Featured in

- Published 20221101

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-74-0

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

The town turns over: Audio edition

MediaListen to author Laura Elvery read aloud her short story 'The town turns over', a poignant exploration of ageing, memory and endings. This story appears...

More from this edition

The supper

Poetrywhere Sacrificer and Sacrificee, still fragrant with the Blood of Morning and Harvest, gather by twisted Beak and crooked Hand

Tastemakers

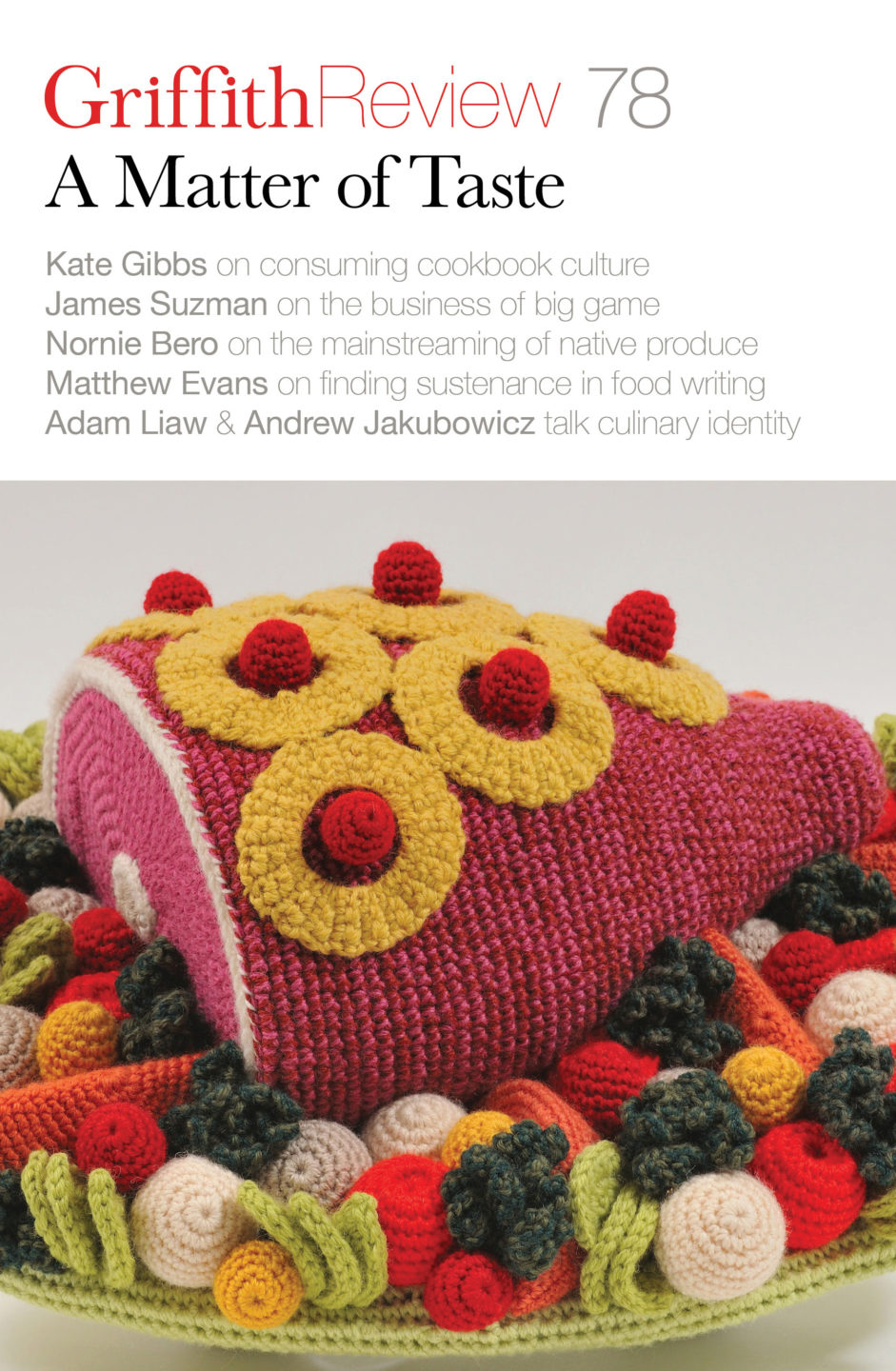

IntroductionI’m still pleasantly mystified by our obsession with food – our need to talk about it, remember it, photograph it and analyse it, to eat our feelings and compare our lives to buffets and boxes of chocolates.

Eat me in the city

MemoirThe idea of having my body lovingly prepared and cooked as a feast for friends seems like a particularly beautiful death to me, and one that needs careful planning and consideration.