Featured in

- Published 20220428

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-71-9

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Click here to listen to Editor Ashley Hay read her introduction ‘Beyond the frontier’.

A LONG TIME ago, I spent a day on a replica of HMS Endeavour on Sydney Harbour. It was an uncanny experience. This ship, a reconstruction, seemed an almost inconceivably small thing to have delivered so much change and disruption to the Southern Hemisphere. The knowledge that I was part of the settlement that had resulted – over time – from its visit had to sit alongside the havoc that settlement had brought. At a level of simple geography, it was also uncanny: Sydney Harbour is a body of water the original ship never entered, embraced by shorelines its sailors never saw. This voyage wasn’t re-creating anything that had ever actually happened.

I carry two sensations from that day, more than fifteen years ago now. The first is the smallness of the ship’s two finest cabins assigned to Lieutenant James Cook, its captain, and Joseph Banks, the rich young man who craved – and got – a ‘grand tour’ that would circumnavigate the globe. Each had just 2.4 square metres of floor space, with ceilings 1.7 metres high. Both men, over 1.8 metres tall (or six foot in their measure), must have had to dip their heads and duck. The second is the skewed view through the windows, their uneven glass rippling the scenes outside into distorted versions of themselves. Changing the world waterborne visitors saw through a thick and alien lens.

If there’s nothing new in saying that Endeavour and its narrative was only ever one small part of the unfolding story of this continent, its primacy – after more than a quarter of a millennia – is still surprising. It was 250 years after the Endeavour’s crew made landfall in the place they called Botany Bay before the message called out from the shore by the Dharawal residents of Gamay was correctly translated. Not ‘go away’, as Cook presumed and recorded, but ‘you’re all dead’. ‘When our old people saw the Endeavour coming through, they actually thought it was a low-lying cloud because all they could see was whiteness,’ Ray Ingrey, the deputy Chair of the La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council, told the ABC on 29 April 2020, the sestercentennial anniversary of Cook’s landing. ‘In Dharawal culture, that low-lying cloud means the spirits of the dead have returned to their Country and so they saw almost ghosts. So when the two men opposed the landing, they were protecting the Country in a spiritual way from ghosts.’ As Dharawal Elders collaborated with museums, libraries and other archival repositories to re-evaluate European records, Ingrey was hopeful it would be possible to ‘give the broader Australian public a more authentic story and a story that makes sense’.

A MORE AUTHENTIC story, and a story that makes sense. There’s more to any reckoning than stories – there’s the urgent need for systemic change that undoes gaps, discrimination and statistics; for an end to structural violence and inequity; for voice, treaty, truth in this instance and in that order. But stories stand as part of that whole and a necessary way towards it.

Griffith Review’s engagement with ideas of reckoning stems partly from its commitment – across its nineteen years of publication – to Australia’s First Nations voices and perspectives in its editions. It stems partly from First Things First, the landmark volume co-edited by Sandra Phillips and Julianne Schultz in 2018, which itself had to pivot to acknowledge the Turnbull government’s left-field response to – and rejection of – the offer of the Uluru Statement from the Heart the previous October. It stems partly, too, from the publication of the first major essay by lawyer and activist Teela Reid on 26 January 2020 calling for that year to be one of reckoning, not reconciliation; calling for all Australians to show up for the critical work of re-evaluation, reparation, recognition and so many other things beyond the idea of reconciliation.

Teela Reid is an integral part of this edition, bringing to its mix not only her commitment to the centrality of reckoning in the Australian project across recent years but also, as a contributing editor, the curation of key commissions from Jasmin McGaughey, Merinda Dutton, Megan Davis, Thomas Mayor, and Kirli Saunders in conversation with Lilly Brown and Genevieve Grieves. She has also written a powerful new essay on matriarchy, truth-telling and love – and if love sounds like an incongruous word, think of the definition proposed by powerhouse thinker and social activist the late bell hooks. To her love is a verb, a doing rather than feeling. It’s a repudiation of all kinds of domination, a ‘combination of care, commitment, knowledge, responsibility, respect and trust’.

To approach stories, let alone people, with that combination is to allow them to exist in their most nuanced forms. It’s to allow for new possibilities to emerge; to allow for development, adaptation, revelation and – above all – change.

Griffith Review’s engagement with ideas of reckoning also springs from ongoing engagement with the man who gave this journal – as well as its host institution and other institutions and locations across this country – its name, and we’re grateful for the support of Griffith University’s Arts, Education and Law Group as our publishing partner for this particular edition.

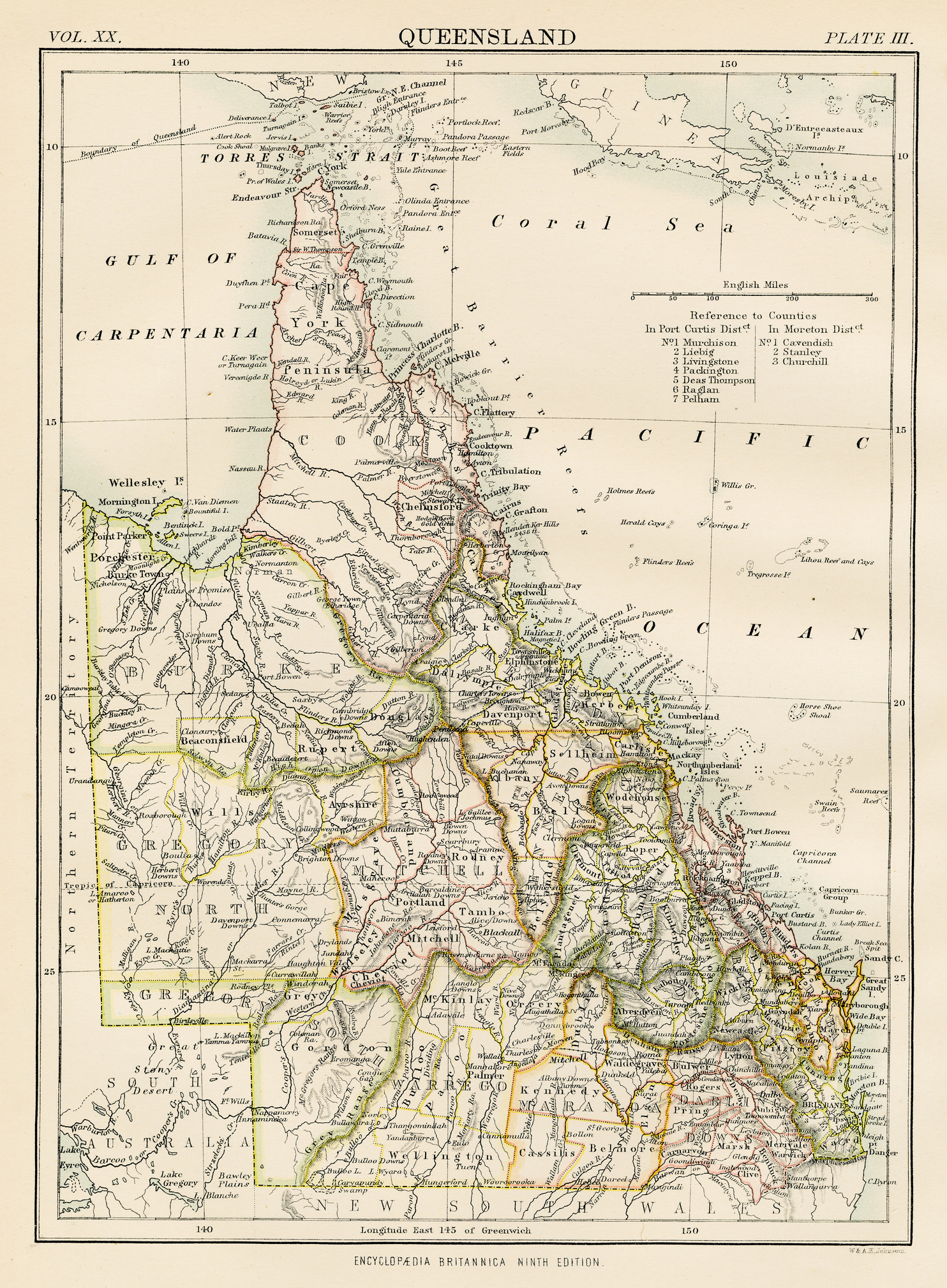

Sir Samuel Griffith’s life produced outcomes that not only impacted people in his own time but still impact people’s lives now – from the continuing citation of judgements he made, particularly as the first Chief Justice of the new Federation of Australia, and through the broader global implications of adaptation of his Queensland Criminal Code by other states in Australia and beyond in places including the Mandated Territory of New Guinea, Palestine (and, subsequently, Israel) and several African countries, among them Nigeria.

In 2021, historian Henry Reynolds published Truth-telling: History, Sovereignty and the Uluru Statement – an exposé of Australia’s colonial history as ‘conduct that wilfully ignored imperial direction from Britain and even the law itself’, as one reviewer described it. Several sections spotlit Griffith – alongside other fathers of federation, such as Sir John Forrest and Sir John Downer, and key colonial figures, including James Cook and Lachlan Macquarie. Looking particularly at the violent settlement of Queensland in the latter part of the nineteenth century, when Griffith was twice premier of the colony, and then its Chief Justice, Reynolds writes,

Like his colonial contemporaries…Griffith knew exactly what was happening out there in the vast hinterland. He did little to stop the killing. How then should history remember him? Will his high reputation survive the rigours of truth-telling? Perhaps more to the point, should it survive?

These are important questions for Griffith Review to take up: Griffith’s life, like those of many historical figures, is known by a kind of shorthand, a sketch of particular moments, decisions and deeds. He was one of many colonial leaders whose lives and actions merit not just revisiting but also new scholarship, new questioners at work in the archives. In The Idea of Australia (2022), Griffith Review’s founding editor, Julianne Schultz, notes the decision to use his name in the context of this journal. There were, she writes,

few biographies of the man to flesh out his story, and his name had been appropriated by groups associated with libertarian think tanks. [In 2003], we settled on describing him as ‘iconoclastic and non-partisan’. Over time, we learned that his legacy was more complicated. This did not really capture the fraught complexity of his contribution in a brutal colony.

At the moment, our biographical note mentions Griffith’s opposition to ‘blackbirding’, but not his involvement in the mass expulsion of three quarters of the Pacific Islanders working in Australia in the first years of the twentieth century. It highlights his involvement in the long process of drafting Australia’s Constitution, but not his clarity that that document must remain a nimble and malleable thing.

There is still much to uncover of this ‘fraught complexity’ – not only from Griffith’s life but from many others of his place and time.

In new work for this edition, Henry Reynolds returns to Queensland to explore what made settlement of this landscape, this frontier – and the violence that accompanied it – different to the annexation of other parts of Australia. Beyond the intellectual architecture used to contextualise the decisions of the late eighteenth, nineteenth, early twentieth centuries – including the Doctrine of Discovery, terra nullius, the White Australia policy, among so many more – conscious and intentional decisions were being made throughout this time about the treatment and persecution of other human beings. The first national attempt to locate the sites of conflict that rapidly accreted across Australia as one population sought to supplant the already resident one was released by the Colonial Frontier Massacres Digital Map Project at the University of Newcastle five years ago in 2017. Its fourth instalment, released in March 2022, identified 416 sites – an ‘indicative rather than definitive’ figure. Lay that nationwide number against work done by social historian Raymond Evans and Robert Ørsted-Jensen to estimate that upwards of 65,000 lives were lost in Queensland alone during the frontier wars. That’s more than the total number of Australians who lost their lives in World War I – and that’s in just one state.

People knew this was happening – ‘the realities of frontier conflict were well-known,’ Reynolds writes in Truth-telling. ‘No Queenslander with any interest in public affairs could be unaware of the way things were.’ Some protested; others supported. But the impacts of these actions and decisions are still felt. As Megan Davis – lawyer, activist and Pro-Vice Chancellor Indigenous at UNSW – writes in this edition, one clear necessity is for Australia to dispense with ‘the popular but false notion that Australians do not know who we are. It is not true that “we weren’t told”.’

Perhaps the idea of everywhen is useful for all Australians here. This is a term coined by the anthropologist WEH Stanner to explain to non-Indigenous readers that what they heard of as ‘The Dreaming’ was not a thing of some distant past. ‘One cannot fix “The Dreaming” in time,’ Stanner wrote. ‘It was, and is, everywhen.’ Perhaps everywhen is a way of understanding that what happened in 1788, 1838, 1868, 1906, 1967, or what will happen in 2022, 2050, 2088 or any time beyond, leads to and comes out of the moment we’re in now.

This is a space that David Denborough has thought into for more than two decades. Denborough, a narrative therapist, is descended from both Sir Samuel Griffith and from early frontier settlers in Queensland’s north-west. To him, the idea of everywhen enables a more direct conversation with his forbears – about their world and his and the lines that run between the two. His new letter to his great-great-grandfather for this edition lays out a model of communication between that then, this now, and a different kind of future. It’s an intimate and powerful intervention in what novelist Alexis Wright has called ‘the storytelling wars’.

THIS BOOK SPOTLIGHTS some of the work of reckoning and recalibration that’s already taken place or underway and what might happen next. It maps small and generous acts of accommodation – like Tony Birch’s last trip with his father – and shines new light on often-told stories. It charts the ebb and flow of change and adaptation that’s never been a more crucial part of the human experience than it is today. It explores how ideas of power, democracy, imagination, conflict and exploitation are transported around the world – willingly and under duress, just like people. How stereotypes and artefacts from the Atlantic – from Haiti, from the slave trade – are developed and despatched; how some of them fetched up here. How the idea of a European gothic manifested in this place and was adapted by new First Nations voices. How the reckonings of other countries, other conflicts arrive here – from Sri Lanka, from Lebanon – to be impacted by new homes and relationships in this place.

How the work of re-storying goes on.

Historian Shino Konishi describes re-storying as central to the project she leads under the auspices of the Australian Dictionary of Biography. The ADB’s first volume, published in 1966 and covering the years 1788 to 1850, featured only nine profiles of Aboriginal individuals out of its original 1,182 entries – ‘even though Aboriginal people represented the majority of the population in Australia until at least the mid-1840s’, as Konishi has noted. Not only does this new project – ‘An Indigenous Australian Dictionary of Biography’ – underscore its own position as partial rather than definitive, it also disrupts the idea of the time spanned by that label ‘Australian lives’ with biographies of Mungo Lady and Mungo Man, who lived around 42,000 years ago. It also highlights ‘the diversity of Indigenous people’s historical experiences’ and provides narratives that Konishi describes as helping ‘to better understand our histories, our ancestors, our cultures, and our lifeways’. If the biographies in the ADB’s earlier volumes were of people already well known, people who had impacted ‘on colonial/mainstream Australian society’, this decolonised dictionary scoops in ancestral figures, rainmakers and song men and women, painters and healers and so many more. In this way it brings ‘to light stories of Aboriginal men and women who maintained traditional practices, and were renowned within their local communities for their knowledge and skills’.

These are crucial contributions to making Australia’s story whole.

COME BACK TO Queensland. Come to the lands of colonial Brisbane when the number of Goorie residents and new settlers was in balance, as if the story could have then gone either way. This is where Melissa Lucashenko sets her new novel Edenglassie, an extract of which is published here for the first time. Come to Mithaka Country, Channel Country, to discover a peace agreement more than 130 years old. Come beyond Cape York to Zenadth Kes, to one island frontline of a changing climate and a complaint made to the United Nations about the Australian Government’s inaction on climate change. A vast reckoning to be made there as well.

And now, come further back, to James Cook himself, a man to whom the story of Australia’s colonisation will always return. Sailing north from Botany Bay, the Endeavour made fourteen further landfalls along the coast of today’s Queensland before sailing to Thunada, which Cook named Possession Island. In this place, on 22 August 1770, Cook described himself as artists later depicted him:

I now once more hoisted English Coulers and in the Name of His Majesty King George the Third took possession of the whole Eastern Coast…by the name New South Wales, together with all the Bays, Harbours, Rivers and Islands situate upon the said coast.

There is another version of this story – a version that exists beyond Cook’s journal, beyond any of the other British records, beyond the imaginations of any artist or the British Admiralty – and Thomas Mayor tells it here.

Come back to the beginning; start again.

THAT SHIP-RIGGED, FLAT-BOTTOMED, three-masted barque, Endeavour, had a top speed of seven to eight knots, or around fifteen kilometres per hour. But even moving at only two or three times’ walking pace, it would still push out a wave in its wake. That water turned and moved along the eastern edge of this continent; perhaps it’s still in play in some part of the world’s ocean even now. Its ebb, its flow.

What is the truth of a moment? And how can the world approach any act of truth-telling in this particular age of power and noise, disconnection and division; of climate, cancellation and constant outrage? What can any act of truth-telling look like in what we call – or are starting, dismally, to recognise and understand as – a post-truth world? How can truth-telling work in spaces where facts seem to matter less and less?

This is not a pitch for relativism or the complete subjectivity of any narrative or moment. But perhaps it is a pitch for the imperative of taking up – or seeking out – the invitation to put yourself in another place, another story. Putting yourself in a small ship, rebuilt, and imagining some of what it might have been to be there and some of what came from its travels, everything that set in train. Putting yourself on the shores of that country, watching those ghosts arrive. Putting yourself on the shores of your own country, your own ancestors, wherever that is, and in the everywhen.

I am writing these words on the lands of the Jagera people, the rich and fertile space along the banks of Maiwar, south of its now citified reach at Kurilpa. I am writing this beyond the end of one late and suddenly flooded summer, ahead of an electoral season already shaping up to be brutal – with loud statements that sound more focused on clutching onto power than on any policy or vision. In this place, with the unique invitation of its long, long history and the presence of the world’s longest continuing culture, does this mark out who we want to be? The Uluru Statement from the Heart was not presented to Australia’s government; it was presented to the people, because – as Bridget Cama says in conversation with Patrick Dodson for this edition,

we have had those generous acts in the past, such as the [Yirrkala] bark petitions, presented to parliament – and they end up on the walls. If that’s not the most disrespectful thing that can happen, I don’t know what is.

It takes energy to live with mobility, to be willing to shift and to change. To be willing to disrupt ourselves. Patrick Dodson sees

…many opportunities for us as Australians. But it does require generosity of spirit and an openness of heart and a preparedness to go into those realms of the darkness with confidence that we’re capable of coming out the other side and seeing the sunlight. We’re not all going to be trapped into some dark vortex that takes us nowhere.

THE ORIGINAL ENDEAVOUR was built from white oak, elm, pine and fir – northern trees that bore that hemisphere and its assumptions this far south. It was scuttled in 1778 in a blockade off Rhode Island, part of the American Revolutionary War.

Two replicas exist, like the possibility of at least two other tellings of its story. One has journeyed all over the world; this is the one that sails sometimes on Sydney Harbour. The other stayed in northern England, not even designed to go to sea. It changed hands from one private owner to another for £110,000 in 2017 – such a discrete narrative arc compared with the vast reach and impact of its famous forbear.

How do these two ships work as memorials for a land with so few monuments to the history that followed in the wake of the original? This is a country where the dearth of ‘public monuments of significant Aboriginal leaders or of historical events such as massacres and frontier battles’ was lamented in the opening session of each and every dialogue that led to the Uluru Statement from the Heart, as Megan Davis notes. And those absences compound the potency of names that are deployed to memorialise lives and actions in this place. But, as Henry Reynolds wrote of Sir Samuel Griffith in Truth-telling,

A commitment to truth should strengthen our determination to follow where the evidence leads us, even if we need to engage in the iconoclasm that was, after all, nominated as a chosen path in the mission statement of Griffith Review.

That mobile new Endeavour is made partly from Australian wood – karri for the tiller, jarrah for the frame and the hull planking, Western Australian she-oak for the blocks. I love the sense of this continent, of some of what’s unique about it, being in its hull, its beams. As if we can all make a new ship, a different ship, even for a ship as potent and powerful as this, if we make it from the unique things of this place.

17 March 2022

Share article

More from author

Between different worlds

IntroductionAntarctica offers windows into many different worlds...

More from this edition

‘The True Hero Stuff’

GR OnlineI grew up in a Queensland still so saturated with racist ideology that my own identity was hidden from me until as a teenager I started bringing home questions about our family’s tan skin and curly dark hair. Forty years later I was very well aware that non-First Nations writers usually mine a vast well of ignorance and stereotype when they attempt to bring Aboriginal characters or themes into their work.

Mud reckoning

FictionTHERE IS NO such thing as bad Country; there just happens to be bad custodians.

An archive for the dispossessed

EssayAs an archive, the Jaffna Public Library told a story about the place of the Tamil people in Sri Lanka. The political authorities of the 1980s wanted to suppress that narrative – and burning the archive was a quick and conclusive way to do it.