Featured in

- Published 20130604

- ISBN: 9781922079978

- Extent: 288 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

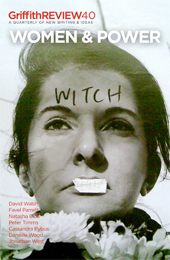

IT DID NOT take long before posters advertising performance artist Marina Abramovic’s show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art were defaced – literally. At the 23rd Street subway station ‘witch’ was scrawled on to Abramovic’s beautiful forehead, her lips stitched together with ink. Unlike the random graffiti often found in public places, this was an eloquent exposition, a marking pen dipped in the deep wells of subconscious fear of female power, used with the precision of a dagger.

Not that it worked. Over the three months of her performance, The Artist is Present, tens of thousands of people queued for hours to sit opposite Abramovic as she silently stared into their eyes (and souls), her power transcending words.

To call a woman a witch is one of the oldest forms of abuse, repeated the world over since ancient times, and with a surprising resonance in the modern world. In New York or Canberra it is likely to be limited to graffiti, placards and internet trolls and designed to undermine authority and legitimacy, but in the highlands of Papua New Guinea, or remote states of India, the mob is ready to kill ‘witches’.

LIAR is another word deeply embedded in the lexicon of male abuse of women, drawn no doubt from the mystery of female fertility and uncertainty, in the days before DNA testing, of paternity.

To see this language intruding into public discourse at the beginning of the twenty-first century is disturbing. Women may be better educated than ever and less dependent on men, even for procreation, but the dream of equality remains elusive, even in the most privileged societies.

The reaction to Sheryl Sandberg’s book, Lean In: Women, Work and the Will to Lead (Random House, 2013) has demonstrated the fear of female success, and the exercise of power by women, is not confined to men. Women have been leading the attack – blaming Sandberg for her success, her brains, her good fortune – rather than rising to the challenge she poses and the strategies she advocates to produce a more equal, harmonious and productive world.

The same week that Sandberg’s book was released to a confected media storm, one hundred and thirty-one countries agreed to a new United Nations convention that recognised as a human right that women should be able to live without violence.

The World Health Organization claims that 40 per cent of all women endure violence, and in many countries this rises to 70 per cent, much of it perpetrated by those closest to them. Sometimes this hits the headlines – like the recent, tip-of-the-iceberg, cases in India, South Africa and PNG – but more often it passes unremarked.

Like all such UN resolutions this was a compromise. But it was accepted by most nations, including those with a parlous disregard for women, and as a result provides a benchmark for the future. Many stepped away from the defence of last resort (culture) and agreed to ‘refrain from invoking any custom, traditions and religious considerations to avoid their obligations with respect to its [violence against women] elimination.’

Resolutions like this help bring female power and powerlessness into focus at a time when the dominant form of communication, horizontally, via the internet, is also undermining the power of traditional (male) gatekeepers. Like the telephone before it, the internet, at its best, enables women to communicate and mobilise in a new way. This is not without challenges, but the power of its horizontal person-to-person communication should not be underestimated. Disparaging this with dismissive language, such as ‘mummy bloggers’, deliberately misses the point of what Jeremy Rifkin describes as emerging in The Empathic Civilization (Viking, 2012). This civilisation, unlike the one we have grown up with, is driven by new insights from neuroscience and psychology and powered by the internet. Empathy is central, not a gender-specific trait, but a hard-wired and increasingly valued attribute, which will profoundly change the way power is exercised.

Not all women are generous, considerate or capable. Nor are all men. This is not a game in which if cats win, all dogs must die, but one in which the potential sum of the parts is much greater than the whole. Early in a transformative new century we need to hold our nerve, and transcend the ‘witch, liar, troll’ backlash.

18 March 2013

Share article

More from author

Move very fast and break many things

EssayWHEN FACEBOOK TURNED ten in 2014, Mark Zuckerberg, the founder and nerdish face of the social network, announced that its motto would cease to...

More from this edition

Amina’s lesson on contradiction

GR OnlineMY SISTER AMINA is the only Muslim lesbian I know. When I told her this, she said I was stereotyping both lesbians and Muslims,...

Do not bend

EssayTHEY ARRIVED BY mail the other day in an A4 envelope from the National Archives of Australia bearing a stamp that said: Do not...

Up-skirt

FictionA YOUNG WOMAN walks down the street towards an unremarkable terrace house wearing a fetching combination of op-shop style and nonchalance. Her upper lids...