The ship, the students, the chief and the children

Defying the fossil-fuel order

Featured in

- Published 20240206

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-92-4

- Extent: 204pp

- Paperback, ePub, PDF, Kindle compatible

UNDER A WARM blue morning sky unevenly patched with ragged strips of grey and white, a crowd of about a hundred people stands on a concrete wharf in Port Vila. We are waiting for the arrival of Greenpeace’s flagship, the Rainbow Warrior, which is visiting Vanuatu for the first time in many years. I’ve been onboard for various legs of the iconic vessel’s current journey through Oceania, but on this occasion I’m among the land contingent.

Standing closest to the waterfront, a muscular middle-aged man to whom I’ve just been introduced, the Honourable Chief Timothy, blows a conch shell with enormous force, the low note resonating across the quay like the bellow of a large mammal. The honourable chief has close-cropped silver hair and beard, and although bare-chested and footed, he is heavily decked out with armbands, chunky anklets, an over-the-shoulder basket bag, a prominent necklace of massive polished tawny-brown spherical seeds and a bark-cloth belt that is holding up a bright-green skirt of leaves descending to his shins. As the Rainbow Warrior gets closer, Honourable Chief Timothy waves the ship in, swinging a sash of woven plant fibres in a round beckoning motion and calling out in his deep chant-like voice: ‘Welkam home, Greenpeace! Come home! Our people have lots to tell you! Our mothers, our fathers, our people, our government – we have things to tell you!’

This is no supplication to be heard, but a generous invitation that evinces the confidence of sovereign prerogative. The shouts are a reminder of the bonds between Greenpeace and the peoples of the Pacific island nations, strong ties that arise from shared history and allied purposes. We are being gathered before venerable authority, called to bear witness not as bystanders but as heralds drawn home to be enlightened and revitalised before being sent forth on renewed assignment.

Honourable Chief Timothy repeats versions of the greeting as the ship pulls in. Once more the conch shell sounds; again the honourable chief shakes the sea and sky with his holler.

The latest incarnation of the Rainbow Warrior – the third vessel to bear this name – has arrived in the South Pacific to support a campaign of epic vision. In 2019, in a university classroom in Vanuatu, a group of students began earnestly discussing with their teacher how international law might be better used in the existential struggle against climate change. The extraordinary objective that was eventually agreed on was to secure a strong advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice in relation to states’ obligations to protect the human rights of current and future generations from the impacts of climate change. A new organisation, the youth-led Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change, was established to carry the case forward and has since forged collaborative relationships with Greenpeace and other civil-society allies to help build impetus around the world.

Improbably, this audacious youth-led stratagem has already achieved success, first securing unanimous support from the nations of the Pacific Islands Forum (which includes Australia) and then winning consent referral from the United Nations General Assembly to the International Court of Justice – the first time this has occurred in UN history. The case is due to be heard in 2024, and the Rainbow Warrior’s mission is to bring attention to the litigation, to engage in the practical business of documenting impacts, and to build the political momentum vital to securing participation from states party to the hearing. In addition to Port Vila, the ship will visit Erromango in Vanuatu, Funafuti in Tuvalu, and Kioa, Rabi and Suva in Fiji.

Even the desiccating quality of legal language can’t mask the almost mythic dimension to this enterprise: here, in the middle of the world’s greatest ocean, on the edge of our collective ecological precipice, the children of some of the most climate-vulnerable communities on the planet are offering stunning leadership, seeking justice from the highest court in the world for all who are oppressed by fossil-fuel corporations.

THE ARCHETYPE OF tyranny is the rule of the lone despot, embodied in the likes of the mad emperor, the wicked king or the uniformed dictator. Such tyrants hold capricious authority over the unfortunate populace subjected to their fiat, a rule invariably exercised through an apparatus of terror. In both real life and fiction, autocracies of this kind tend to be brutish, with explicit symbology and rhetoric reinforcing the leader’s right to absolute supremacy.

Yet the tyrannous application of power doesn’t require a vicious potentate. Tyranny can also function amorphously, appearing in distributed and surreptitious forms that are nonetheless still manifestly pitiless.

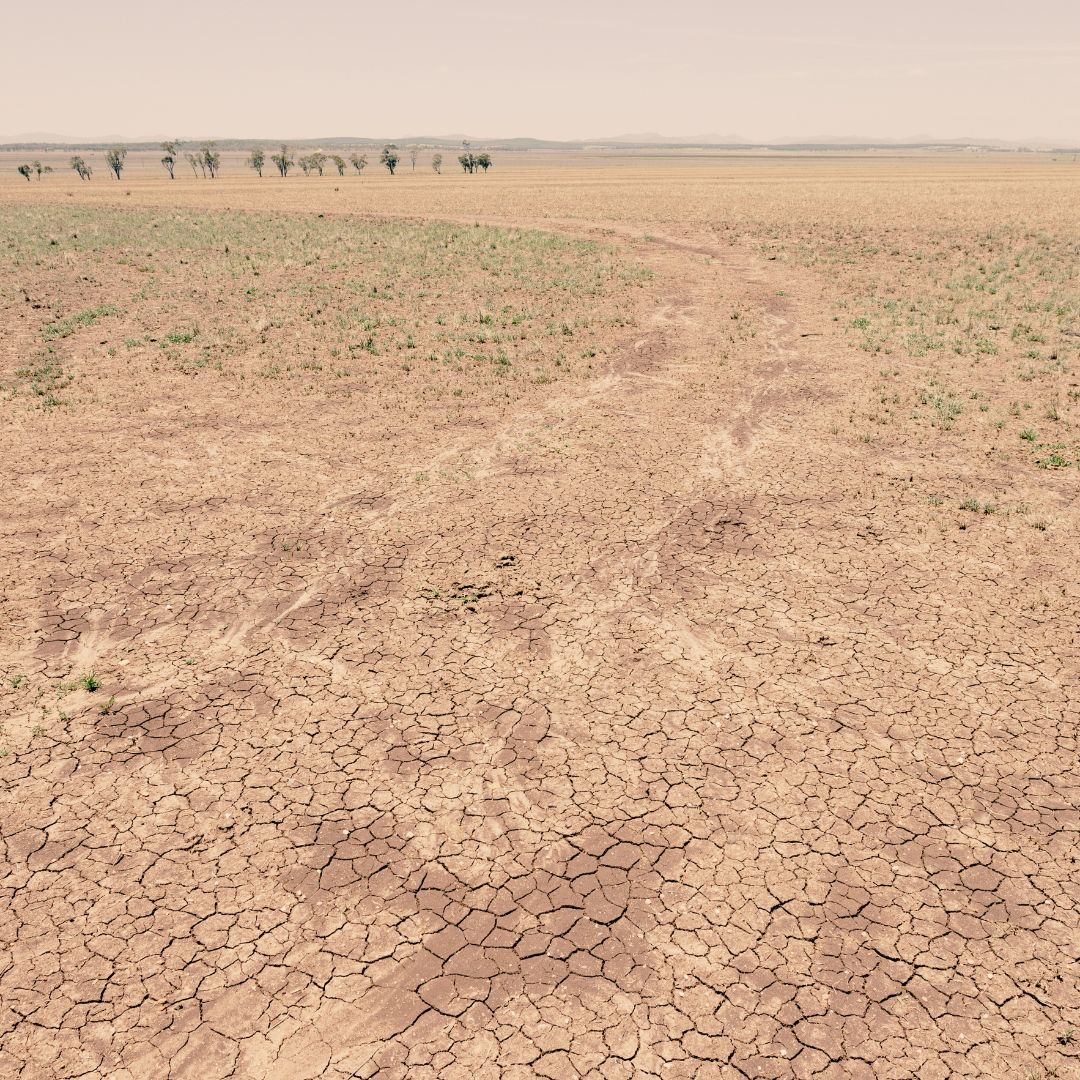

In terms of political effect, climate change amounts to systemic domination of this kind, working through a complex web of diffused decision-making to inflict ‘untold suffering’ (as it was described in a public letter signed by 11,000 scientists) on hundreds of millions of people, and destroying cultural and ecological heritage on a vast scale.

The primary driver of global warming is the extraction and burning of coal, oil and gas, activities that continue despite the consequences for human beings and the wider environment. I have described elsewhere the system of power that authorises this as the ‘fossil-fuel order’, consisting not only of coal, oil and gas companies and their elected apologists but of the greater mass of economic, political, social and cultural institutions and power relations that sustain these corporations.

The tyranny of climate change is thus not directed by any one central figure but is enacted through a multitude of individual and organisational decisions that permit the fossil-fuel order to continue to expand and thrive despite hideous repercussions. In April 2022, UN Secretary-General António Guterres described any investment in new fossil-fuels infrastructure as ‘moral and economic madness’ contributing to putting humanity ‘firmly on track towards an unliveable world’.

‘How must it feel,’ Amitav Ghosh asks in The Nutmeg’s Curse, writing of genocidal violence in what are now Indonesia’s Banda Islands, ‘to find yourself face-to-face with someone who has made it clear that he has the power to bring your world to an end and has every intention of doing so?’ The direct threat of extermination described by Ghosh contrasts with the polite ordinariness of the vast majority of the fossil-fuel order, embedded within the fabric of late-capitalist life in the developed world.

Take, for example, a company like Woodside Energy, the proponent of the Burrup Hub – by far the most climate-polluting resource infrastructure development being proposed anywhere in Australia, threatening to unleash millions of tonnes of gas until as late as 2070. The threat to human life and nature posed by Woodside’s business strategy through the direct environmental impacts of this gas is undeniable, but the company remains countenanced within society, as if nothing is wrong. Woodside sponsors children’s surf lifesaving, the Fremantle Dockers AFL club, the University of Western Australia, the West Australian Symphony Orchestra and much else besides. The company’s CEO, Meg O’Neill, is a frequent guest speaker at marquee public events. At one of Woodside’s recent AGMs, staff gave out quaint little bags of ‘melting moments’ to shareholders, presumably without irony. The company’s website is laden with feel-good platitudes, such as ‘It’s only by working together that a better future comes to life.’ It is all cloyingly typical of big corporations. Yet despite the gluggy opacity of the language and the dense shroud of social legitimation, the truth remains that extreme climate damage driven primarily by the exploitation of fossil fuels by businesses like Woodside is now lacerating people and nature all over the world.

The tyranny of climate change also has a radical totality of scope. The rule of a tyrant is typically bound by the borders of the region in which they exercise control, and by the duration of their reign. Climate change, though, is of an altogether different geographic and temporal character, because the atmospheric parameters for life on Earth are inherently ecumenical and many of climate change’s consequences are irreversible.

In George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, the indelible image of the future is ‘a boot stamping on a human face – forever’. The absolutism of runaway climate change threatens a variation of this nightmarish prospect. Although never the stated business intention, the result of continuing fossil-fuel expansion is the shoe of the fossil-fuel executive being ground into the face of every person on Earth, every baby not yet born, and upon the flesh of every living thing.

ALTHOUGH OFTEN ENGAGED in direct interventions to prevent environmental wrongs, the Rainbow Warrior is on this occasion busy with the work of campaign diplomacy. The ship will stay in Port Vila for a couple of days, hosting dignitaries, acting as a focal point for society events and holding booked-to-capacity ‘open boat’ visits for the local community.

One of the highlights of the program is a cultural exhibition held on the ship’s helideck curated and presented by Anjali Sharma. In September 2020, Sharma was first-named among a group of young plaintiffs – memorably described by the presiding judge as ‘the Children’ – who sought to obtain a ruling from the Federal Court of Australia that the then minister for the environment, Sussan Ley, owed a duty of care to protect young people from climate change. Anjali is now studying for a law degree while working part-time in support of the Pacific-student-led campaign for climate justice.

In taking the case that now bears her name, Anjali brought the tyranny of climate change into sharp focus. Surely the Australian government could not be permitted by act or omission to inflict the mass cruelty of global warming upon the children of the nation?

Famously, Sharma and her co-plaintiffs won at first instance. The Honourable Justice Mordecai Bromberg wrote in his remarkable judgement:

It is difficult to characterise in a single phrase the devastation that the plausible evidence presented in this proceeding forecasts for the Children. As Australian adults know their country, Australia will be lost and the World as we know it gone as well. The physical environment will be harsher, far more extreme and devastatingly brutal when angry. As for the human experience – quality of life, opportunities to partake in nature’s treasures, the capacity to grow and prosper – all will be greatly diminished. Lives will be cut short. Trauma will be far more common and good health harder to hold and maintain. None of this will be the fault of nature itself. It will largely be inflicted by the inaction of this generation of adults, in what might fairly be described as the greatest inter-generational injustice ever inflicted by one generation of humans upon the next.

Infamously, Ley appealed and was successful, with three judges of the Federal Court overturning the decision, though nothing in their honours’ judgements questioned the science of climate change. Whatever the reasoning, the full court’s decision suggested the inviolability of the tyranny of the fossil-fuel order under Australian law. The ‘greatest inter-generational injustice ever inflicted by one generation of humans upon the next’ – an expression of extreme tyranny, if ever there was one – is currently being permitted under Australia’s legal and governmental system.

The efforts of people like Anjali Sharma and the Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change are driving the momentum of climate litigation across numerous jurisdictions around the world. The display brought together by Anjali on the Rainbow Warrior is an eclectic array of objects in recognition of this growing phenomenon, drawn particularly from various Indigenous cultures, arranged quite casually but with clear deference on the ship’s trestle tables. Among the presentation are cowrie-shell ornaments from low-lying Kiribati, a couple of chi ku cha (traditional tools for moving cactus) from the Caribbean island of Bonaire and woven mats from the Torres Strait.

Apart from their indigeneity, what these items have in common is that they have been given to the Rainbow Warrior by peoples whose futures are threatened by climate change and who are seeking recourse through the courts. These are artefacts from cultural defenders united in their fight against tyranny. They are a reminder that while the end of rule by a lone despot might be achieved through individual denouement, the decentralised nature of the fossil-fuel order means that its overthrow can only be achieved through hundreds of thousands of acts of resistance, of all kinds and sizes – some contesting within the system, others in the realm of civil disobedience – across the globe. It requires a networked defiance wrought of an ethical and political consciousness of the world we are losing, truth-telling about what the fossil-fuel order is doing, and resolute conviction in the enduring possibilities of action.

The power of the fossil-fuel order depends on foreclosing any kind of political and institutional decisions that would see societies break free from the malignant clamp of coal, oil and gas corporations. This power also depends on eliding alternative ways of seeing. In one sense, the whole of the political struggle against climate change can be understood as an effort to make corporate and political decision-makers see, such that they are required to act. For the powerful who have not acted as they should, climate change and the actions required to reduce emissions have long constituted what Slavoj Žižek (riffing off Donald Rumsfeld) described as ‘unknown knowns’: things they know but intentionally refuse to acknowledge.

In earlier stages of the political contest over global warming, the principal strategy of the coal, oil and gas corporations and their allies was straight-out denial of the seriousness of climate change. It is now clearly documented that these earlier bosses knew or reasonably should have known that the continued extraction and burning of fossil fuels would have dire consequences for people and nature, but they did not accede to this truth. However, over time, with reporting, science, activism, art and the experience of severe climate impacts by ordinary citizens, this denialism has been called out and has steadily given way to a different kind of ‘unknown known’. In this new phase, overt repudiation has been replaced with explicit acknowledgement, but this is made hollow by diversionary strategies to justify inaction, including the rhetoric of incrementalism, greenwashing and offsetting.

So it was that, in a masterclass of obfuscation, Woodside CEO Meg O’Neill solemnly told the National Press Club in April 2023 that ‘climate change is real’, before explaining why ‘we must be wary of the temptation to focus on just one objective’. The agnotological consequences of delay are largely the same as that of outright denial. What is known and now plainly admitted is still not ‘known’ in the sense of triggering behaviour commensurate with the implications of the knowledge. Our home is on fire and decision-makers like Meg O’Neill know this, but their intention is still to open vast new reserves of fossil fuels for infernal exploitation.

Yet this is not the majority view; for many years in Australia, one survey after another has found an overwhelming desire for greater climate action. The public is not the problem here.

AMONG THE GUESTS to the Rainbow Warrior introduced by Anjali Sharma is the Honourable Chief Timothy, who has returned to speak and bestow gifts. Later, the honourable chief talks privately with me and explains the significance of each of the items with which he has presented us, including a wooden statuette and an ornately woven mat.

‘Lastly,’ he says, ‘when I’m here welcoming the boat, I was wearing this.’ He proffers the necklace of polished round seeds from around his own neck. ‘I’ve been keeping it for more than ten years, and it’s a part of my heart. And I’m giving it to you. Hang on to it. And it will be a historical gift… And never forget the chiefs of Vanuatu and the government and all the children and all the mothers and fathers. Never forget them.’

There is nothing so generous as the giving of an obligation founded in trust. The honourable chief tells me directly to speak and write about what he has said and what we have seen in our time with the Ni-Vanuatu; Greenpeace must be carriers of the messages of culture and justice to the ‘big brothers’ and ‘big countries’ over the waves.

We shake on things formally, then embrace, then grip hands again. I feel the strength of the honourable chief’s shoulders and arms. He smiles, keeps talking and points upwards. Deep inside, I sense the welling up of jagged sentiment: grief and love, hope and resolution, fear and commitment. I experience an exhilarating transcendence of my rational senses. Sounds slow down, the big sky is a vast blue iris of unblinking scrutiny, and the light sea air has the force of time running in all directions and possibilities. I have a fleeting but immeasurably precious awareness of the unaccountable grammar of being.

In a few days the Rainbow Warrior will sail away, bearing Honourable Chief Timothy’s presents along with the rest of the cultural objects, talismanic in the face of the climate emergency. I thank him effusively for the deep honour and respond that Greenpeace accepts his gifts with heartfelt gratitude, and that we will draw strength from them. ‘We’ll fight,’ he finishes by saying. ‘God be with us all.’ And secular though I am, I welcome this benefaction of providence uttered in the spirit of shared purpose – an expression of undying resolve, premised on universal love, that through our shared creativity and tenacity, we may yet secure the future of the world from the tyranny of the fossil-fuel order.

Postscript: As this article was being prepared, news came through that Honourable Chief Timothy had died suddenly of a heart attack. Although I met him only briefly, his passing feels like a staggering loss. The honourable chief is survived by his wife, Annemarie Andrew, eight children and six grandchildren, to whom I extend my condolences and deepest sympathies. The words of Honourable Chief Timothy will not be forgotten.

For details on the campaign to secure an opinion from the International Court of Justice on the obligations of states to protect human rights from climate change, please visit the website of the Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change or the website of Greenpeace Australia Pacific.

Image credit: Getty Images

Share article

More from author

Inside the dark tower

Thinking of what is gone, I pause on the bridge and look back. The windows and sleek curvature of Woodside Karlak now give the impression of smooth scales, sliding upwards towards the encroaching night. It is hard not to appreciate elements of the architecture, even when you know what is being sacrificed as a consequence of the decisions that take place behind the darkened glass of the great tower.

More from this edition

Nostalgia on demand

Non-fictionHow then do we approach a circumstance in which it is possible to consciously curate those memories and sense impressions, such that they become mere features of our ‘profile’? Or one where third parties, having gleaned enough data to know us better than we know ourselves, can supply those memories and impressions for us?

Pentax ME Super

PoetryHistory is a heavy handful and a sore neck, but it is safer than memory.

Glitter and guts

Non-fiction RIGHT NOW, I am obsessed with the past. My debut novel is finished and ready for publication, and I am wrestling with the fear...