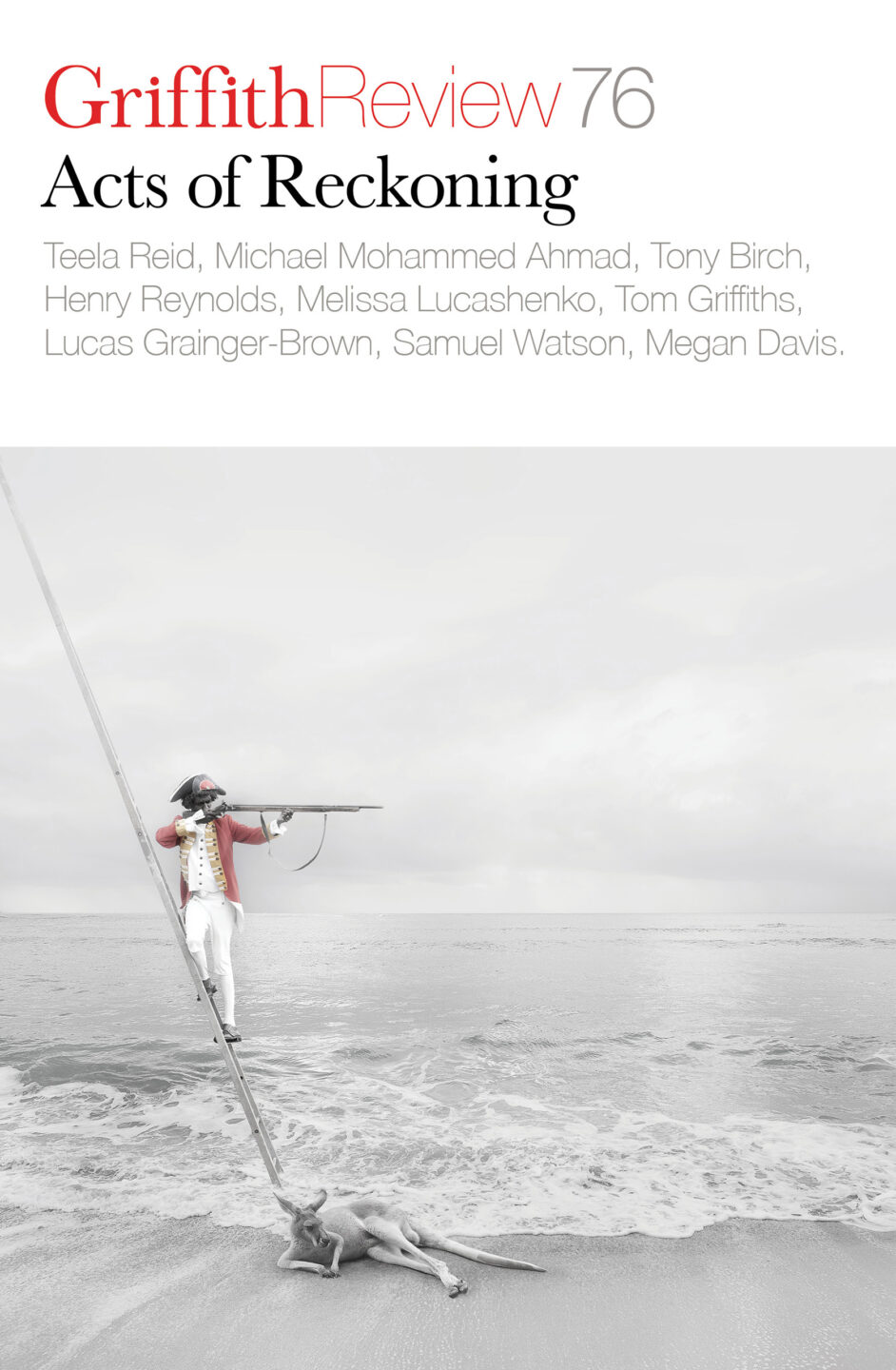

Featured in

- Published 20220428

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-71-9

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

‘Arriving at the entrance to the yard, I met a white object, which proved to be a Kanaka in his Sunday clothes.’

Carl Lumholtz, Among Cannibals: An Account of Four Years’ Travel in Australia and Camp Life with the Aborigines of Queensland, 1889

FROM THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY novels of Rosa Praed well into the twentieth century and beyond, Aboriginal people have been scrutinised and written about by outsiders in terms both simplistic and racist. Such fiction, especially in the era when the novel was about as powerful as Netflix is today, initially served an economic and social as well as a literary purpose.

Stories by authors like Rosa Praed and Brian Penton acted as propaganda, and either justified – or at best simply refracted – racist attitudes about the taking of Aboriginal land and the stealing of Aboriginal lives, labour and freedom.

I expected to find as much when I began researching my new novel, Edenglassie, in 2019. I grew up in a Queensland still so saturated with racist ideology that my own identity was hidden from me until as a teenager I started bringing home questions about our family’s tan skin and curly dark hair. Forty years later I was very well aware that non-First Nations writers usually mine a vast well of ignorance and stereotype when they attempt to bring Aboriginal characters or themes into their work.

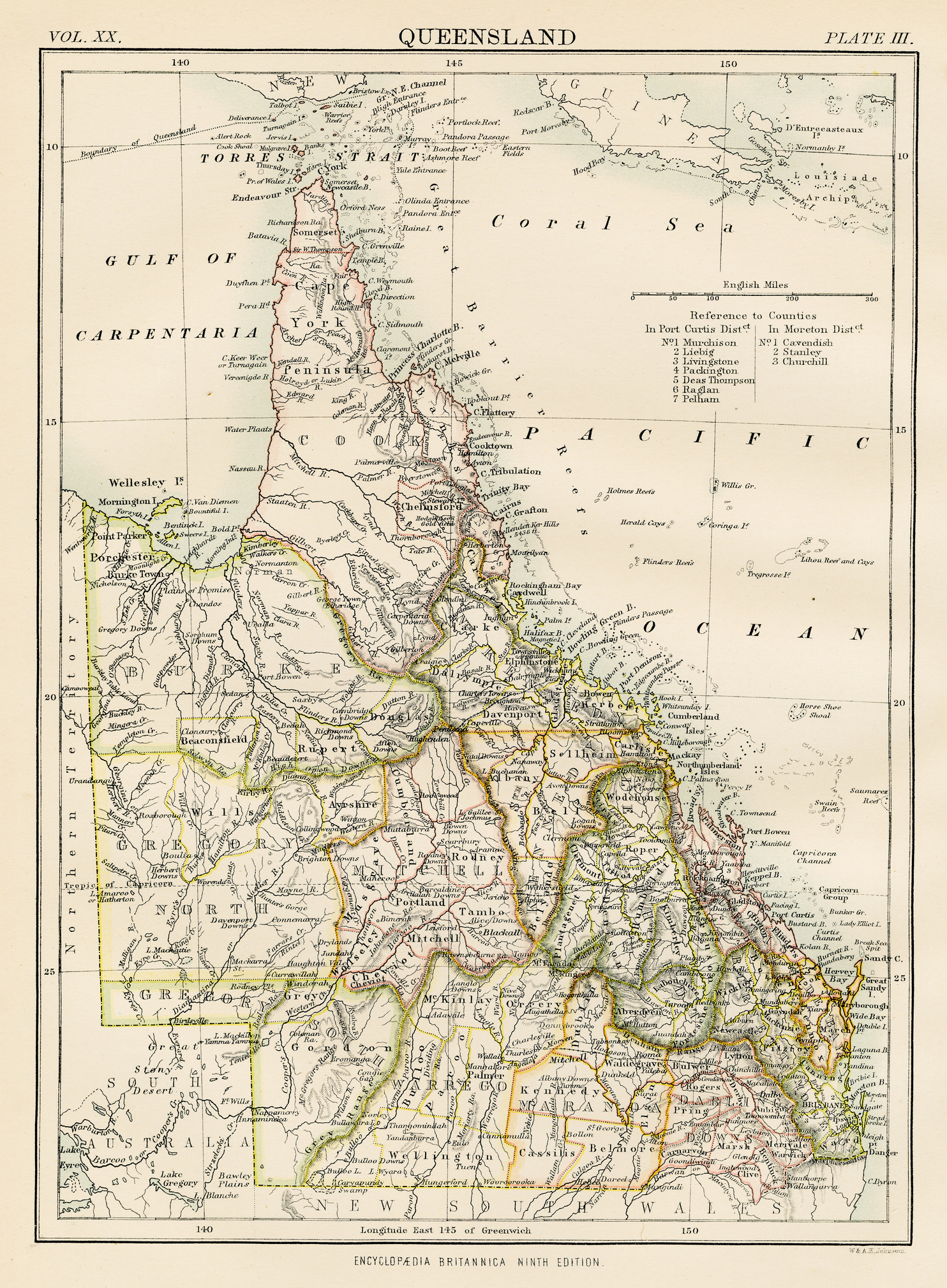

So I was unsurprised to find a dizzying edifice of white supremacy at the heart of Queensland colonial literature. I had already browsed the 1875 Parliamentary Papers in the Fryer Library and knew from those sources that invaders in the north of the state considered it a ‘kindness’ on the northern frontier to slaughter Aboriginal children. The orphaned Black kids would otherwise starve to death in the aftermath of the mass murder of their clans; in 1875, putting them ‘out of their misery’ was viewed in some circles as a ‘humanitarian’ act. I already knew, too, about the naming of places like Gin’s Leap and Skull Creek, though I had yet, in 2019, to discover an obscure reference to a ‘field of skeletons’ at Ipswich – a field that, as far as I know, goes unremarked and unmemorialised in our literature today.

The early Queensland poet Eva O’Doherty (1830–1910) is one early exemplar of this racial supremacy. In ‘Queensland’ (1862), the only poem in her two published volumes to deal directly with life in this hemisphere, she writes of an imagined Queensland ‘without legends’. With unconscious irony, she describes a place unawakened because it is unsung:

No poet-fancies o’er thy skies

Spread tints that hallow, live for ever;

No old tradition’s magic lies

On mountain, vale, and river.

There is no heart within thy breast,

No classic charms of memories hoary,

No footprint hath old Time imprest

On thee of time or story…

Oh, whose shall be the potent hand

To give that touch informing,

And make thee rise, O Southern Land,

To life and poesy warming?

O’Doherty appears to have been supremely ignorant of the ‘magic’ that already lay thick on each ‘mountain, vale, and river’ she encountered. On the evidence here, she either had no contact with Aboriginal people, who could have easily disabused her of the racist notions underpinning her verse, or alternatively had met them and went away unenlightened. (A scenario, incidentally, that’s played out exhaustively in Australian writing circles to the present day.) It’s often difficult for us to convince Australian authors that we have any superior insight into our own culture and lives. Settler Australians have read Tiddalik the Frog in kindergarten, after all, or watched David Gulpilil hang himself on a mango tree in Walkabout. What could they possibly have to learn from us?

I went on to read Rosa Campbell Praed, the first major novelist of Queensland. Praed (1851–1935) wrote mainly commercial romances for an English market, romances that drew directly upon a childhood lived fairly close to the colonial frontier. Her writing placed white damsels in what she saw as the harsh and often ‘uncivilised’ frontier lands of what was then still northern New South Wales. She asked implicitly and explicitly how are ‘we’ – by which she meant British settler Australians – to live here in this hard and ‘distant’ place? Her Queensland portrayed in Lady Bridget in the Never-Never Land (1915) was a place of intermittent war with the First Nations and of regular drought as well as terrible isolation and cruelty. She sought over and over to answer one question: what did Daddy do in the war, and how was she, Rosa, meant to live with it?

Unlike the majority of settler writers who followed, Rosa had had intimate relationships with Aboriginal people. Growing up very near the frontier, she knew Yugambeh people, first at Bromelton near current-day Beaudesert, and later other First Nations in the Burnett, several hundred kilometres north. In both settings she befriended some colonised Aboriginal people – especially one youth, Ringo – just as she shunned others. Like many colonial whites, Praed gleaned a certain amount of cultural knowledge, and this often found its way into her writing, though her ‘recollections’ must be taken with a large grain of salt.

Rosa’s father, Thomas Lodge Murray-Prior, was an active and eager participant in frontier massacres. He shot Aboriginal people as part of the revenge expeditions that followed the 1857 Hornet Bank attack in Central Queensland, two days ride from his Burnett property. In My Australian Girlhood (1902), Praed refers to her mother building a fire to signal to workmen that all was well at the homestead when her father ‘…was out with the squatters taking vengeance on the blacks after the Fraser murder’.

Not much room for equivocation there. And there is a chilling photo of a ‘stockman’s hut’ in My Australian Girlhood, too, showing the interior of a basic bush dwelling with seven rifles racked on the wall, within easy reach of the workman’s single bed. It’s impossible for an Aboriginal reader to look at these pages of Praed without wondering just who those rifles were used on.

In My Australian Girlhood, Praed describes pioneering whites like her father as

A brave, reckless band. Quick to love and quick to hate, full of pluck and endurance, dauntless before danger…very few of them did jib at the job, and some showed the true hero stuff…

Later, in Lady Bridget in the Never-Never Land, Praed wrote explicitly about frontier genocide, probably basing her love interest on the real-life frontiersman Wills, the child survivor of an Aboriginal sortie. Her pastoralist hero, Colin McKeith, is painted as problematic and brutal, but also very much ‘heroic’ as he murders Black landowners in the forging of a ‘pioneer’ existence in Queensland.

Lady Bridget in the Never-Never Land does raise interesting and compelling arguments against colonial murder and about colonial race relations. Its heroine, Lady Bridget, describes the murder of Aboriginal people as just that, but ends by forgiving her estranged and warlike husband for his evil crimes. Her conclusions are cast, ultimately, in the typical outlook of her times. The novel ends effectively as an apologia for the criminality of her ‘brave, reckless band’ of marauders.

As a girl, Praed had wanted to marry the ‘tame’ Aboriginal boy Ringo; but at the same time, her father openly murdered First Nations people and was socially sanctioned in doing so. She wrote that the Blacks were widely ‘destroyed like vermin’ but also claimed that the posse her father rode in to avenge Hornet Bank ‘held firm to the traditions of English warfare’.

She reported that men of her father’s social cohort, and very likely her father as well, hushed up horrors other than murder. These were presumably either infanticide, rape, child rape or a mixture of the three. She writes as though it is sensitivity and tact she is describing and not a criminal conspiracy:

There are other incidents of that raid spoken of in whispers and at such times the men in the verandah fall silent and look very grave. They shake the ashes from their pipes and cut up more tobacco.

Praed – who knew many Aboriginal people across different clans – was able to describe Moreton Bay in 1841 as ‘scarcely settled’. She wrote as though the several thousand Murri and Goorie people alive at the time – and still outnumbering the white colonists – were so many kangaroos or eucalyptus trees. With her work described by British academic Len Platt as ‘toe-curlingly paternalistic and condescending’, it says something that Praed is today often seen as the best intentioned of a bad bunch when it comes to colonial writers of Aboriginal characters.

AFTER DIGESTING PRAED, I turned to Brian Penton’s Landtakers, a novel subtitled ‘The story of an epoch’ and one imagined by its author as a successor to Henry Handel Richardson’s The Fortunes of Richard Mahony. Penton (1904–51) was very much a part of the intellectual class of his time, the 1930s and ’40s. He was a newspaper editor of note, a leading journalist and friend of Billy Hughes; a man who thought of himself as a ‘classical liberal’. He published Landtakers in 1935 and had at least one elderly white informant who had been alive on the Queensland frontier. In a sweeping narrative about the ‘divided colonial psyche’, Aboriginal people are written as dangerous, or primitive, or both. Free Aboriginal people were always in the way of progress and as a result had to be dead or dying on the page, since the magnificent British civilising project had arrived to take our place as the Lords of the Antipodean Manor.

In a typical scene in Landtakers, Penton’s English protagonist, Cabell, has not long distributed tobacco to the local Aboriginal landowners in a place where he’s rocked up uninvited with his thousands of sheep:

Two days later the tribe came down and pitched their gunyahs on the bank of the river…the horses were restless all night… Even the stupid sheep hated the smell of the blacks…their eyes were purple rimmed and the palms of their hands grey. They had wide mouths, low foreheads, and noses that lay flat on their faces, with big nostrils turned up and out. They were not like men somehow – subhuman.

In the next chapter, when Cabell has established his ‘selection’, Penton writes:

Things went from bad to worse. One day he caught a black sneaking away with a leg of mutton from the gallows where the carcass…killed for rations was hung every Saturday night. He snatched up a stockwhip and chased the black into the corner of the yard with it. The thief was the ugly one-eyed devil, and twice already he had cut across Cabell’s temper by coming into the yard and looking at the storeroom. Now he raised a howl that brought up half a dozen hulking brutes, armed to the teeth. After a lot of arguing and gesticulating, they were got off the premises.

Cabell was for riding out at once to drive the lot of them from the valley at the point of a gun but Gursey held him back… But the trouble was started. It came to a head that very night, and by morning not a black was left in the valley.

It’s not made entirely clear to the reader what happened ‘that very night’, but the white stockmen are described as ‘nervous’ afterwards, and three Black men are definitely shot dead within twenty-four hours by Dan the crazed shepherd. Dan was ‘provoked’ to murder by the noise of a corroboree, after which murders: ‘“Dang him!” Tom swore. “Always said that man ’ad no tact!”’

Rosa Campbell Praed’s dozens of commercial novels spanned four decades beginning in 1880. Penton came a generation later, with Landtakers in 1935. In 1959, the leading academic and UQ English lecturer Dr Cecil Hadgraft published a text called Queensland and Its Writers: 100 years, 100 authors.

Hadgraft analyses another very early Queensland novel – Adventures in Queensland by FA Blackman – and describes it this way:

…there is probably no other Queensland novel so full of useful information as Adventures in Queensland (1879)… This begins as history and develops as a guidebook to adventure or a manual for newcomers. The area is west of Maryborough, the period the late forties and the fifties… The greatest interest, apart from details, lies in Blackman’s attitudes. He is a spokesman for the squatters, whom he portrays as benefactors of the State, unappreciated and badly treated by the various Land Laws. Anything that stands in the way of these gentry is consequently bad, for example, aborigines [sic]. Blackman makes a few concessions and does recognise that some whites were sometimes to blame; but in general he treats a ‘dispersal’ of aborigines as a sort of slightly risky sporting venture rather like big game shooting. The account reads sometimes a little callous: ‘Three of them were imprudent enough to climb up trees, whence they were picked off like squirrels, falling with a dull thud.’

Such parts may seem heartless, Hadgraft writes, but they also seem actual. It is likely enough, Dr Hadgraft adds in 1959 – and I quote – ‘that after a few such expeditions the taste would grow on one’.

Hadgraft in the foreword to this textbook also mentions in glowing terms the poetry of James Brunton Stephens. He specifically refers to the poems ‘My Chinee cook’ and ‘A piccaninny’ as ‘deft’ and ‘uproarious’.

‘A piccaninny’ has the nineteenth-century poet, Stephens, spying and addressing a naked Aboriginal three-year-old, whom he describes as a ‘smockless Venus’ and a ‘Helen in the nigger apprehension’. Her childish beauty and innocence trouble the poet, as she has

No faint forehearing of the waddies banging

Of club and heelaman together banging

War shouts, and universal boomeranging

[…]

Die young! For mercy’s sake, if thou grow older

Though shalt grow lean at calf and sharp at shoulder

And daily greedier and daily bolder,

A pipe between thy savage grinders thrusting

For rum and everlasting baccy lusting

And altogether filthy and disgusting…

[Later: ‘Oh, die, of something fatal, I beseech thee!’]

Just such another as the dam that bore thee

That haggard Sycorax now bending oe’r thee

Die young, my sable Pippin, I implore thee!

This genocide apologist, Stephens, is described in Hadgraft’s 1959 text, published by the University of Queensland Press, as ‘not our greatest, but our most cultivated poet’. According to his foreword, Hadgraft’s own book was endorsed by UQ’s Vice-Chancellor and by the University Senate.

Probably I need to mention here Patrick White’s A Fringe of Leaves, published in 1976, three years after his Nobel Prize, in which White uses Aboriginal society as a literary device to plunge his class-jumping Cornish peasant girl into absolute ‘primitive savagery’ on Butchulla Country a little north of Brisbane.

The Butchulla women of Fraser Island were not women in A Fringe of Leaves but rather ‘hags’ and instead of speaking their own languages, as intelligent and insightful women generally tend to do, they are left to communicate in what White describes as

curious noise…animal gibbering…horrid shrieks…howls…excited jabber…[and] hissing and chattering.

I could go on, but I won’t.

THESE EXAMPLES – A few fairly random selections from a vast panoply of racist portrayals – should give some idea why I embarked on writing a novel of colonial South-East Queensland.

I started researching Edenglassie full time in 2019 with the basic idea that I’d undo some of the racist mythmaking that had painted us as simpletons and nomads, wandering aimlessly from campsite to campsite, enjoying a ‘natural’ life – without philosophy, government or ethics – until the arrival of the British plunged us into chaos and then quickly into extinction. I perhaps had in mind a literary version of The Other Side of the Frontier.

One great difficulty in writing Edenglassie has been how to subvert the trope of the dying race. As I’ve learnt in a quarter century of writing, two concepts are very hard to dislodge from the mind of the average Australian reader. The first is the idea of Aborigines as the Dying Race; the second is the Pitiful Aborigine Who Has Lost Her Culture. They are two sides of the one debased coin.

Both tropes were central to early colonial literature and they were central because they are superbly convenient to the colonising process. A dead Aborigine can’t claim land rights or protest about massacres or achieve any semblance of justice. And a so-called ‘deculturated’ Aborigine can be laughed out of court, as the Yorta found to their cost in 1999, when a white Australian judge told them that their identity and thus their native title had been ‘washed away by the tide of history’.

Normally I counter the Dying Race trope in my books by only writing about life, about living Blackfellas. This has been a firm rule of mine since I began publishing fiction in 1996 – no killing off Aboriginal characters. We need to be alive on the page if Australia is ever going to imagine us living good lives. In a quarter century there has been a big enough shift in the Aboriginal stories on Australian pages, screens and everywhere else that I do now feel able to occasionally have a character pass away, as with the ageing grandfather in Too Much Lip.

A colonial novel, though, has to acknowledge that mass bloodshed happened – here, in South-East Queensland – and that war was waged even though it was never officially declared. In 2014, the Brisbane historian Robert Ørsted-Jensen estimated that several thousand more Aboriginal people died on the Queensland frontier than Australians in World War I. In 2021, researchers Lynley A Wallis, Heather Burke and Mia Dardengo put the estimate even higher, at over 100,000 Aboriginal deaths on the Queensland frontier.

Lest we forget.

More than one massacre occurred within two kilometres of the Brisbane CBD, and some of these form part of my novel-in-progress, Edenglassie. So the question of how to show colonial brutality without leaving First Nations characters only as dying victims in the mind of the non-First Nations reader – or indeed lacerating my readers so much that they can’t continue – has been a vexed one. I think I’ve solved that quandary, but only time and publication will tell.

Edenglassie as a modern First Nations novel has to do many things. It intends to portray the governance, stability and sophistication of sovereign Aboriginal nations, not shown at the point of first contact but viewed from the point of early colonisation. It must give humanity and beauty to Aboriginal characters, all of whom deserve a character arc. It needs fully rounded European characters, too, with different class and cultural and psychological qualities. It has to show the cruel injustice of the British invasion without completely repelling readers or causing me to lose the will to live in the writing of it. And it has to be a love story, because we are human beings who love, and because Blackfellas deserve joy and romance on the page, too.

I took three years meticulously researching the history of colonial Moreton Bay and the world that my characters inhabit in the mid-1850s. With the permission of a Senior Elder, I wrote a young Ngugi woman called Nita. She’s an orphaned Moreton Island woman who works for the Petrie family, who consider her their adopted daughter. At no point in my novel do I express a wish that Nita had died as a three-year-old rather than grow to womanhood.

Also with permission from Elders, I created an older woman character, Wongarra, whose Yuggera husband is the leader of the Kurilpa clan at South Brisbane. Wongarra is a woman and a leader – not a hag; and she speaks her language with fluency and intelligence as she lives according to sovereign Yuggera Law.

And thirdly, with the blessing of Senior Yugambeh Elders, I created my brave and clever hero, Mulanyin, a youth from Nerang Creek on the Gold Coast. He’s a visitor to South Brisbane who falls in love with Nita and dreams of returning home with her to be an independent married man, fishing with his own whaleboat. Mulanyin is not even remotely ‘subhuman’. Nor do I have him murdered by a comic madman for humorous effect. My young adventurer is displaced by history. He finds a new way to belong with Yuggera people and, despite experiencing tragedy, makes a new home in these people’s Country, where his legacy is ongoing.

Tom Petrie could arguably be called an honourable ‘pioneer’ of Meganchin/Brisbane, and Petrie, too, is a central character in my novel. But a colonial-era character with ‘the true hero stuff?’ That description belongs only to Mulanyin of the Yugambeh.

This is an edited extract of a speech given to the Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research on 14 October 2021. You can read the first extract from Edenglassie in Griffith Review 76: Acts of Reckoning.

References

Collingwood-Whittick, Sheila (2006), ‘Mrs Roxburgh’s Passage from Lady to Lubra: Racial stereotyping and the fantasy of indigeneity in A Fringe of Leaves’, in Sturgess, Charlotte (ed.), The politics and poetics of passage in Canadian and Australian literature, Nantes: CRINI, May 2006, pp. 39–56

Hadgraft, Cecil (1959), Queensland and Its Writers: 100 years, 100 authors, St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Lumholtz, Carl (1889), Among Cannibals: An Account of Four Years’ Travel in Australia and Camp Life with the Aborigines of Queensland, online at https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/among-cannibals/chapter-vi/322CA580BF91EF5F2EE7ED265313BF07

O’Doherty, Eva (1862), ‘Queensland’, online at https://www.oldqldpoetry.com/eva-mary-odohertyv/queensland

Ørsted-Jensen, Robert (2011), Frontier History Revisited: Colonial Queensland and the ‘history war’, Brisbane: Lux Mundi Publishing

Platt, Len (2008), ‘“Altogether better-bred looking”: Race and romance in the Australian novels of Rosa Praed’, Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, no. 8, pp. 31–44, online at https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/JASAL/article/viewFile/9732/9620

Praed, Rosa (1885), Sketches of Australian Life: Black and White, online at https://adc.library.usyd.edu.au/data-2/praaust.pdf

Praed, Rosa (1915), Lady Bridget in the Never-Never Land: A story of Australian life, London: Hutchinson.

Praed, Rosa (1902), My Australian Girlhood: Sketches and impressions of bush life, London: T Fisher Unwin.

Stephens, James Brunton (1885), ‘A piccaninny’, online at https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/piccaninny

Wallis, Lynley A, Burke, Heather & Dardengo, Mia (2021), ‘A Comprehensive Online Database about the Native Mounted Police and Frontier Conflict in Queensland’, Journal of Genocide Research, DOI: 10.1080/14623528.2020.1862489

Share article

More from author

On ‘The Seven Stages of Grieving’, by Wesley Enoch and Deborah Mailman

GR Online IS IT POSSIBLE to feel too much? For millennia, stories from around the world have had as their explicit task the expansion of the...

More from this edition

Being here

MemoirBACK IN 2015, when we were getting the local language work going here at the Aireys Inlet Primary School in Mangowak, every Monday morning...

Last rites

Memoir I COLLECT MY father on a hot Friday morning from a funeral home in Preston. He’s waiting for me in a shopping bag, housed...

Glitter & gold

PoetryListen to Sachém Parkin-Owens read his poem ‘Glitter & gold’ accompanied by world-renowned beatboxer Tom Thumb. We need action Not condolences Far too long we marched, danced and died Screamed, starved and...