Why do you want to make things?

Prison arts education and decolonising systems

Featured in

- Published 20220127

- ISBN: 978-1-92221-65-8

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

ACCORDING TO THE United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF), Australia is ranked thirty-ninth out of forty-one high- and middle-income countries in achieving quality education.[i] How ‘quality education’ is defined may vary from high school completion rates to the impact students have on the world after they graduate. At the same time, researchers in the field of education seek to understand students’ experiences and to develop teaching practices that have the best possible outcomes. This is essential to translate how people learn and the benefits of this in relation to sociological experiences – or what might be described as the messiness of life itself.[ii]

One group of learners commonly overlooked in educational discourse is the prison community. Australia may not rank highly in the stakes of world-class quality education, but it is highly ranked in terms of overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples among its incarcerated. How might a focus on quality education in prisons lead to greater equity in the Australian social system? Can it help to address the issue of incarceration itself, which ultimately reflects a conflict with dominant social constructs and values? Can carceral arts point to ways to decolonise the justice system and provide real and long-lasting post-release opportunities through arts education? And how can a transgressive teaching model based on ‘illegal’ art and narratives – such as graffiti – work for those caught up in the legal system?

For one of us, being a child was about loving to make things; the more mess she made, the more ‘real’ her world became through paint, glitter, fabric and text. Now, as a parent, she realises she still likes learning through play and connecting with others. Her eldest daughter is ten years old – the minimum age for incarceration in the Northern Territory. It is hard to imagine that that fun-seeking child, still losing her baby teeth, could be legally incarcerated for a nonviolent crime. It stirs something in her mother’s own extant inner child – a longing to continue to make things in the world in an effort to change it.

When this researcher’s own sixteen-year relationship ended in 2018, she had to make a new life for herself and her children. She had a deep wanting to be creative and found herself spraying walls with Babes Paint Darwin, a group of diverse women teaching each other how to paint street art in Austin Lane. Her ex-husband was cynical about this new hobby – she was thirty-five years old – but it made complete sense to her soul. She wanted to make things; she wanted to make a new self and a new world that was hers, autonomously. The poetic paradox, however, was that by making her own new world, she was informing the worlds of other women around her, who were in turn impressing upon herself.

She carried these graffiti-informed realisations into the design and implementation of a carceral arts project in the Northern Territory, one centred on painting prisons walls.

AS A THEME for a creative art prison program, ‘graffiti’ might seem an odd choice, particularly when it is taught in an environment of surveillance. As Mark Halsey and Alison Young write, graffiti is

a paradoxical phenomenon – as both aesthetic practice and criminal activity. Its practitioners often vigorously assert its visual merit and its cultural value. Its detractors recommend its removal from urban streetscapes and the prosecution of graffiti writers.[iii]

Analysis of how a person learns to express themselves in prison through a transgressive art form – and how particular creative outputs point to the importance of improving personal wellbeing while incarcerated – is important. It also allows exploration of how a prison arts program can improve levels of motivation and future clarity as well as provide connections with the larger community in preparation for release.

Making a new identity and a new life is not easy, but it has purpose when we think about the larger part we play in the world. As Sarah Sentilles wrote in ‘Creation stories’, her 2021 essay for Griffith Review 73: Hey, Utopia!: ‘When we make art…we exercise the muscles we need to remake the world. We remember it’s possible to make something new.’[iv] To alter our own lives in fractions must require individual strength but, Sentilles wonders, what could be possible when we imagine together? Can a new world be made that has the capacity to hold all of us?

For a long time, graffiti’s cultural positioning between ‘art’ and ‘vandalism’ has been shifting. We now embrace the formerly derided art form with commissioned murals and celebrate street art through walking tours and street art festivals like the one that appears in Darwin every year. But graffiti, particularly in the ways we use it in the prison program, is about much more than paint on a wall. Several theories imply that using graffiti as a medium for expression might significantly enhance the motivation, progress and wellbeing of people who are incarcerated while also stemming recidivism.

If people feel uncertain about their identity[v] and unsure of the collectives they could belong to, they are also uncertain about which values, roles and norms they should embrace.[vi] This uncertainty often makes them worry about violating other people’s expectations – and anxious about being derided, criticised or rejected at any time.[vii] This often makes them sensitive to rejection or sees them experience similar problems, which can manifest as aggression or belligerence.[viii]

To address an uncertain sense of self, incarcerated people might express themselves creatively through poetry or painting. They could even sign their signature – an act known to increase the certainty individuals feel about their identity. But these behaviours don’t always provide resolution. In which case – and also in comparison with other artistic pursuits – graffiti is especially likely to clarify ideas of identity, diminish uncertainty and curb aggressive or unsuitable behaviour.

Graffiti artists are known to feel more certain about their identity after creating work; they become more receptive to other perspectives, activities and opportunities.[ix] They’re not as worried that these other behaviours will obscure their identity – an identity that is now stable and enduring. Their capacity to develop their skills, character and qualities improves and they feel able to modify their character and competence through what’s called a ‘growth mindset’.[x] If artists become more confident that they can fulfil their aspirations, this confidence promotes a state called ‘future clarity’, where the future feels more feasible, certain and vivid.[xi] People with this future clarity gravitate to more responsible behaviours[xii] and are more inclined to choose the courses of action that benefit their future over those that result in immediate pleasure.[xiii] They act more responsibly, diminishing the likelihood of irresponsible, illicit or inappropriate behaviours.

CALLS FOR A prison arts program in the Northern Territory came as an interventional response to the 2016 Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory. The Royal Commission’s final report explicitly states that the focus of time detainees spend in prison should be rehabilitation – and that case-management and exit planning, the banner under which education services fall, are ‘important to a child and young person’s prospects of rehabilitation and can reduce the risk of re-offending’.[xiv] Ywrite: A Prison Education Program for the Northern Territory was thus designed to support education that precedes rehabilitation and provides an alternative to the punitive responses of authorities.

The punitive measures enforced in Darwin’s Don Dale Youth Detention Centre prior to the Royal Commission included long periods of time in a small, concrete isolation cell. In 2016 images were aired on national television of one former detainee, Dylan Voller, inside the isolation cell, drawing attention to his safety and wellbeing as a child held in solitary confinement. Voller’s personal graffiti on the walls of cell BMU1 serve witness to his inhumane punishment. The signing of his name over and over again provides sociological and psychological evidence of his deteriorating state of mind and an urgency to be seen and to maintain a sense of self. Voller’s graffiti may be demonstrably illegal, but it has a far greater impact than that. Criminologists may reference graffiti within cultural criminology, but interviews with graffiti artists themselves show that in ‘contradistinction to their engaging in edgework, there is a kind of pleasure generated through the act of writing that is not exclusively bound to nor a function of transgression’.[xv]

Voller’s graffiti made literal an urgent need to locate a prison arts education program in the Northern Territory, gesturing towards the harsh reality of punitive measures typical of prison culture and the negative effects that punishment can have on a person’s wellbeing and the healthy mindset required for effective rehabilitation. Arguably, graffiti and art taught in prison also intersects with the need for carceral creative arts education to gauge the welfare of those incarcerated, offering intervention for those particularly at risk of depression, withdrawal, anxiety or even suicide.

In this way, commissioned graffiti practices may be a therapeutic activity that opens up further possibilities for self-actualisation and connection. If approximately four in five of those incarcerated in the Northern Territory identify as Aboriginal – and up to 70 per cent of those incarcerated reoffend within two years of being released from prison – it is imperative that a prison arts education program here be culturally appropriate and based on proven educational principles and outcomes for Indigenous learners.

THE AUSTRALIAN EDUCATION system has colonial roots. These roots run deep and can make it difficult for some Indigenous peoples to feel a sense of belonging and engagement in this system, which was not created with them in mind and requires them, in the words of University of South Australia researchers Anne Morrison, Lester-Irabinna Rigney, Robert Hattam and Abigail Diplock, to ‘leave their cultural assets at the school gate’.[xvi] Western and Indigenous knowledge systems are not necessarily opposing, but they do represent different ideas about knowledge, what should be learnt and how that learning should happen. Unfortunately, many Indigenous peoples do not have positive experiences with education in Australia. As Morrison et al. point out, continued deficit thinking ensures that ‘far too often Aboriginal peoples – rather than the education systems themselves – are framed as “the problem”’.[xvii]

Learning, however, is not a passive process of osmosis. Teachers play a very important role in whether learning occurs and to what degree students experience success. Teaching is an art, with the best teachers developing an intuitive understanding of what learners need to succeed.[xviii] This is, of course, an overgeneralisation: there are cultural aspects that also need to be considered to provide an optimal learning environment.[xix] Educational contexts can be optimised through the use of culturally appropriate teaching strategies, and learning can be delivered in a number of different ways depending on the learner’s needs. It is the teacher’s responsibility to know and decide how to do this.

Ywrite, which was designed for the Northern Territory, draws on aspects of the 8 Aboriginal Ways of Learning pedagogy, including story sharing, learning maps, non-verbal symbols and images, land links and community links. This approach embeds cultural understandings and encourages the use of Indigenous language; it also moves away from an individual focus to the idea of community achievement and relationality.[xx] [xxi]

Developed in 2018 by a team at Charles Darwin University, Ywrite involves working with Indigenous and non-Indigenous street artists to develop a concept design for murals within the women’s prison and to workshop activities that focus on building trust, self-esteem and the psychological preparedness for working together. The program also engages with social and political topics such as why people want to make things. How can we be the artists of our own lives? And how can we change the world by first changing ourselves?

In the program, creative writing activities begin by looking at the purpose of graffiti as activism all over the world. Students reflect on their own values, reasons for writing and artistic pursuits and create their own pseudonym and artist’s identity. It became clear from feedback that participants craved stimulating and fast-paced activities in contrast to the slow and monotonous cultural environment of the prison. One participant found there was ‘too much time to work on each activity. I get bored easily.’ Another noted the change to the usual routine: ‘It was good doing something fun and creative. It was not same old same old.’

Some participants shared the social issues they cared about and workshopped messages into three-word poems or six-word stories suitable for spray-painting on the wall. One participant expressed her autonomy with her three-word poems: ‘Here I am’ and ‘Here me out’. An Indigenous woman from Western Australia was known in the group for her impromptu rap each day in the yard and her passion for telling stories. She recalled that storytelling is ‘my favourite because it’s getting my story out there and getting my voice out there’.

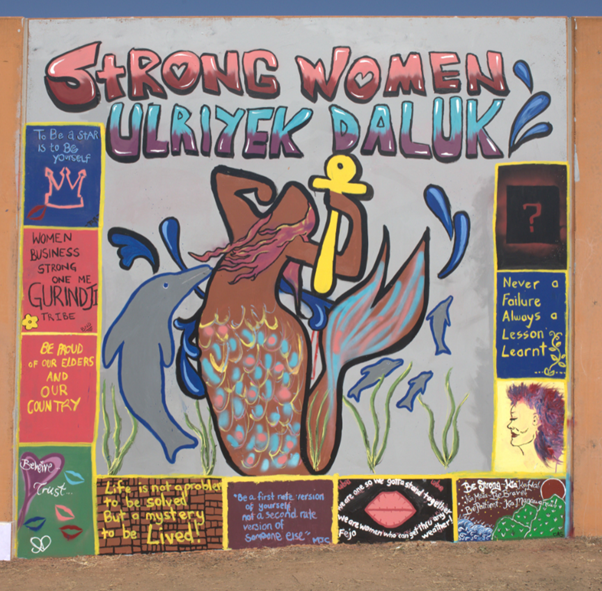

Given the restraints of publishing work from within prison, less traditional forms of getting stories ‘out there’ were explored, including the possibilities of painting pictures and messages as murals in the yard. This was agreed to on condition that the activity be completed for NAIDOC Week and the artwork be revealed at a formal morning tea with the women and staff. It was a unique and humanising opportunity for staff to mix with incarcerated women – several noted that this had never happened before. Women in the high-security section of the prison were also able to participate in the mural reveal and commented on the importance of being able to see its messages of hope from the cells where they lived twenty-three hours a day.

Mural painted with the assistance of Darwin artist Hannah Illingworth, a member of Babes Paint Darwin

WHEN YWRITE FIRST started, participants filled out a survey to gauge their mood, wellbeing and sense of future clarity. After completing the program, a follow-up survey indicated the participants felt better about themselves. They also seemed to feel they could shape their lives better: they felt they could both change the future and imagine it slightly more vividly. Furthermore, participants demonstrated a slightly higher level of growth mindset after the program; this represents a belief that they can change, a key determinant of resilience.

Understandably, tensions between the women and prison staff played a part in the mood and emotional stability of the women in the program. Permission from staff to paint certain images or take material into cells needed negotiating and slowed down artistic processes: one participant reported ‘really [wanting] to take back the sheets to my room. I drew my name in my book in my room and did shapes around my name.’ Participants were also required to understand and observe the Australian Government’s hierarchy of national and territory flags and to alter their original design – which assigned one flag to each corner of the mural – to respectfully include all flags at the top. (Since then, the Aboriginal flag has been made more freely available for more public use, characterising the possibility of equal representation and of it being held in the same regard as Australian and state flags.)

Mural painted with the assistance of Darwin artist Shilo McNamee, a member of Babes Paint Darwin

In 2020 the Darwin Street Art Festival funded the projection of murals painted in the women’s prison onto a tall city building as part of a community exhibition. Images and interviews were mashed to music and played consecutively over two days, displaying the women’s work – and their creative resilience – and reconnecting them to their community on the outside.

When asked about her resilience, one participant explained it not as ‘how many times I failed and got back up again’ but in terms of life being ‘a journey’: ‘our mistakes and heartbreaks are what gives us stepping stones to improve and better our journey in life.’

How did art make her feel?

‘I find art helps me to express my inner thoughts and create an outlet for positivity,’ she replied. ‘Art makes me feel free yet disciplined and how I want to be portrayed.’

And what did the program mean to her?

‘We are able to showcase our talents and skills which gives us a means to have a different outcome on our journey through life.’

Making things was less about filling in time and more a means to flex the necessary muscles for creating a new life.

Finally, we asked how important art and expression was to her.

‘Art is very important to me because it is an expression of my culture, my religion, my family, my prison community, my purpose in life and my country of Australia. It helps me to utilise my strength and beliefs to the extent of being one with these things, as well as providing an opportunity to reveal who I am.’

Mural painted with the assistance of Darwin artist Hannah Illingworth, a member of Babes Paint Darwin

ART IN PRISONS has been received in a variety of ways. In the late twentieth-century US penal system it was viewed at times with suspicion – even by participants – until arts programs were given a form of cultural legitimacy through the Black Arts Movement.[xxii] This peer approval helped participants determine if a program was ‘a tool of psychological warfare meant to “tame” them or a route to individual or collective liberation’.[xxiii] Some prisoners became respected in the Black Arts Movement for the insights of their creative works and their perseverance.

Prisons are constructs of power and control for social benefits, so any program approved by the system needs to show a positive outcome. Quantitative and qualitative research of the University of Denver Prison Arts Initiative has assisted in showing the benefits of arts programs, especially in the socio-emotional areas linked to better connection to community, achieving skills and belief in personal capacities.[xxiv] These extensive surveys and interview data conclude that arts programs can act ‘as counterspaces which promote resistance narratives and healing for incarcerated participants’ and build ‘social connections and relationships’.[xxv] Responses often focused on the relationship and empathy that external facilitators and educators brought into the situation.

In terms of the creative outcomes of projects in prisons, the epigraph for Razor Wire Women – a 2011 collection of essays and art by scholars, artists and activists both in and out of prison – quotes Vonda White, an incarcerated participant in the project:

I believe that the more we can have a voice, the more we can reach out to bring understanding to our situation, the more outside people are going to positively respond. Images and writing produced during the project do indeed open a window to the life and thoughts of the women who were in gaol at the time of the project. [xxvi]

The volume also notes that arts programs can provide opportunities to think critically about life in a creative way inside the power structure that participants are trapped within. Women who are incarcerated can share their voices and visions, adding to struggles for equality and justice for disenfranchised groups outside the prison system. And groups on the outside can promote the work of incarcerated people to challenge stereotypical perceptions of people in prison.[xxvii]

Projects in the Australian prison system vary from educational institutions offering art certificates and short-term grant projects through government bodies to religious groups seeking to improve outcomes for prisoners and their families. In the Northern Territory there has been an ongoing commitment to provide opportunities for inmates to practise and develop their art skills while in prison, with supported activities including training packages and, prior to the pandemic, public events through Darwin Festival where work is sold.[xxviii] An Australian Christian group has also promoted the benefits of creative outputs through the Art from Inside initiative, which supports prisoners to explore new talents and ultimately feel pride in having work in a gallery for viewing and purchase.[xxix]

LIKE ANY CONTRIBUTION to the education system, prison arts education is necessary for understanding what it means to be human in diverse and challenging cultural environments. Ywrite is a community program that explores how the artistic themes of graffiti and street art work to improve the wellbeing, mindset and sense of citizenship of those incarcerated and those at risk of returning to prison.

Graffiti – like life – is messy. But it is a transgressive form that can empower, create change and disrupt colonial environments. And yet, paradoxically, painting the prison demonstrates a respect for property rather than a willingness to destroy or vandalise it. It sits alongside the dualistic theme of freedom and discipline that came across in our interviews and appeared in participants’ artworks.

When asked what message of resilience she would like to see on the prison wall, one woman said, ‘Well, to me…I mean…we do fall back. But we are strong, right. So how about something like between balancing strong and bad thing together, ’cause we are in here for that, see. Read your poem,’ she said, turning to her friend. That friend then proudly took up her piece of paper to read:

We need women who are so strong they are gentle. So educated they can be humble. So fierce they can be compassionate. So passionate, they can be rational. And so disciplined they can be free.

All of this only underscores the continued need for prison arts education in the Northern Territory as part of Australia’s educational landscape – particularly alongside the 2021 Northern Territory Aboriginal Justice Agreement and its seven-year plan to reduce Indigenous incarceration.

As educators, social workers and prison staff, we are all given the opportunity to make things – not only in our own private and messy lives but also in the worlds we wish to live in and in the worlds where we work. By bringing beauty into dark places, we make new lives for ourselves and others. This is work, and it is art.

Authors’ note: The poetry, prose and artworks created within one Northern Territory prison are shared in this essay with permission of the program participants and the authorities from the correctional centre.

References

[i] UNICEF. (2017). Building the Future: Children and the Sustainable Development Goals in Rich Countries –Innocenti Report Card no. 14.www.unicef-irc.org/publications/890-building-the-future-children-and-the-sustainable-development-goals-in-rich-countries.html

[ii] Scott, B. (2011). Narrating the Law: A Poetics of Talmudic Legal Stories. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[iii] Halsey, M., & Young, A. (2006). ‘Our desires are ungovernable’: writing graffiti in urban space. Theoretical Criminology, 10(3), 275–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480606065908

[iv] Sentilles, S. (2021). Creation stories: The world-making power of art. Griffith Review 73: Hey, Utopia!. www.griffithreview.com/articles/creation-stories/

[v] Wicklund, R. A., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2013). Symbolic self-completion (e-book ed.). Routledge.

[vi] Kruglanski, A. W., Pierro, A., Mannetti, L., & De Grada, E. (2006). Groups as epistemic providers: Need for closure and the unfolding of group-centrism. Psychological Review, 113(1), 84–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.113.1.84

[vii] Barnett, M. D., Moore, J. M., & Harp, A. R. (2017). Who we are and how we feel: Self-discrepancy theory and specific affective states.Personality and Individual Differences, 111, 232–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.02.024

[viii] Kim, H., & Barry, C. T. (2021). The moderating effect of intolerance of uncertainty on the relation between narcissism and aggression. Current Psychology, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01542-9

[ix] Sherman, D. K., & Cohen, G. L. (2006). The psychology of self‐defense: Self‐affirmation theory. Advances in experimental social psychology, 38, 183–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38004-5

[x] Dweck, C. (2016, January 13). What having a “growth mindset” actually means. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/01/what-having-a-growth-mindset-actually-means

[xi]McElwee, R. O. B., & Haugh, J. A. (2010). Thinking clearly versus frequently about the future self: Exploring this distinction and its relation to possible selves. Self and Identity, 9(3), 298–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860903054290

[xii] Moss, S. A., Skinner, T. C., Alexi, N., & Wilson, S. G. (2018). Look into the crystal ball: Can vivid images of the future enhance physical health? Journal of Health Psychology, 23(13), 1689–1698. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316669582

[xiii] Moss, S. A., Ghafoori, E., & Smith, L. (2018). How to prevent unhelpful personality traits from evolving into unhelpful financial behaviors: The benefits of future clarity. Journal of Financial Therapy, 9(2), 2. https://doi.org/10.4148/1944-9771.1166

[xiv] Commonwealth of Australia. (2017). Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory Final Report, Volume 1. https://www.royalcommission.gov.au/child-detention/final-report

[xv] Halsey, M., & Young, A. (2006). ‘Our desires are ungovernable’: writing graffiti in urban space. Theoretical Criminology, 10(3), 275–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480606065908

[xvi] Morrison, A., Rigney, L. I., Hattam, R., & Diplock, A. (2019). Toward an Australian culturally responsive pedagogy: A narrative review of the literature. University of South Australia. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2019-08/apo-nid262951.pdf

[xvii] Morrison, A., Rigney, L. I., Hattam, R., & Diplock, A. (2019). Toward an Australian culturally responsive pedagogy: A narrative review of the literature. University of South Australia. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2019-08/apo-nid262951.pdf

[xviii] Hattie, J. A. C. (2003, October). Teachers make a difference: What is the research evidence? [Paper presentation]. Building teacher quality: What does the research tell us – ACER Research Conference, Melbourne, Australia. http://research.acer.edu.au/research_conference_2003/4/

[xix] Malin, M. (1994). What is a good teacher? Anglo and Aboriginal Australian views. Peabody Journal of Education, 69(2), 94–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/01619569409538767

[xx] Yunkaporta, T., & McGinty, S. (2009). Reclaiming Aboriginal knowledge at the cultural interface. The Australian Educational Researcher,36(2), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216899

[xxi] Martin, K., & Mirraboopa, B. (2003). Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for Indigenous and Indigenist re‐search, Journal of Australian Studies, 27(76), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050309387838

[xxii] Bernstein, L. (2010). America Is the Prison: Arts and Politics in Prison in the 1970s. University of North Carolina Press.

[xxiii] Bernstein, L. (2010). America Is the Prison: Arts and Politics in Prison in the 1970s. University of North Carolina Press.

[xxiv] Littman, D. M., & Sliva, S. M. (2021). “The walls came down”: A mixed-methods multi-site prison arts program evaluation. Justice Evaluation Journal, 2(4), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/24751979.2020.1853484

[xxv] Littman, D. M., & Sliva, S. M. (2021). “The walls came down”: A mixed-methods multi-site prison arts program evaluation. Justice Evaluation Journal, 2(4), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/24751979.2020.1853484

[xxvi] Lawston, J. M., & Lucas, A. E. (eds.). (2011). Razor Wire Women: Prisoners, Activist, Scholars, and Artists. State University of New York Press.

[xxvii] Lawston, J. M., & Lucas, A. E. (eds.). (2011). Razor Wire Women: Prisoners, Activist, Scholars, and Artists. State University of New York Press.

[xxviii] Lemke, L. (2016, August 19). Darwin Festival: Fannie Bay Gaol inmate art program offers creative pathways to healing, jobs. ABC News.https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-08-19/prisoner-artworks-on-display-at-darwin-festival/7768114

Share article

About the author

Adelle Sefton-Rowston

Dr Adelle Sefton-Rowston is the recipient of a Fulbright Scholarship to teach arts and writing in correctional centres in Alabama.

More from this edition

Real fobs

FictionListen to Winnie Dunn read her short story ‘Real fobs’. ONLY BOGANS AND dumb ethnics go to Western Sydney University. Real fobs won’t even bother. But I am...

Vestigial

FictionTHE BOY RAN past the house just as Sherwin held the clothes pegs up to the line. The sheet sprayed soapsuds on the sunken...

Dramatics

Fiction ANNIE DOESN’T RECOGNISE the old teacher at first glance, not consciously. She only registers a vague sense of disorientation that seems carried in by...