Edition 89

Here Be Monsters

- Published 5th August, 2025

- ISBN: 978-1-923213-10-4

- Extent: 236pp

- Paperback, eBook, PDF

Portent, symbol, metaphor: From the werewolf to the Pale Man, from Count Dracula to the (far more sinister) emotional vampire, monsters of all forms have offered us ways to express and exorcise our fears for thousands of years.

This edition of Griffith Review surveys beasts and bogeymen past and present, real and imagined, to peel back the layers of our social and cultural anxieties. What are we most afraid of? When is monstrosity alluring rather than frightening? And what form might the monsters of the future take?

Edited by Carody Culver with contributing editor Lisa Fuller.

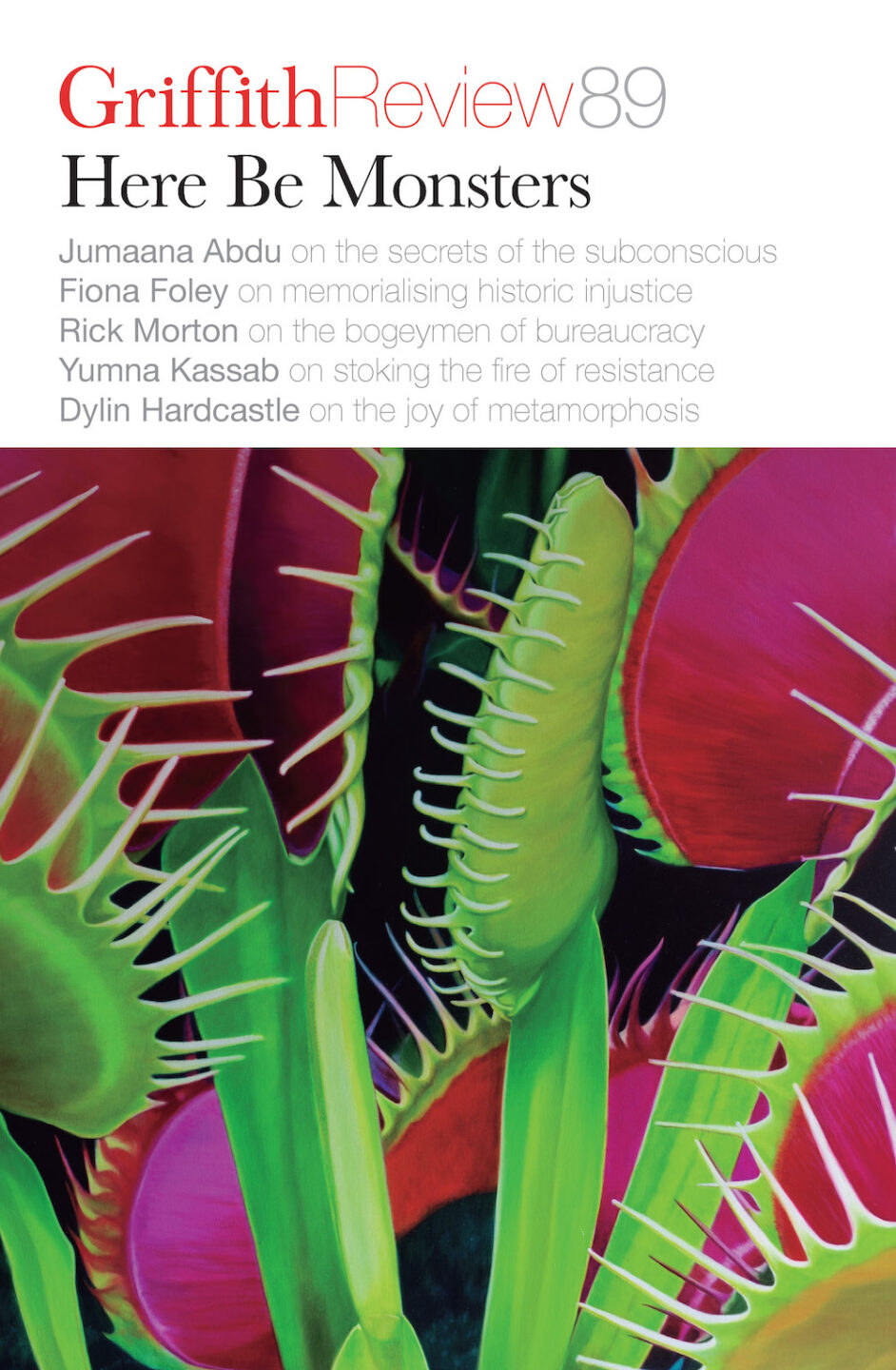

Cover image: Jason Moad, Temple of Venus (2022), oil on linen, 198 x 111 cm, courtesy of the artist.

In this Edition

Operation Totem

In the 1950s and 1960s, hundreds of atmospheric and underground tests were conducted in Australia, with devastating consequences for First Nations peoples and for the military personnel involved in the tests. And yet the debate about Peter Dutton’s plan to put Australia on a nuclear track barely mentioned this calamity, or indeed the deep antipathy towards all things nuclear to which it gave rise. Struggling to put Dutton’s policy in context, one looked in vain for even a passing reference to Dr Helen Caldicott, Moss Cass or Uncle Kevin Buzzacott; to the Campaign Against Nuclear Energy or the Uranium Moratorium group; to the seamen’s boycott of foreign nuclear warships in Melbourne in 1986; to the massive antinuclear marches of the 1970s and 1980s; to Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta and its resistance to the dumping of radioactive waste. Indeed, one looked in vain for any sense of nuclear as a uniquely dangerous technology, or of the ‘deadly connection’ (as Jim Falk called it) between uranium mining, nuclear reactors and the development of thermonuclear weapons.

A nation’s right to remember

In a 2023 article published in The Guardian, the Australian War Memorial’s newly appointed chair, Kim Beazley, acknowledged, ‘We do have to have a proper recognition of the frontier conflict.’ In an interview with Beazley on the ABC’s 7.30, journalist Laura Tingle reported that of the 27,000 metres of new space in the expansion, the pre-colonial gallery, which includes the Frontier Wars, would make up less than 2 per cent, and asked, ‘Will that be sufficient?’ Beazley’s reply was, again, ‘we need to have that recognition around the country’, while he emphasised that other institutions should play a role in the telling of Australia’s Frontier Wars. A charismatic sidestep.

The coward

At the beginning of my research, I knew little about Anne. I knew that my aunt had been married to an Anglican reverend. I knew she was Dad’s half-sibling, from my grandfather Staniforth Ricketson’s first marriage. I knew that she lived in the country at Mount Macedon. The final thing I knew for certain: my aunt died a sad and violent death. She perished on 16 February 1983, the night of the Ash Wednesday bushfires. Her husband, the Reverend Bill Carter, drove away from their cottage without her. In his panic, he left his wife behind and saved himself as the flames closed in.

Stories of cowardice, unlike those of courage, make us deeply uncomfortable. Coward is a label we generally affix to those we call monsters: terrorists, paedophiles, predators. But cowardice does not just exist at the extremities of behaviour – it is both more quotidian and more human than that.

Man’s Labyrinth

Max Weber foresaw the iron cage of rationalisation coming for us all: that industry and its social institutions would become so technically efficient that a worker would become a ‘specialist without spirit’ and a consumer a ‘sensualist without heart’. People could have everything they’d ever wanted, in theory, but the cost would be their humanity.

Weber conceived of this as a prison of capital when workers were in factories and those factories increasingly required employees to take on smaller and more specialised roles. This stretched into the bureaucratic sinew of large businesses and corporations, naturally, and into the administration of states, municipalities and even sufficiently large Zonta clubs.

The fire this time

When I think about this period now I see that my life has been one long exercise in walking back from a bridge and talking down a fire. The bridge has always been what is the point of this and the fire has always been an overwhelmingly destructive energy that threatens to consume everything. One is an anger turned inwards while the other is directed outwards, the building is burning and there is nothing to save in all of humanity.

One continuous showdown

The driver picks me up from Mumbai airport and drops me off in front of the hermitage entrance, at the foothills of an ancient fortress. Decades earlier, when the guru and his wife purchased the land, they kept panther-watch at night. I’m in the right place, aware of my own monster still prowling about

The other side

Metamorphosis is violent, and isn’t this radically beautiful to transform this body, to shape and alter it, to decay in order to live? To die in order to flourish? I can’t tell you how excited I am to expand. To walk in every direction of this life. Shoulders back and chest stretched wide in sunshine. No longer hunched and hiding. But full bodied and glorious. I hope I’ll be more sure, that I’ll speak more from the chest, that I’ll be more honest, when there’s less to hide behind. My future has never felt so bright.

Imperceptible signs

One day, I took a necklace with a hollow silver heart from my jewellery box. I gave it to my sister, telling her that this was a special necklace. Whenever she wore it, she would be protected from ghosts. She wouldn’t be able to see them anymore. She wore the necklace constantly and for the next week or so she slept peacefully through the night. But soon after the ghost returned. She would now appear in the hallway and this time she had a man with her. And so it continued.

Ourself behind ourself

There are moments in my life I look back upon in awe and disbelief. Other times, new consciousness allows me to view dimly lit tracts previously incomprehensible and menacing with luminous epiphany. It seems to me that in those moments another woman or girl was acting in my place, withholding my motivations, protecting me from being an accomplice. This shadow actor, the extent of whose influence I am never fully aware, sometimes passes through my peripheral vision, filling me with unease. What ambush might she stage if I do not keep watch? What confession might she murmur while I am asleep?

Spectres of place

In September 1992, bushwalkers carrying out an orienteering activity in Belanglo discovered the remains of two mutilated female corpses covered in leaf litter. This led to a police investigation that was unsuccessful. When the investigation was closed leaving the victims still unidentified, Bruce began spending some of his time in the forest looking for evidence that might help solve the mystery. He knew the forest well from collecting firewood there to fuel his kiln and had an extensive collection of maps showing the fire and walking trails that covered the whole area.

Inside the dark tower

Thinking of what is gone, I pause on the bridge and look back. The windows and sleek curvature of Woodside Karlak now give the impression of smooth scales, sliding upwards towards the encroaching night. It is hard not to appreciate elements of the architecture, even when you know what is being sacrificed as a consequence of the decisions that take place behind the darkened glass of the great tower.

A discovery of witches

Unlike the patriarchal and monotheistic Abrahamic religions, paganism is structurally non-hierarchical – although covens (groups or meetings of witches) tend to be nominally led by a high priestess and high priest – and, in the words of influential English Wiccan Vivianne Crowley, pagans ‘worship the personification of the female and male principles, the Goddess and the God, recognising that all forms of the Goddess are aspects of the one Goddess and all Gods are aspects of the one God’. There is no holy book, messiah or central administration, and its ethos is fundamentally exultant – celebratory of the body, nature and the divine.

To clarify a common misconception: most pagans neither believe in nor worship Satan, a figure rooted in Judeo-Christian traditions rather than nature-based spiritual paths. The conflation of pagans with ‘devil-worshippers’ dates to the twelfth century and is a product of the Catholic Church’s campaign to quite literally demonise the horned, cloven-hoofed gods – Pan, Herne, Cernunnos and others – central to the pre-Christian spiritualities the Church was intent on suppressing.

The witch trials of the early modern period, where accusations of devil worship were frequently levelled against those, usually women, who practised folk magic, herbalism or traditional healing (or, in many cases, had simply drawn the ire of a relative or neighbour), reinforced the association between nature-based religion and Satanism. As the historian Ronald Hutton observes in The Witch: A History of Fear, from Ancient Times to the Present (2017),the standard scholarly definition of ‘witch’ has come to denote, in the words of anthropologist Rodney Needham, ‘someone who causes harm to others by mystical means’.

Meatspace

IN THE EARLY stages of a relationship, I suppose there’s always a tension between how much to withhold and how much to disclose. An incremental filling in of history. I was in the unusual position of only having so much control over this process, namely because I’d published an account of my long history of mental illness, its contents accessible to anyone who knew my name. Laid out in granular detail: an account of my self-destructive compulsions; my regular descent into trance-like episodes that could keep me captive for hours on end; my capacity to keep secrets; my many-sided shame. All my monsters, so to speak, there on the page.

The whole idea of dating terrified me in part because of what my body, on closer inspection, revealed about me. You didn’t need to be that far along into getting to know someone before they held your hand, or stroked your hair, but I found both of these prospects terrifying. My fingernails were mutilated; my hair was meticulously arranged to hide the fact I’d torn most of it out.

How to begin to explain what I’d done?

Agony aunty

Michelle always stank of stale cigarettes because back then you could smoke inside the casino. She always looked tired and her skin was almost translucent from being indoors all night and sleeping most days, but I thought she was glamourous. Vampiric, even.

I was never properly introduced to her. I was only told to call her aunty, that she was a friend of my mother’s and to do what she said.

Maiden, mother, monster

My son worries that a monster will come at night. This is a new concern of his, and I try not to connect it to his father’s absence. As I tuck him in, I tell him not to worry because the truth is monsters are very scared of mothers and won’t come anywhere near me. I’m too terrifying, I tell him, making him laugh. And cats too, I add, as ours curls at the foot of the bed, watching us. My son closes his eyes.

Grave years and the undead woman

MANY A MOTHER has found herself at the mercy of this false opposition between her needs (which are cast as selfish wants) and the countless supposed needs of her child. And whenever she falls short – gives in to anger or frustration or impatience, or the more convenient but ‘wrong’ way of doing things – she undergoes a transformation: Lucy Westenra, but yet how changed. Her fangs protrude, her nails lengthen. Clutched to her breast is a child she is harming, a child not rightfully hers.

Instructions for killing monsters

I do know this: Never in the history of the world has any monster been defeated with fear. (Literally, never. I checked.) Ultimately, the only shields against the powers of destruction, death and evil are the qualities that come under the banner of love, which is the bright day to fear’s night.

One telekinetic Wednesday

THE JOB, IT turned out, was mostly folders. Tricoloured, triaged, in need of fresh sticky flags. Each weekday at 8 am I tapped my government pass and rode the elevator to the eighth floor, where I had a desk in a converted cupboard and...

The Mountain

STANDING HIGH IN the landscape, the Mountain has always been there. Listening, watching, teaching, arranging the flow of the winds, giving life and sustenance to Country, directing the River’s course and cradling the bones. The Mountain held the stories of the people, and the...

The body

The LORD prepared a great fish to swallow up Jonah,and Jonah was in the belly of the fish three days and three nights. – Jonah 1:17 THE VERANDAH OF the house is dark for the time of day. Miranda moves her weight from one foot to...

Gallows humor

THE TOWN’S FLOWERS have set seed in the late-spring wet hot air, as the land prepares for the rains. It is nearly hatching time for the gall wasps. Swollen, pregnant growths deform the limbs as larvae gnaw and suck at the sap. Soon, they...

Red

WHEN SHE HEARD the knock on the bathroom door, she jumped. Her husband rarely interrupted her while she was inside. ‘What is it?’ she asked. ‘I seem to have had a little accident. Can you hurry up?’ ‘Hold on.’ She got herself presentable and washed her hands....

victoria pedretti is my sleep paralysis demon

act one i try to write a happy poem but i am bed rotting, watching victoria pedretti be hauntedby her demons. i try to write a happy...

I Cavalli after Bella Li’s ‘Il Bambino’

At the beginning of all motionthe horses galloped towardthirst. A land steeped in droughtexcited them. In each countrydecayed the myth of origin, ineach people there was nothingleft of people at all. Carrion birdsperched on their flanks spokein tongues, saying the last manwill find this...

LIFE

And Hyperion’s edict went forth thus: take the ground pig, sleeve it in its guts, build a blaze on the beach of kings. The benevolent authorities set out concrete rings. First 50, then 500, to say thanks and make amends. Up to 1500 now on holiday weekends. A Titan demands...