Featured in

- Published 20230502

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-83-2

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

About the author

Mark Tredinnick

Mark Tredinnick OAM is an award-winning poet, essayist and teacher of writing. He is the author of eighteen books of poetry and prose, and...

More from this edition

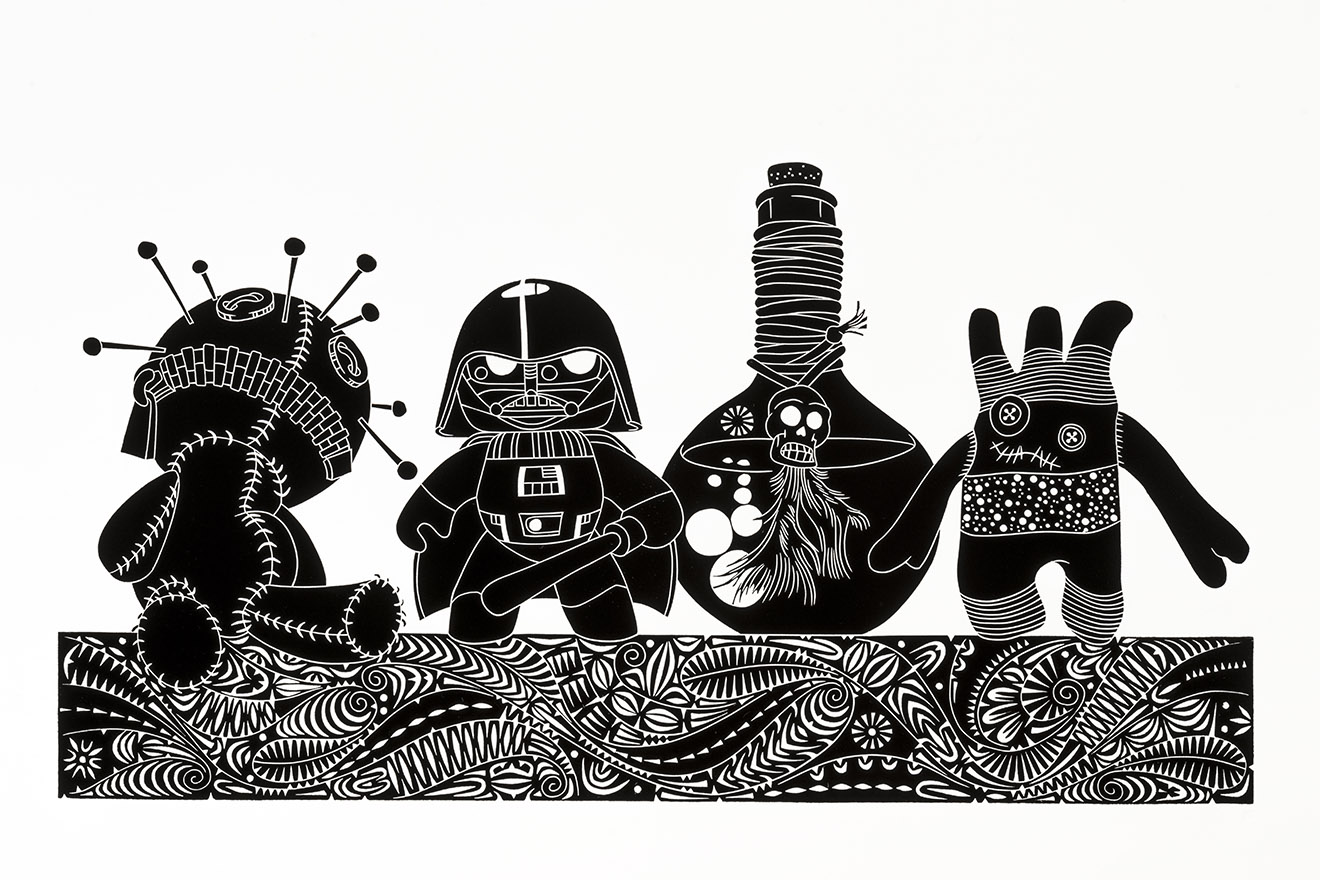

Pop mythology

In ConversationEven though I grew up on a small, remote island, I was still heavily influenced by television – particularly the sort of cartoons that would play on Saturday mornings, mornings before school, after school and so on. When it comes to DC and Marvel and all of those superheroes, for me that was ignited by my late grandfather Ali Drummond, my mother’s father, who had boxes of Phantom comics. Phantom was my early introduction to the strong, powerful male being who had supernatural strength and abilities.

New Scientist

PoetryA body we can read and understand. If only I could put you under a microscope and transform you into a symbol to unite our disciplines: the communication phage.

A Martuwarra Serpent stirs in its sleep…

Non-fictionAboriginal people are usually confident in the enduring nature of knowledge (not just belief) because that other mob down the road has the same story, or a similar one. It is a multispecies and layered story, and that is precisely what makes it creative, unlike so much of continuing Western materialist ideas and practices.