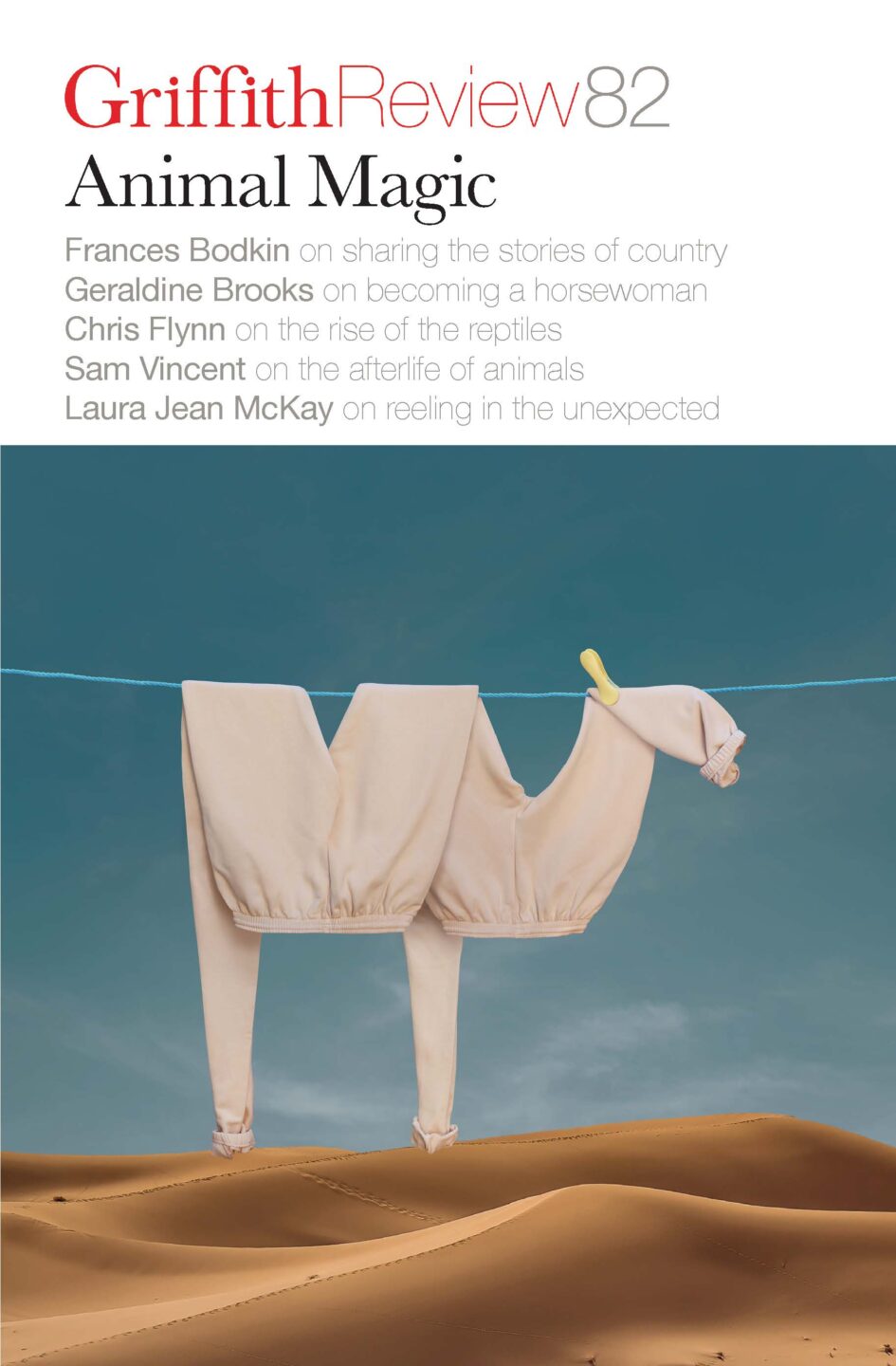

Featured in

- Published 20231107

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-89-4

- Extent: 208pp

- Paperback, ePub, PDF, Kindle compatible

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

A tough sell

While mine is a unique pathway to publication, the length of time it’s taken, the number of rewrites I’ve completed, and the thinly (and sometimes not-so-thinly) veiled racism that I’ve experienced are not unique when it comes to the journeys of authors who are First Nations and People of Colour (FNPOC).

More from this edition

Rise of the reptiles

Non-fictionIn tandem with these plans to cultivate meat in laboratories, bioscience companies in Europe, North America, South Korea and China are currently working to resurrect living, breathing examples of the woolly mammoth, thylacine and dodo. While this may seem foolhardy, the intention is to restore nature’s balance by rewilding animal habitats and damaged ecosystems.

A life with horses

In ConversationIn 2011, I was invited to a writers’ retreat in Santa Fe. It was held on a lovely old ranch with beautiful horses – Western Paints, Appaloosas – and one of the wranglers noticed me admiring them and invited me on a trail ride. It was an ecstatic experience.

Fish

FictionHe hasn’t caught one in twelve years or more, not since just before Ritchie – Hayley’s oldest – was born. The deboning alone can take half a morning and you have to strip that tail to its cartilage very carefully because there’s a layer of green resin, bitter. In small doses it ruins the meat; poisonous if you eat too much.