Featured in

- Published 20210504

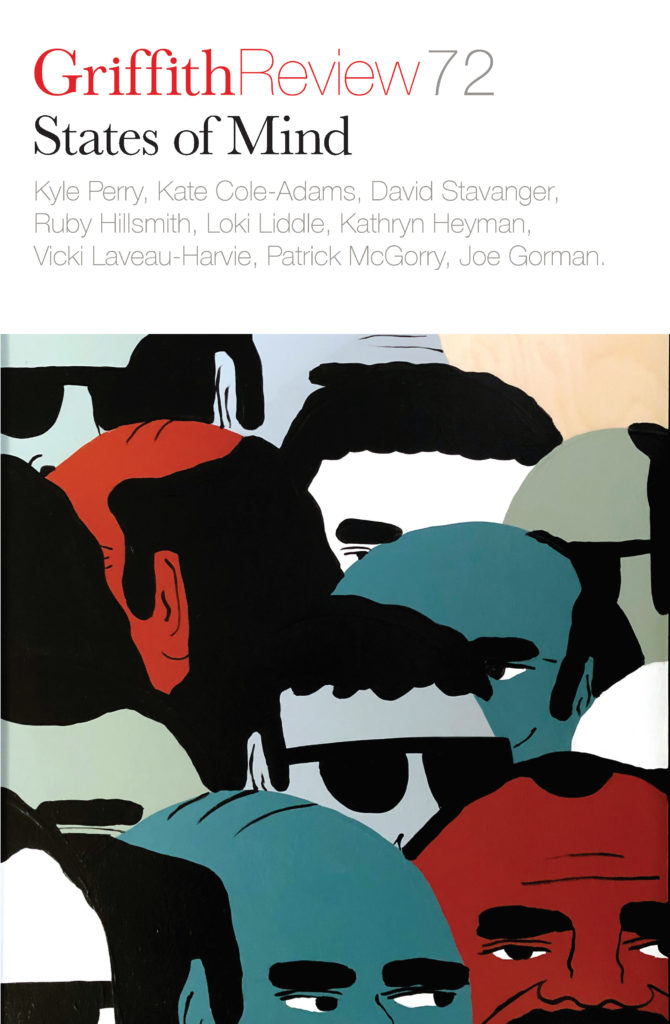

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-59-7

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

The ship, the students, the chief and the children

Non-fictionThe power of the fossil-fuel order depends on foreclosing any kind of political and institutional decisions that would see societies break free from the malignant clamp of coal, oil and gas corporations. This power also depends on eliding alternative ways of seeing. In one sense, the whole of the political struggle against climate change can be understood as an effort to make corporate and political decision-makers see, such that they are required to act.

More from this edition

Pandography

Picture Gallery Graph, noun, a diagram representing a system or network of connections, values or interrelations among two or more things. -graph, suffix, combined with nouns to...

Coal and meter

PoetryThe poet digs down a decade with her plastic pen, rests by the ancient seam, Earth’s little little black dress boudoir-veined. Poet and coal are looking for love, unelectric...

Embracing ugly feelings

MemoirTHE FIRST TIME I was hospitalised, my mother visited me in the dank psychiatric ward bearing a three-tiered lacquer bento box packed with handmade...