Featured in

- Published 20151103

- ISBN: 978-1- 922182-91-3

- Extent: 264 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

‘CIVILISATION OFFICIALLY ENDED today,’ the ever-pithy Jane Caro tweeted forty-eight hours before Anzac Day 2015.

She was not referring to the looming centenary commemoration of the tragedy on the Gallipoli Peninsula, which we have been urged to believe made Australia a nation, but the closure of an elegant, expansive bookstore. She was upset that Watermark Bookshop, for several years a welcome addition to the shopping mall that doubles as the Qantas Sydney airport terminal, was being replaced by a store selling make-up and perfume.

The bookshop was just a dot at the bottom of the Asia Pacific division of Lagardère, the vast French conglomerate that grew from an 1826 Parisian bookshop and now focuses on ‘content, audience and networks’. Despite the suggestive logic of vertical integration, the global owner of the bookshop opted out, although it still owns Newslink, the convenience stores akin to information fast-food outlets. High rents, low margins and airline strategic priorities were suggested to be the reasons. Jane Caro and her Twitter followers were incandescent with disappointment.

Not long afterwards, another division of Lagardère announced the closure of its bookstore at Kings Cross railway station in London and the abandonment of plans to build a network of bookshops at airports and railway stations around the world. This is a global business and the rules of business prevail.

Lagardère owns Hachette, which has a strong presence in Australia, and is the third largest book publisher in the world. It is the dominant French media company, with vast interests in global sport, Airbus and Virgin Stores, and countless other enterprises. It will no doubt develop another strategy – there is money to be made from matching content with audiences.

The absence of the expansive bookshop is acutely felt, especially by those of us who, like Jane Caro, spend a lot of our lives getting to and from planes, a book the perfect travelling companion.

IT WOULD BE unwise to read too much into the closure of this particular bookshop, although it is not the only one that closed this year. Bookselling has been somewhat precarious for a decade. It has endured a lot of changes as the forces that are transforming other cultural industries – technology, globalisation, corporate aggregation and changing consumption habits – take their toll.

But each time a bookshop closes there is one less place for a reader to find something that will take them to another world, inform or entertain them. When a chain of bookshops closes it ricochets through the industry with impacts on publishers, printers and authors. Over time this affects the resilience of society itself because the public sense-making that books provide lie at its cultural core.

Last year, Australians spent just under a billion dollars on (paper) books, plus more on virtual books, audio books and imported books. Just over a quarter of the books sold in Australian shops were novels, about half were non-fiction and the remainder books for children and young adults. The gap between the bestselling titles and the rest is greater than ever as the global publicity juggernaut relentlessly focuses on one title at a time – this week Harper Lee, then Jonathan Franzen, then the Man Booker winner…

Despite the passing sales hype, literature has been one of the bedrocks of cultural expression for millennia. It is not flashy, it takes time to create and needs to be supported if the civilisation Jane Caro and countless others hold dear is to thrive. The product can not only change individual minds, but collectively define us to ourselves.

Breaking through is hard, and there is a temptation to allow the winner to take all. Successful writing is, however, like all the creative arts, almost never achieved alone, even if the image of the writer in a garret who drops into the festival publicity circuit every couple of years comes most readily to mind.

Writing may be a solitary occupation, but it is supported by networks of other writers; by parents who inspire children to read and imagine; by teachers who encourage writing and research; by editors who draw out the best in a work; by journals that enable authors to experiment and find new readers; by publishers who put resources and expertise into creating beautiful objects and building markets; by critics who share and add depth, pushing for the next level of excellence; by prize judges who painstakingly read and assess; by booksellers who display and sell; and by readers who go the extra mile to respond, reflect and encourage.

For every successful book there are dozens that deserve to achieve similar fame, but for a random range of reasons fail to reach the audience who would take it to their heart. Word-of-mouth is good and, with a billion people connected on Facebook alone, more powerful than ever, but not a failsafe.

THE ECONOMICS OF this are surprisingly fragile and interconnected, especially in English-language countries with small populations, such as Australia and New Zealand. It has never been easier to access the best the world has to offer and enjoy, reflect on and learn from it.

But this is not enough. Even in a globalised world everyone comes from somewhere – the local remains important and understanding, analysing and describing that demands local support so that writers can perfect their craft and help make sense of the here and now.

Over the past forty years the Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) has refined an exceptional model to help achieve this, returning a small levy on the non-commercial distribution of writing to the creators of the work. Eight years ago, under the founding chairmanship of Brian Johns AO, CAL developed a Cultural Fund to expand this role, and has provided $16 million towards supporting the development of original creative works.

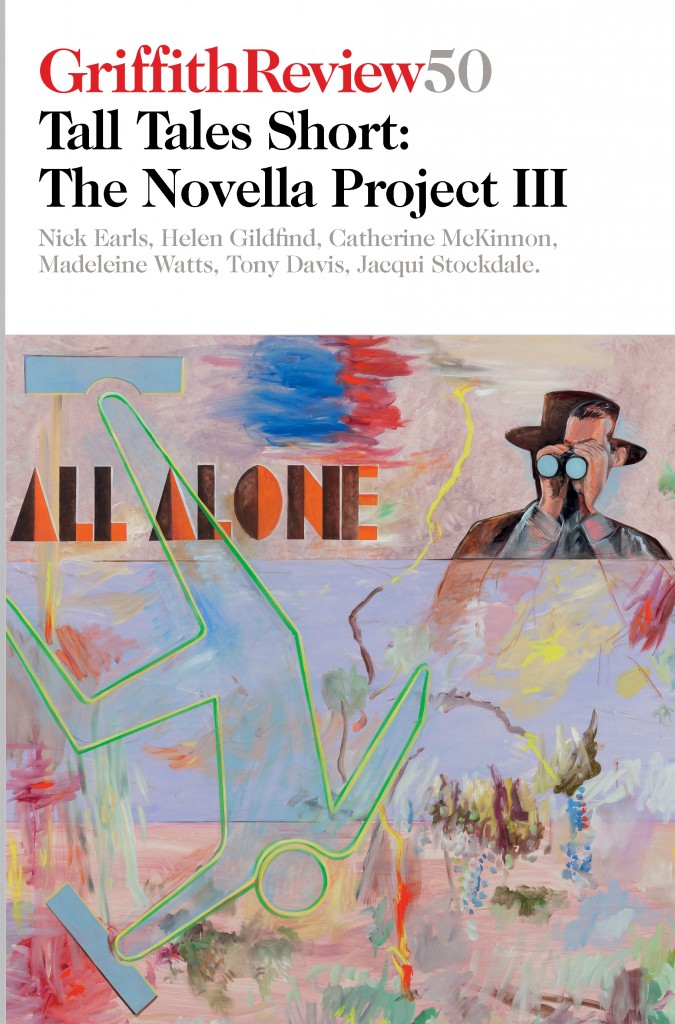

This is the third time that CAL has supported The Novella Project, and this year we were privileged to have Brian Johns, who was once a distinguished publisher of Penguin Australia, as one of the judges. He was joined in this rewarding, but demanding, task by author Cate Kennedy and editor Jacqueline Blanchard.

Brian’s commitment to fostering the expression of unique Australian stories in literature, art and screen is unrivalled, and this volume is dedicated to him and his enduring contribution to this civilisation.

Share article

More from author

Move very fast and break many things

EssayWHEN FACEBOOK TURNED ten in 2014, Mark Zuckerberg, the founder and nerdish face of the social network, announced that its motto would cease to...

More from this edition

Afraid of waking it

FictionHE SET THE camera up by the wall in the space he used as his studio. It was one of the many rooms in...

Papercuts and bloodlines

Will Martin

FictionMY OAR STABS the side of the Reliance. We push off and pull away from the ship. Venus is out, but the sky still has some light. Mr Bass and I boat the oars and hoist sail. The Lieutenant takes the helm. Tom Thumb’s sail snaps at the breeze and air-filled we bounce across the water.‘To dare is to do!’ Mr Bass shouts our motto.‘To dare is to do!’ The Lieutenant and I reply as if we are one.Seawater sprays across the gunwale. It is Thursday, the twenty-fourth of March, the year 1796. This is the day that we embark on our second Tom Thumb sail.