Women’s work

Investigating leisure and gender through time

Featured in

- Published 20230801

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-86-3

- Extent: 200pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

‘EIGHT HOURS’ LABOUR, eight hours’ recreation, eight hours’ rest.’

This is what the labour movement fought for. Yet where in this deceptively simple calculation is the unpaid work of care for the self and others, which is growing ever more complex in the digital age? If the gender relations of labour and leisure remain invisible, what are the social costs for women?

Answering this question means going all the way back to the heady days of the Whitlam government – specifically back to 1972, when the first Commonwealth Department for Tourism and Recreation was established. Prompted by concerns from researchers, public commentators and policymakers about the problems that would arise from a technology-fuelled ‘leisure society’, this was the moment when the role of leisure in Australian life became a political concern in the public imagination.

It was also the era of TV, which gave Australians access to important current events and greater exposure to American culture. The very early days of personal computers, mobile phones and the popularity of portable music listening devices were changing the ways people related to their environment and interacted with the world. For the first time they no longer had to rely on traditional post to send and receive messages, while music could be consumed on a bus or in a park.

In the midst of all this change, the state stepped in to help. As Whitlam famously declared in his 1972 election speech:

There is no greater social problem facing Australia than the good use of expanding leisure. It is the problem of all modern and wealthy communities. It is, above all, the problem of urban societies and thus, in Australia, the most urbanised nation on Earth, a problem more pressing for us than for any other nation on Earth. For such a nation as ours, this may very well be the problem of the 1980s; so we must prepare now; prepare the generation of the ’80s – the children and youth of the ’70s – to be able to enjoy and enrich their growing hours of leisure.

This new political imaginary positioned the state as central to cultivating leisure freedoms through individual choice and to devising social and economic policies that would combat inequality in the pursuit of opportunity. Around this time the women’s movement was demanding equality in the workplace, so leisure was not high on the agenda – it was yet to be understood beyond the heteronormative realm of home and family, let alone addressed as a public issue.

In 1975, the Whitlam government funded three substantial studies that would change this: Australians’ Use of Time; Leisure, An Inappropriate Concept for Women? and Leisure Activities Away from Home. Using a range of methods, such as time-use diaries, surveys and one-on-one interviews, these studies sought to understand the current state of play and where the government might intervene.

All three revealed some of the notable gendered inequalities in Australian society, particularly in the areas of unpaid domestic and care work. The time-use study was an important feature of government-funded research and was conducted regularly until 2006, when it went on a sixteen-year hiatus due to funding cuts. Drawing on interviews with 1,492 people, it showed that women did more unpaid domestic and care work than men, regardless of whether they were also in paid employment. Leisure Activities Away from Home presented findings from a survey of 18,000 adults, revealing a significant gap in the arena of sport and water activities: women participated and spectated much less than men. Other activities measured in that study included attending entertainment, socialising and organising meetings, all of which were slightly more likely to be done by women than men.

These studies also revealed the complexity of planning for and governing leisure time. Leisure: An Inappropriate Concept for Women? included insights from interviews with 834 women – a huge number for this type of data. It concluded that even for those women who had some leisure time available to them (which was only those who didn’t have paid employment), very few enjoyed leisure activities outside the home – many even expressed the view that it wasn’t right for women to have interests outside the family.

This public investment in research positioned Australia as a pioneer in developing and deploying time-use data to inform policy and planning, with surveys and time diaries building a picture of how diverse Australians spent their days. Questions raised by this research, and concerns about the best use of ‘expanding leisure’ in light of new technology, were becoming a key focus for the field of leisure studies, which emerged in universities to provide additional data, theoretically informed concepts, education and policy recommendations. For the next few decades, Australia was a leader in the field, garnering an international reputation for innovative research and strong impact on public policy and community programs.

Meanwhile, government-funded studies and independent projects raised important and complex questions about women’s role in society, their rights to leisure and the role of the state in both. For academics and students of leisure studies, this wasn’t just a case of arguing for the benefits of leisure – it was also about seeking to reconceptualise gender and leisure to create a more inclusive and equitable world. But how much progress have we really made towards this goal?

IN THE 1990s, increasing fiscal and social rationalisation shifted responsibility for leisure from the state to the individual and from the public to the private sphere. Leisure studies, with its emphasis on providing research and data to inform leisure quality, accessibility and access, was rationalised to enhance the ‘bottom line’ of universities that were now attuned to the pragmatic desires of industry sectors. This trend for specialisation led to degrees in sport management, tourism management, event management and hotel management – and although there are some academics who still bring a more holistic perspective to understanding leisure as a broad and nuanced concept, that critical edge and concern for equality and quality of life (and leisure) has been replaced by a focus on the ‘customer experience’.

This idea of customer experience has penetrated more broadly, too – the individual, previously conceived of as part of society, has been transformed into a ‘consumer’ who receives services (from both public and private providers); the state is involved in more complex relations of power as we citizens are urged to govern our own ‘freedom’. But this market-driven conception only reinforces inequalities and the increased commercialisation of leisure.

Fast forward to the present day of global capitalism and digital leisure lives. The technologically fuelled ‘leisure society’ imagined by commentators has taken a very different course – life is now shaped by algorithms we cannot see, yet cannot escape. Today’s hypermediated leisure landscape is a complex mix of DIY enthusiasts, social-movement activists, lifestyle entrepreneurs and endless wellness products that promise health, fun and happiness. And in the midst of all this, women have become a significant market segment, urged to empower themselves in the pursuit of wellbeing as an individualised phenomenon. Research overwhelmingly tells us that women are overburdened with care for others. Yet instead of having their load lessened, they’re offered market-driven solutions and compelled to display a feminine aesthetic: pastels, candles, coffee, wine, self-help books.

These leisure practices fuel and are fuelled by an affective economy that paradoxically involves endless work on the self, often masquerading as leisure – the pleasures and demands of cultivating a digital identity, seeing and being seen across work, home and public spaces. Technology delivers us the rush and excitement of new things – gadgets, compulsions and connections that make us overlook the kinds of (un)freedoms they produce, despite what they might promise. Leisure freedoms and desires become articulated through a cultural psychology of market relations in which the glow of positivity obscures the complexities of inequality. Feminist cultural theorist Lauren Berlant describes this poisoned chalice in the opening of her 2011 book Cruel Optimism:

A relation of cruel optimism exists when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing. It might involve food, or a kind of love; it might be a fantasy of a good life, or a political project. It might rest on something simpler too, like a new habit that promises to induce in you an improved way of being. These kinds of optimistic relations are not inherently cruel. They become cruel only when the object that draws your attachment actively impedes the aim that brought you to it initially.

Technology promised us a leisure society, yet somehow it remains out of reach, just like the self-improvement and material success we’re constantly striving for. The ethos of ‘work hard, play hard’ has permeated our cultural consciousness.

For men, the health burden of this way of life often manifests as heart attacks and stress- and excess-related diseases. For women, higher rates of depression and anxiety reflect the impossible demands they face: not just ‘work hard, play hard’, but do the dishes, look good, be gentle, be kind, be caring – and do it all with a smile and for less pay.

Stepping off this high-speed treadmill requires a radical shift. And in 2020, a shift of sorts did come: a virus that set in train a series of events that would disrupt our normative assumptions about how life should be lived and how we treat those most vulnerable in our communities.

THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC turned our work, leisure and care relations upside down. It was also, coincidentally, the end of the sixteen-year hiatus for Australia’s time-use survey. Its return finally came about after almost a decade of calls from various sectors, including women’s groups, for the reinstatement of these important measures.

The 2020–21 time-use survey revealed that little had changed in the gendered division of life since the 1970s – although women’s leisure time had marginally increased, women still had less ‘free’ time than men and spent more of their days doing unpaid domestic labour, child/adult care and voluntary work. Other surveys conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic reported increased gambling losses, alcohol consumption, violence against women and children, and worsening mental health.

But the pandemic ushered in positive change, too. Previously impossible work changes suddenly became possible with a revaluing of flexibility. Our private and professional spaces became entangled in new ways: children, pets and plants appeared on Zoom calls from bedrooms and dining-room tables. Commuting ceased for those deemed unessential workers. And beyond the world of work, a walk in the park became a time for connection with nature, with our community, with our bodies. People moved interstate and to regional communities in search of better balance, different spaces in which to move and breathe.

COVID-19, like the social changes of the 1970s, shifted the discourse, raising questions about how we are to live when the digital tentacles of work reach far into our leisure and home lives.Who benefits from the organisation of life through (paid) work/leisure opposition? When the costs of holding on to normative practices became too much, different ways of valuing leisure time erupted. As we learnt in the 1970s, these questions about leisure have gendered implications.

For women juggling work, child/adult care, domestic unpaid labour and the imperatives for ‘self-care’, leisure is not the frivolous opposite to work. Rather, as feminist leisure studies scholar Betsy Wearing wrote, it is ‘a safety valve for sanity’. When home became work became school became a site of entertainment became everything, pressure mounted, on women especially, to hold it all together without having the time or space to explore their leisure lives.

WE HAVE COME out of the pandemic emotionally – and for some people physically – exhausted and anxious. Rates of mental ill health, particularly for women, have increased. The shared recognition of this ‘great exhaustion’ has, more than anything, made people reconsider leisure through a more political lens and as central to emotional wellbeing; it’s made them recognise that the state should hold some responsibility for working life, childcare and providing public spaces for enjoyment. Desire for change proliferates through social media – there are calls for more flexible work, slow technology, restful leisure, sleep hygiene, different care practices and greater childcare support, along with ways of connecting and reducing isolation and poor mental health. As we emerge from the isolation and exhaustion of the past three years, we have an opportunity to reconfigure individualistic conceptions of women and wellbeing.

Leisure may seem like a trivial topic to some, of little consequence and largely a private matter of consumption tastes. Yet without a deeper leisure ethos, life risks losing much of its meaning. The forces that constrain and limit what it’s possible to do (and how it’s possible to feel) can also be resisted through leisure practices that seek alternatives.

But what role should the state play in all this – and what role can it play? People’s ‘free’ time cannot be easily regulated, and addressing collective exhaustion cannot be shifted onto women as yet another thing on a never-ending to-do list.

One thing the state can do is recognise and respond to women in light of their complex and diverse roles. Women don’t all share the same consumer profile, and nor do we have the same needs and desires. Some women have children (or foster children), some don’t (by choice or not). Some women come from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, many experience disability and health conditions. Some women are trans. Some women are athletes. Some love crafting. Some thrive in high-performance work environments, others experience exclusion from the workforce and can’t find a place to call home. Some women love women. Some love men. And some aren’t interested in either. Most women need free, safe public spaces and subsidised services to be active, creative, engaged and connected. Our wellbeing depends upon it.

The Labor Government only this year recommitted to conducting regular time-use surveys, showing a willingness to self-examine key social patterns that profoundly impact individual and social wellbeing. This is important – if we don’t know about our inequalities, we can’t exercise the political will to effect change. However, the question of interpretation remains: what gets counted as leisure (or not), and whose contribution to all forms of work, leisure and care is valued? As the groundbreaking feminist economist Marilyn Waring noted in 1988, the gendered understanding of leisure needs an overhaul – the experience of time must be freed from feelings of guilt and obligation to others, allowing us to enjoy pursuits for their own sake. While we haven’t yet unshackled women from their obligations to others, we must acknowledge that gender inequities in leisure time continue to be tied to unsustainable care obligations This is an ongoing conversation for all of us – households, organisations and the state. Our future quality of life (and leisure) depends on it.

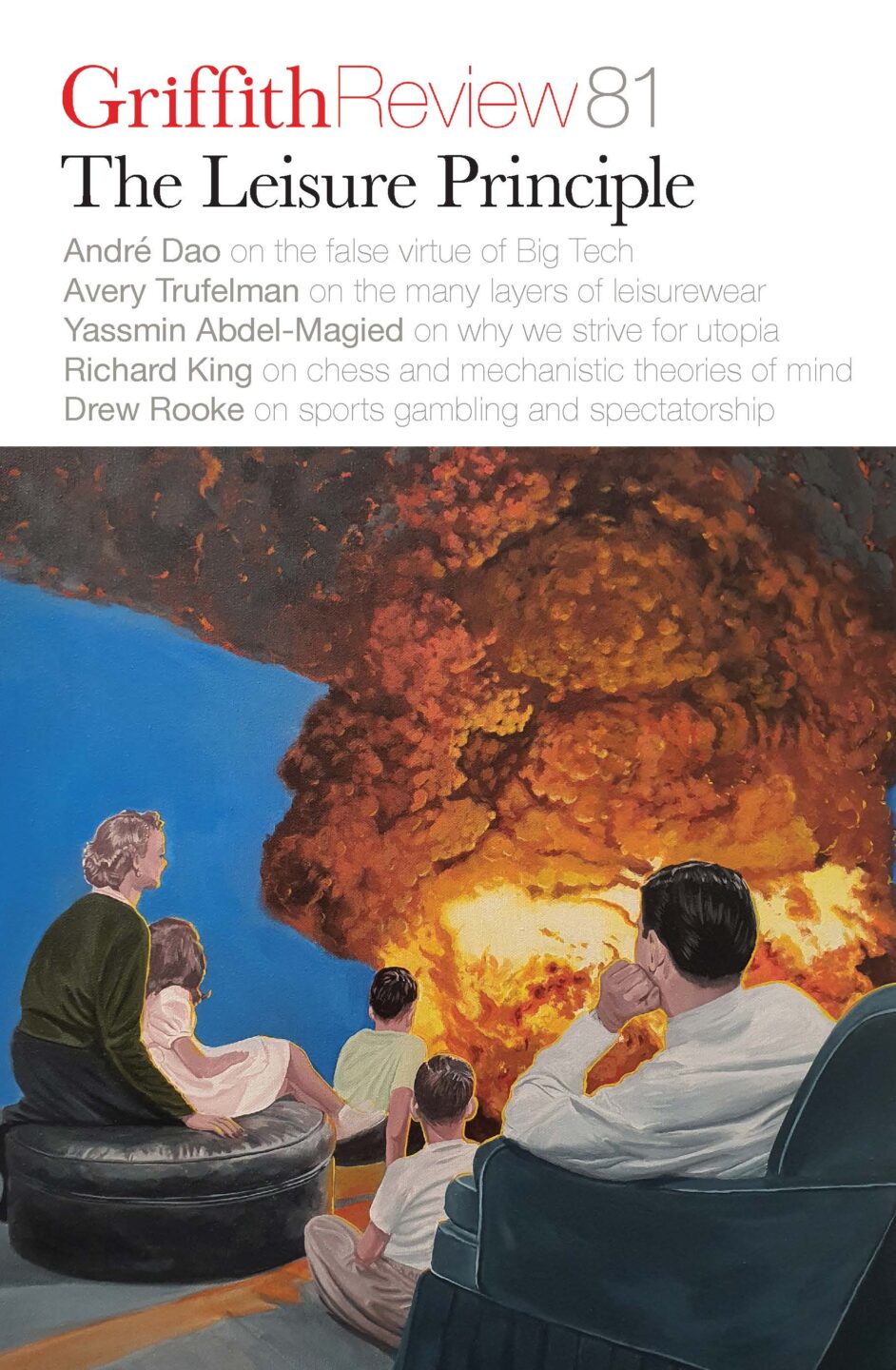

Image credit: Getty Images

Share article

About the author

Simone Fullagar

Simone Fullagar is a feminist writer and professor at Griffith University who lives on the unceded lands of the Yugambeh and Kombumerri peoples of...

More from this edition

Salted

FictionWe are absorbed in our work until we are not. Mostly we take breaks together, sitting outside in the sunshine waiting for our thoughts to settle, waiting for our lives to begin. Gus and I have both applied for the same scholarship. We’ll find out at the end of the month. Eve is organising a group show and wanted my latest painting as the centrepiece, but I won’t finish it in time, so I drop out. ‘I’ve got something ready,’ says Gus. Easy enough to find someone to fill my place.

Dressed for success

In ConversationHip-hop was about taking this mainstream look – a nice, acceptable, appropriate look – and, like, changing it up. Sampling it like it’s a song and turning it into something new. So when preppy emerged in mainstream white corporate culture, it started mixing with denim in new ways and mixing with sneakers in new ways and becoming a form of streetwear.

All work and some play

In ConversationI’m often hearing about odd jobs that musicians or performers had and how it’s tied to their identity. You read about Beat writers like Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady, who really identified with blue-collar people and railroad workers. After Kerouac got infamous, or famous, he went off to be by himself in a cabin in the forest as a fire lookout. So he went into a very solitary existence, and I like that kind of thing...