society at least as often and as keenly as white society observes us.

CC: You mentioned duality earlier, and one of the other things I love about the book is how you weave opposing viewpoints into the narrative. There’s a great chapter in the contemporary storyline where a character reveals that he’s not white – he’s recently discovered that he has an Aboriginal ancestor. But when he tells Winona this, she says, ‘Hang on, buddy. This doesn’t mean that you get to call yourself Black.’ This is interesting in terms of how people understand their identity – if you make this kind of discovery about your heritage, you might be tempted to lay claim to a past that you perhaps don’t fully understand.

ML: As I wrote in The Monthly recently, that’s a serious problem – Aboriginal culture is vulnerable to damage by people who unilaterally decide that they want to identify [as Aboriginal] but don’t know what that means and don’t know how that affects the core Aboriginal culture. There aren’t any easy answers, and I wanted to show both sides of that. So [there’s a scene with] a white didge player who’s fraudulently pretending to be Aboriginal and is quite uninterested in Winona’s opinion of him – he couldn’t give a rat’s arse that this Aboriginal woman thinks he’s a fraud, and so she picks the didge up and tries to belt him with it. And again, that’s my little flipping of the thing that women can’t touch a didgeridoo – I’m playing with that because culturally it’s not 100 per cent accurate. And I wanted to show that there are different ways of being Aboriginal and there are ways to become Aboriginal, but it’s not as simple as just declaring that you are – that’s not the way to go.

CC: You describe the novel’s title, Edenglassie, as ‘a nod to paths not taken’. Could you talk about that idea?

ML: I’m writing about a place. I’m writing about the story and stories that belong to this particular place, around about where we’re sitting now, in South Brisbane. And I really love the word – it’s got the word ‘Eden’ in it, which I particularly liked because I think this place would have been an Eden before Oxley sailed up the river and commenced to wreck it all, and it’s got ‘lassie’ in it. As a feminist writer I like the fact that it’s got ‘Eden’ and ‘lassie’.

In terms of paths not taken, I couldn’t call my book Magandjin or Meanjin, which was my initial thought, because firstly I hadn’t sought permission at that stage and I didn’t know if I would get it, and second, I wasn’t writing about the place as it was before colonisation. I think that’s a task that’s beyond most people and certainly beyond me. I couldn’t call it Brisbane because it’s not about Brisbane – it’s about a place that wasn’t Magandjin, Meanjin, it wasn’t Brisbane, it was an in-between kind of place. Again, it’s at that tipping point – it’s something else. So when I discovered that an early colonial name for Brisbane was Edenglassie, but the name didn’t stick, I thought, aha! That’s perfect because it just instantly says to the reader, Brisbane didn’t have to be Brisbane, it could have been this other place. It could have been Edenglassie, and what would that have looked like? What would it have looked like if every colonist had done what Petrie did and sought permission to settle where they did? Of course, we’ll never know. So it was a glimpse into a future that could have been but never was, and that’s why I used the name.

CC: When your novel Too Much Lip came out in 2018, Karen Wyld wrote a review in the Sydney Review of Books that references a keynote speech you gave at the FNAWN Conference that year in which you (in Wyld’s words) ‘challenged participants to unpack sovereignty and reconstruct it in our way. [You] encouraged First Nations writers and storytellers to reshape and share who we were before invasion, are now, and will be.’ Could you talk about that in the context of Edenglassie – was this part of your thinking as you were researching and writing the book?

ML: The book is very much about how I understand classical Goorie culture in Jagera lands, and sovereignty is just automatically part of that. As the Old Man says in the opening pages, we’ll have our lives back when these last few British convicts leave; we’ll have a sane world where people don’t go around calling each other ‘master’. And he almost spits when he has to say the word ‘master’ because it’s such a foreign and abhorrent term to him.

Sovereignty is problematic – I think people use it as a shorthand for power, but the legal definition would be different, and then the cultural definition is different again. I think as much as I’m writing about sovereignty I’m writing about what Wiradjuri people call yindyamarra and what Yolngu people call magaya, which is a state of civilisation where people behave lawfully, slowly, politely, respectfully. Where a state of peace exists and there’s little dissent or trouble and people are free to lead good lives in a world that’s worth living in. That’s the world I wanted to portray as being lost, or almost lost, in 1855, alongside a vision of a future that [my contemporary characters] can strive towards in 2024.

Image credit: Getty Images

Share article

More from author

On ‘The Seven Stages of Grieving’, by Wesley Enoch and Deborah Mailman

GR Online IS IT POSSIBLE to feel too much? For millennia, stories from around the world have had as their explicit task the expansion of the...

More from this edition

Which way, Western artist?

Non-fiction Michael Zavros, Bad Dad 2013, oil on canvas, 110 x 150 cm INSIDE YOU THERE are two wolves. Their names are Mark Fisher and Camille...

Escaping the frame

In ConversationAll my work as a writer and activist over the last fifty years has comprised various attempts at what I call ‘escaping the frame of European colonisation, European story and European ways of telling story’.

The sentimentalist

In ConversationI’ve positioned myself as somebody who’s constantly going through the trash of yesteryear with my raccoon paws and saying, ‘Wasn’t it grand?’ I think it’s more that I’m drawn to things I misunderstood rather than things that are just old, and I’m also interested in diagnosing the culture through what we loved, what we made and what we despised. It’s becoming much more clear to me the older I get.