Featured in

- Published 20250506

- ISBN: 978-1-923213-07-4

- Extent: 196 pp

- Paperback, ebook, PDF

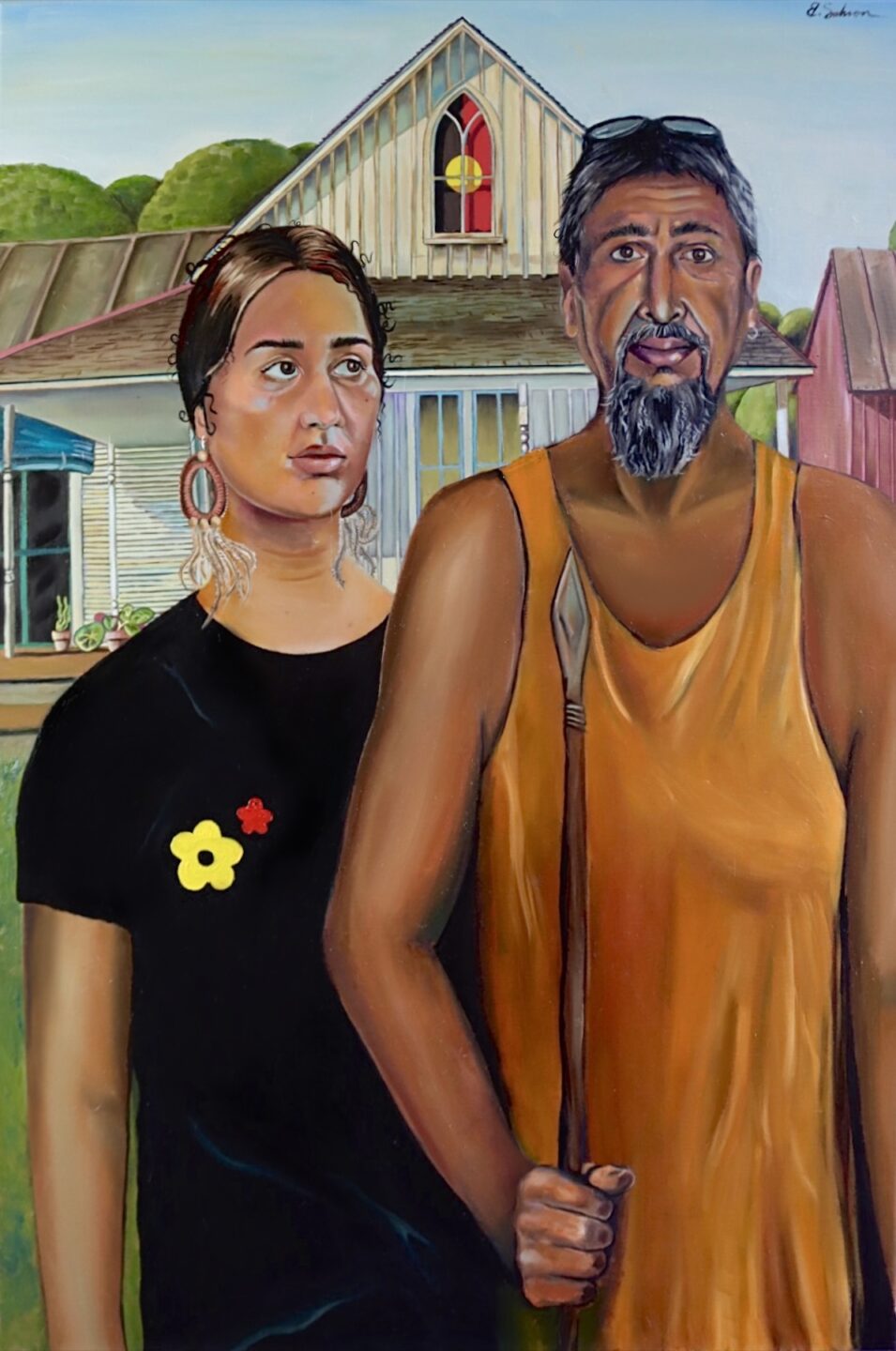

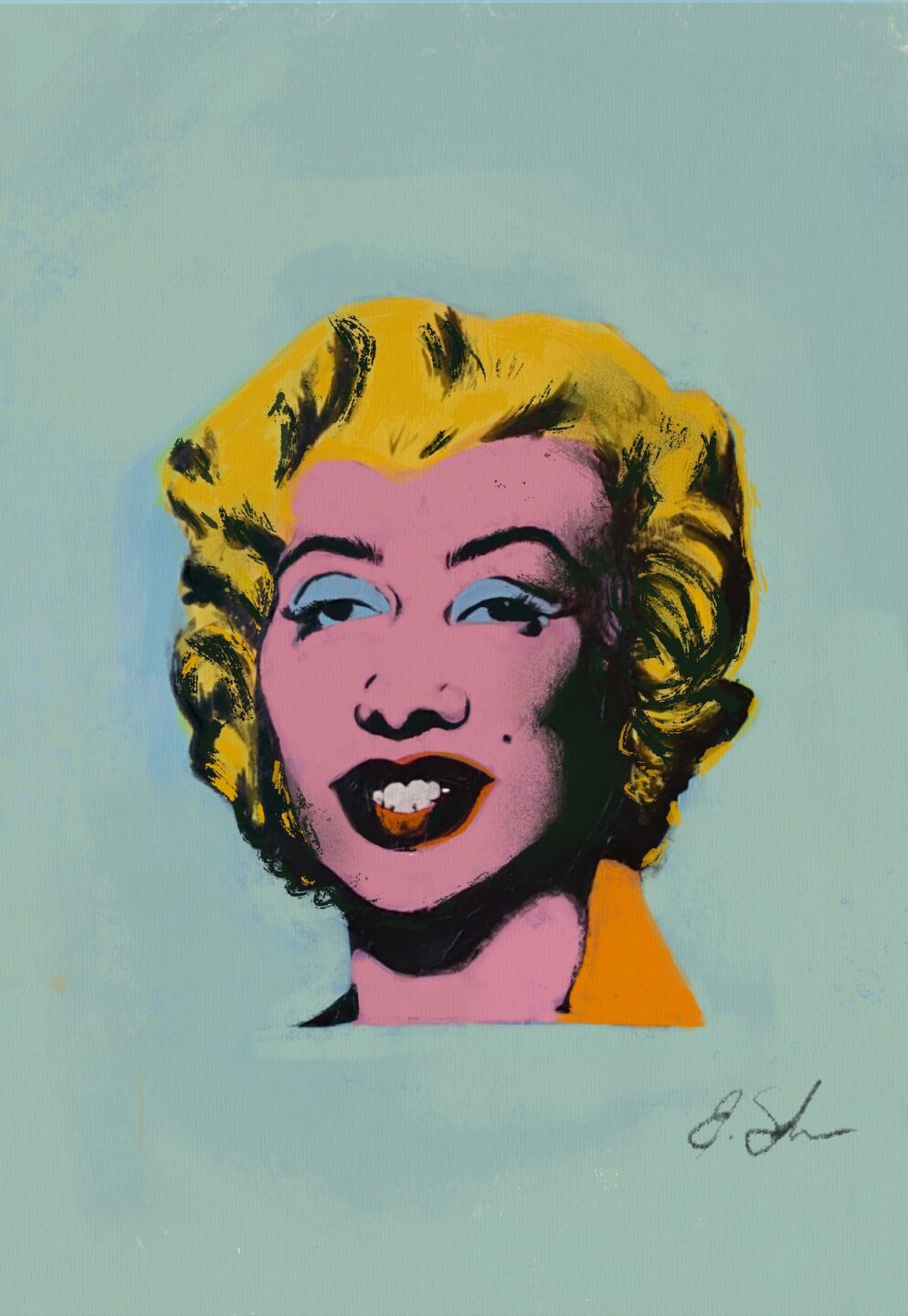

When Brandi Salmon taught herself to paint as a teenager in country Victoria, she never imagined she’d grow up to be a full-time visual artist. A proud Wiradjuri and Tongan woman, Salmon went on to study creative arts at university, where she was struck by the limited ways in which Aboriginal people had been depicted in classic paintings. When an undergraduate assignment led her to reimagine Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus with a Blak woman at its centre, she realised she was onto something. Venus became the start of Salmon’s Aunty Collection: reimagined versions of famous paintings that feature Aboriginal women as their subjects. In this conversation, which has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity, she talks to Griffith Review Editor Carody Culver about flipping the script on representation.

CARODY CULVER: I’ve read that you initially taught yourself how to paint by watching YouTube tutorials when you were a teenager. What drew you to start experimenting with visual art, and how did you develop your style in this early period?

BRANDI SALMON: The thing that drew me to art is really hard to explain – why does anyone start making art? I was homeschooled and I had a lot of time on my hands, so I just was kind of giving everything a go.

I watched a documentary on Rembrandt and loved it – I love his work, the way he paints shadow, that really stark contrast, and I was like, ‘Wow, that’s painting – I want to give it a go.’ So I started painting by teaching myself, as you said, via YouTube, and I just became addicted. I loved that I could create something out of nothing, if that makes sense. And growing up, we didn’t have a lot of money – I was raised by a single mum and I have seven siblings – so oil painting wasn’t something I ever saw myself doing because I always thought, ‘That’s what rich people do!’ Just the fact that I was able to pull it off really interested me and kept me going. So then I studied art at university – I graduated in 2020 and now I’m doing a Master of Fine Art at Monash.

CC: Is that changing your practice in any significant ways?

BS: Definitely. I’m studying through Wominjeka Djeembana Indigenous research lab, and the way they’re teaching me is that my lived experience can be put into my research – that it’s actually valid as a research method, which is really cool because I was always taught ‘don’t be biased, be objective’. When I first did my assignment for the master’s, I wrote a whole thing about why I’m a bit biased and then my supervisor said, ‘You know, you didn’t have to write that – your lived experience can be counted.’ It’s really changed my way of thinking.

CC: Since graduating from your first degree, you’ve become known for your incredible Aunty Collection: Aunt Venus and many more. I’d love to know the story behind these paintings – what inspired them?

BS: [They came about] because I had this assignment at university when I was doing my creative arts degree. A lot of the time, art students will copy the old masters to get better at painting and fix their technique. So I thought, I’m going to give this a go and copy Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus – and while I’m at it, I’m just going to make Venus brown and make her look like someone I know. I didn’t really have words at the time to say why I was doing that – I was just drawn to it.

That was almost ten years ago – I’ve continued to [create those paintings], and now I have more words to explain why. When I was doing my degree, I saw a lack of Aboriginal people being depicted in paintings in a positive light. Say I had an assignment and I had to look up work by Aboriginal artists – it was mainly traditional art [with a few exceptions], like Gordon Bennett and Vernon Ah Kee, but nothing that I felt really represented me as a young Aboriginal girl who didn’t grow up on Country. So I tried to find a way to connect to Culture, but I wasn’t taught how to do traditional Aboriginal art, dot painting or Wiradjuri painting, so I thought, ‘This [re-creation of famous works] will be my style.’

My master’s is based on the Aunty Collection and the ideas behind it. It delves into the history of how Aboriginal people have been represented: what creates a representation of someone, what goes into it, how society responds and how that shapes the way we’re seen today.

CC: Can you tell me about some of the responses you’ve had from viewers to your Aunty Collection?

BS: It’s been mainly positive, especially from Aboriginal women and Aboriginal people in general. The work has got humour, and blakfellas, I think most of us are pretty funny – things don’t have to be so serious.

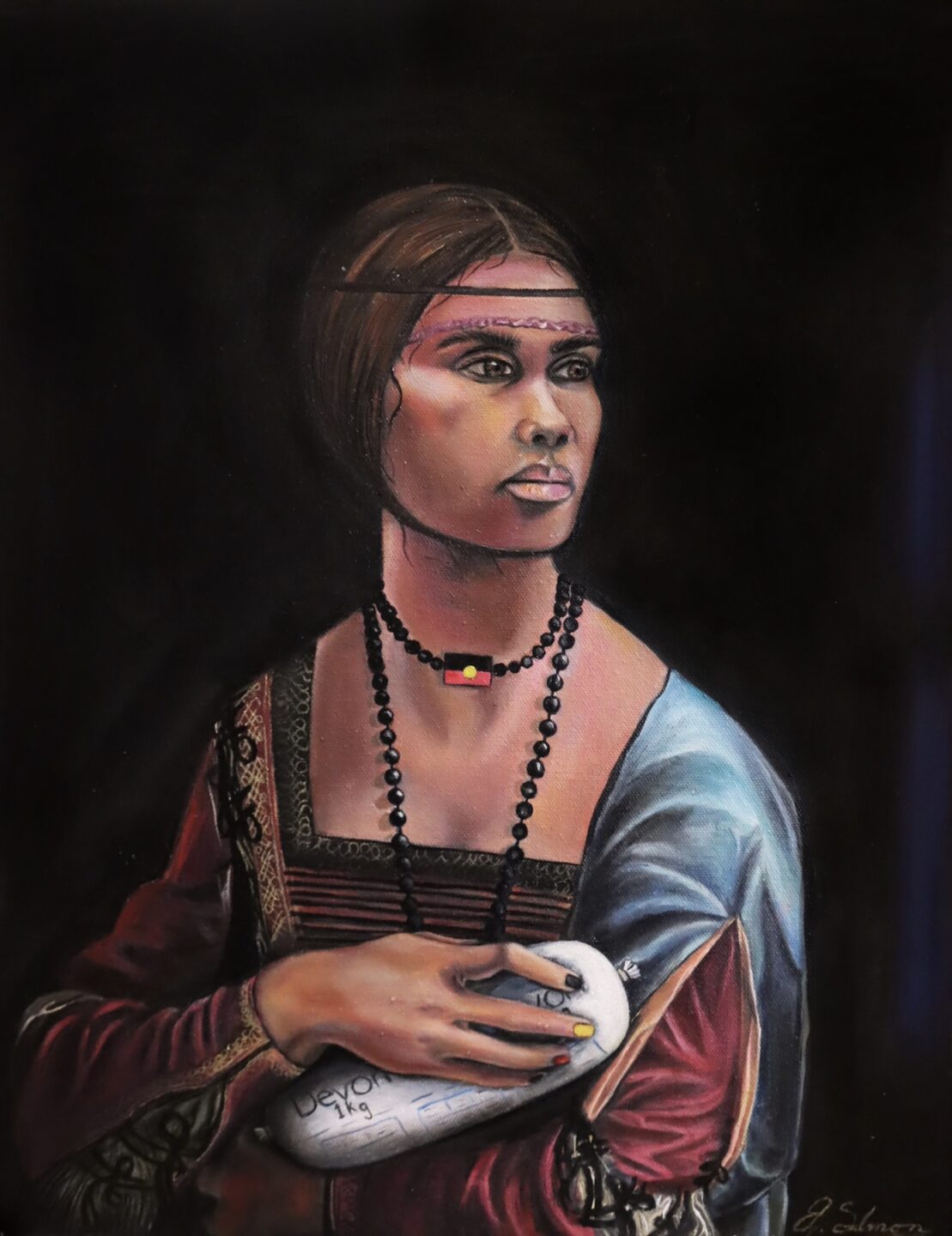

CC: One of my favourites in the series is Aunty with Devon, which is a re-creation of da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine in which an Aunty holds a log of devon lunch meat instead of a small furry animal…

BS: That one, I love it! I grew up on devon, and I wanted that to be an inside joke. Some people see that one and they’re like, ‘Ah!’

The responses have been really cool. We all know the Mona Lisa, we all know Girl with a Pearl Earring – I’m not trying to replace them, I see my versions slightly as parodies, but…I wanted young Aboriginal artists especially to come across my work and realise, oh, that’s not traditional art, the kind of art people assume all Aboriginal artists make – we tend to get put in these boxes. One girl put my Aunty Venus on a T-shirt and wore it when she went to the Uffizi and saw Botticelli’s Venus. So the paintings have kind of taken on a life of their own – they’re just out in the world now!

CC: What is it about the figure of the Aunty in particular that you wanted to explore artistically?

BS: My dad was adopted into a white family, so there was a loss of Culture for me and my siblings when we were growing up. I didn’t have that traditional Aunty figure a lot of the time, and if I did, they weren’t related to me. So in a way I was creating my own Aunties. I wanted to create these strong female characters in my paintings – some of them are people I know, some of them are just made up. And that feeling of having an Aunty – it’s really comforting! When your Aunty says, ‘Come here, bub, make me a cuppa,’ you feel so nice and warm inside. I wanted to put that feeling into the paintings.

CC: It’s interesting you say that because Vermeer’s subject in Girl with a Pearl Earring has this piercing gaze that seems to follow you, and it feels impossible to look away – I’ve always found it a bit unsettling! But your Aunty conveys a sense of comfort and safety with her gaze, as though she’s watching over you.

BS: That’s what I wanted.

CC: You mentioned before that people can make certain assumptions about Aboriginal art and about the kind of work Aboriginal artists create. Related to this is a fascinating post you made on Instagram last year about something you call the ‘Dollar Dot’ phenomenon – can you tell me about this and why you wanted to draw attention to it?

BS: I’ve noticed an influx of people who have been making a lot of money doing things like dot paintings when they’re not even from that mob. I feel very strongly about it because it’s not that hard to just…not do that! For me, I just steer clear of my own mob’s stuff because I was never taught that or given permission to do it – it’s one thing to learn but another to profit off it.

Often when I tell people I’m a painter they say, ‘Oh, then you do dots, right?’ And I’ve been asked, ‘Can you teach people how to do dot paintings?’ So it’s always been a theme in my career – oh, you’re an artist, this is the kind of art you must do. That’s why I made that post, because it’s becoming quite a trend, and when you call people out on it they can get very defensive – there isn’t any real, deep listening, which there’s usually supposed to be.

CC: You’ve also worked as a paralegal and a family violence practitioner, and you’ve got a strong interest in social justice – you recently created a beautiful painting of Cleveland Dodd, a sixteen-year-old Aboriginal boy who died in custody in 2023. How would you describe the relationship between your social justice experience and your visual art?

BS: They connect in so many ways. I worked as a paralegal for about two years at a Family Violence Prevention Legal Service, and it really opened my eyes. I was nineteen or twenty and I’d grown up in these white communities, and this place was in Mildura, which has a large population of Aboriginal people. The amount of racism I saw was insane. I experienced so much racism there, and I was only young so it really took a toll on me. I thought, this is wrong, I need to try to do something. I actually started studying law for a year, but then I realised, I’m not good at this, I can’t do this! So then I thought, I’ll make art in a way that will hopefully help people.

CC: Art and creativity are such fruitful ways of drawing attention to these issues, or making us think about them from a different perspective. You run your own business now, Brandi Salmon Art, through which you sell your original paintings plus prints and merch. What prompted you to strike out on your own?

BS: In 2020, during lockdown, I would paint in my lounge room just for fun. It always felt a bit too shame-job to try selling my paintings, and then I was approached to put Aunt Venus on a T-shirt. I didn’t even have an ABN, I had to create one especially! But I thought, I’ll never be able to start a business – it’s really scary putting yourself out there and being so vulnerable. But my partner said, give it a go and see what happens, you can do it. So I did, and then I became obsessed – I was painting every day, like five hours a day after work, and I was still working full-time. I didn’t have a studio or anything, I was still painting in the lounge room, and then I realised, ‘I need to make this a thing for the rest of my life – how am I going to do that? I just need to paint my arse off and then quit my job,’ which I did, and that was four years ago. It’s crazy, but it’s the best thing I ever did.

Share article

About the author

Brandi Salmon

Brandi Salmon is a proud Wiradjuri Artist living and working on Palawa Country in Lutruwita (Tasmania). She explores her Culture within her creative practice...

More from this edition

Scrolling to the end

IntroductionOur contemporary content malaise feels very recent, yet the twentieth-century media scholars Marshall McLuhan and Neil Postman predicted our technological capture decades before Mark Zuckerberg and his college roommates devised a neat way for their fellow Harvard students to connect online.

Resisting the ‘Content Mindset’

Non-fictionWhen we hear publishers, broadcasters or gallerists describing creative work as content, we know immediately that their approach is transactional. When we hear people describe their own work as content, they have already become complicit in their own exploitation. Social media profiles the world over feature bios identifying their owners as ‘content creators’: people who produce interchangeable matter to fill someone else’s space. Social media accounts are available free of charge on the basis that we will keep creating the work that feeds and evolves the algorithm, provides a culturally authentic context for ad placement and keeps us all scrolling – our number-one self-selected addictive behaviour.

Less than human

Non-fictionWhat elevates Miku and makes her significant in our cultural landscape is her accessibility. Unlike traditional celebrities, who, even if they want to be accessible to their fans, only have so much time and can’t be perpetually available, Miku is software that anyone can buy and use. It only costs $200 and doesn’t require particularly advanced technical skills. Most of the people who produce Miku music are self-taught. One of the enduringly popular things about the concerts is that everything you see essentially comes from fans – the music, costuming and dance routines are all drawn from the expansive ‘Miku community’, where the lines between amateur and professional are deliberately blurred by everyone involved. You’re as likely to hear a song produced through a record label as you are one that was popularised by YouTube.