Featured in

- Published 20130604

- ISBN: 9781922079978

- Extent: 288 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

AT THE END of what a friend described as the ‘worst week for women in living memory’, in August 2012 radio shock jock Alan Jones said that women, including Prime Minister Julia Gillard and Sydney mayor Clover Moore, were ‘destroying the joint’. The import of his statement was that women should not hold political power.

Subsequently, mainstream news and social media went into overdrive following Julia Gillard’s powerful naming and repudiation in Parliament, of sexism and misogyny. Watching it live at work, alone in my office, I almost stood and cheered. While her speech resonated globally, particularly with women, the largely male press gallery roundly criticised it. This seemed to miss the point. But that, of course, is the nature of hegemony.

In all of these reports and commentary, women feature as a construct, an unfamiliar being that simultaneously recalls my own experience of power and disempowerment and yet within an assemblage distant from my sense of self. I experienced recognition, yet no recognition. That is because in all these reports, particularly in the ‘analysis’ that followed Gillard’s speech, women were offered as the reflection of men and their own perceptions. We are not equipped to be leaders because of our interest in shoes, according to the former LNP Queensland State Secretary Michael O’Dwyer. We are women leaders or professional women doing a job; but are ‘precious’ old cows if we object to sexist name-calling, according to Grahame Morris, Liberal party strategist. The Anglican Diocese in Sydney ‘invites’ us to submit to men in marriage as part of a doctrine of male headship and as a corollary, the tragic death of Savita Halappanavar in Ireland and the spate of US legislative changes to limit contraception and abortion show that the law dominates our bodies. Still governing our bodies, parliamentarians across the world tell us that some rape is not real rape and that a single consent to sex is a lifetime pass (or at least a whole night’s pass) to consensual sex. In spite of this context, commentators and politicians accused Prime Minister Gillard of attacking the man not the ball when she named her – our – experience of misogyny and sexism.

Since the Prime Minister’s speech, women are visible and our experiences have currency. Finally women’s stories were silenced no longer because a woman in power called it. The response though indicates that there is a long way to go. This is so for a couple of reasons. The overwhelming representation of men in our culture and polity is supported by the erasure of women, our own accounts of life and our contribution to all realms of society. Feminist authors have long pointed out that historically both the narrative and intellectual characterisation of women’s experience has been interrupted by a number of strategies to silence us. These strategies continue, as evidenced by the current political debate in Australia.

This fact of life supports and is supported by an underlying social construction of women’s domain as the home. In the Western context, this has reflected a Victorian and capitalist utopia of the private home and hearth exposed by Betty Friedan in The Feminine Mystique. The Prime Minister’s speech was so powerful, because it described what women feel and what they know beyond that realm. In the broader context of feminist thought it justifies our self-determination and on an individual level, encourages us to break out of our externally limited, socially constructed mould.

Ongoing disbelief in the face of overwhelming evidence about how women experience the world – even in an affluent Western democracy such as Australia – represents a refusal to acknowledge where women are actually ‘located’ within society. Such widespread dissociation constitutes more than simply individual discrimination, warranting a closer look at our institutions to ascertain its derivation.

IN EXPLORING THIS disconnection, I consider the central role of power – patriarchal power – and control over women. While physical power, violence and emotional and psychological abuse remain serious issues I’m interested here in more subtle forms on a much wider scale. Patriarchal power and control occurs silently, without fanfare, through institutions and their structure, including legal institutions and the family. It is in this conceptualisation that the recent public discussion in Australia of misogyny and the ‘gender card’ became distracted, focussing on a personal hatred of individual women as key rather than the daily reproduction of significant structural inequality.

Regardless of the forum in which we are constructed by men – within religious or other public discourse, including by mainstream media and cultural representation – my legal background means that I cannot divorce what occurs in the public sphere from women’s broader treatment at the hands of the law. In governing and controlling women, the law parallels and reproduces structural disadvantage that exists elsewhere in society.

These parallels reflect the entrenched relationship between women, family and power.

Law represents power on so many different levels. It is manifest in the concept itself as the authority and enforceability of the will of the state. The institutions of the state likewise are instruments of law themselves – the courts, the parliament and the executive. Similarly, institutional office-holders have ostensible power by virtue of their office – including women such as the Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, and three of our sitting High Court judges: Susan Crennan, Susan Kiefel and Virginia Bell.

Indeed according to the Inter-Parliamentary Union Statement before the Third Committee of the UN General Assembly,'[a] key measure of women’s empowerment in society at large is their participation in politics.’ It might be suggested that the increasing list of women in positions of state institutional power in Australia signifies such general empowerment. However, in spite of remarkable achievements by our women political and legal leaders, I disagree that this necessarily means that women in general stand empowered. Holding office alone does not necessarily represent power in a broader sense, because the long history of silencing of women in the public sphere in particular has entrenched attitudes and modes of behaviour that erode women’s authority and therefore the power they wield.

In terms of political participation, Australian women can be considered to enjoy power in one sense. Non-Indigenous Australian women have had the right to vote in all jurisdictions since 1908, joined by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in 1962. Today, in spite of being 50.2 per cent of the Australian population, women’s overall level of representation in parliament is only 30 per cent. Women have the right to participate in the political process and institutions of governance, but the extent to which they hold power is vastly disproportional.

Based on evidence around the world, higher female parliamentary representation correlates with political processes including particular electoral systems, temporary measures such as quotas, and political opportunity. In systems lacking positive measures, including in Australia, there are practical barriers to women’s engagement in parliament. Despite removing legal impediments to women’s political participation, and assuming goodwill in pre-selecting women and a receptive electorate, the very structure and operation of the parliament itself closes the opportunity for many women who might otherwise participate. Sitting hours, lack of childcare and inability to bring children into parliament all presuppose a particular capacity for undertaking work as a parliamentarian, and thereby for taking institutional power. They also presuppose that women, not men, bear the responsibility to rear children.

Likewise, in the legal profession the ranks of senior lawyers from which the judiciary is selected, remain predominantly male. Twenty years of reports on the equality of women in the legal profession have seen a static proportion of women in senior positions – even now that there are 62 per cent women law graduates, and have been at least equal proportions of male/female graduates for a couple of decades.

In terms of ostensible power women qualify to hold institutional positions but there are other forces at work. These are cultural constructions of womanhood and underlying resistant influence and authority. These forces are the unwritten law, the lex non-scripta of public engagement and power historically developed and maintained by men. As these ‘rules’ have developed, they have reflected the experience of the men who invented them. They embody ideologies and norms that are now entrenched in social institutions and institutions of the law. Indeed these norms are so pervasive that we as individuals – men and women – have internalised them as our preferences.

As women increasingly take formal power, it is the expectations embodied in this other kind of power – the power of vested interests and internalised ideological assumptions – that are spilling out into public discourse. This has clear links to society’s conceptualisation of family, and what this imports in the context of women and their power.

FAMILY REMAINS THE implicit framework for thinking about women. It is shorthand for women’s capacity for procreation, our apparently innate capacity for nurturing, and indeed our very sexuality. A dangerous commodity, so we may infer.

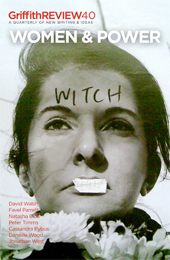

Gendered assumptions about women are formed and expressed in this context. So Prime Minister Gillard’s status as ‘deliberately barren’ is a means of classifying her in terms of family. Descriptions of her as a ‘witch’, a ‘bitch’ and a ‘cow’ all serve to reinforce her womanly status, being terms that relate particularly to her womanhood. Additional terms of rhetorical devaluation such as that she is ‘destroying the joint’ build on her gender as ostensibly unfit for office. Anne Summers has forensically analysed the sexualised commentary about the Prime Minister, concluding that in any other workplace such behaviours would clearly breach the Commonwealth Sex Discrimination Act. In focusing on the imagery and language surrounding depictions of the Prime Minister, Summers highlights the ideology generating it. This is the manifestation of traditional power and the way it is experienced and enacted by those who have made power what we expect it to be. The persistence and depth of sexist depictions of Julia Gillard, the Prime Minister, cause me to wonder whether the enactment of power embodied in the institution of Prime Minister is in fact destabilised when that Prime Minister is a woman.

I say this for two reasons. First, the traditional ostensible mode of power in political high office is a demonstrable authority accepted by and large throughout society. It is depicted as such through the media and other cultural representations. This person has power because of their status. Our previous prime ministers attracted critique, criticism, satire, parody and even hostility, but these men were not represented as leaders with no authority – and thus no power. Because we had never had a woman prime minister, the nexus between power and authority need never have been questioned. Now, having uncoupled the office of prime minister from men, the authority of the prime minister – regardless of her actual power and influence – is constantly under question.

Secondly, and following from this first proposition, it has been certainty of gender in these elected positions of power that has afforded gravitas to the office’s demonstrable authority. This underlying presumption about those in power supports the power as it appears on the surface. This suggests that it is not necessarily the office of prime minister that has been the source of influence in society, but the fact that it was a man who embodied the ideologies and norms of our patriarchal culture and who had risen within the patriarchal system. Instead of a person having power because of their status, perhaps the office embodies the power we ‘know’ to reside in a man. So completely have we internalised these norms, that we are unable to fathom why we reject the authority of the office of prime minister, now that a woman holds it.

Conversely, women are represented through the same values, norms and ideologies that associate men with power and authority – but that differentiate women from men in their capacity to lead and enact power through authority. Such values are widely owned through those with non-political power such as the church and the media, but also within circles of government. Marion Maddox argues that the ‘family values’ agenda of the Howard Government, presented as ‘pragmatic responses to economic or social pressures’, was instead ‘religiously motivated social engineering’. For example, the government implemented tax structures that favoured a stay-at-home mother, by implication not assisting women in the paid workforce, and through various means limited women’s reproductive rights.

In a more devolved sense, some consider women to have power within the family itself as its primary home-maker and child-rearer. In fact much feminist scholarship suggests that the family is as unjust for women as is the public sphere, being the heart and soul of creation and reproduction of gendered norms. In spite of this, such essentialist arguments persist and are so foundational to conceptions of how women behave, what is our appropriate sphere and in fact who we are, that they inform not just views on whether or how effective are women in ostensible power, but more insidiously inform the very law that governs us – both in public and in private.

‘WOMAN’ CONTINUES TO be a contentious legal subject. Even contemporary contract law textbooks continue to include a section about married women, highlighting the married woman’s common law status as a non-subject of law. The Married Women’s Property Acts in the late Nineteenth century finally recognised married women as autonomous; they ceased to be subsumed by their husband’s legal identity as a feme covert. The doctrine of coverture had recognised no property in the married woman apart from personal belongings, no right to enter into contracts and no right to sue. For the reason of her unified identity with her husband, nor could there be rape in marriage – a feature of Australian law until the 1980s.

The law’s construction of womanhood in fact begins at birth. The 2001 Family Court decision in Re Kevin, an application to change a man’s birth certificate thus enabling him to marry after gender reassignment surgery, highlights the power of the law over gender identity. Of course if marriage were not curtailed by its requirement of a man and a woman, such gender identity issues would not arise.

Caster Semenya’s experience at the hands – literally – of athletics officials around the world emphasises the contentious nature of legal womanhood in a different way. Semenya was required to prove again and again her identity as a woman, as officialdom challenged her gender status. At the 2012 Olympics, new testing was approved to determine womanhood. The testing was based on categorisations apparently not supported by scientific evidence, thus posing the question of what it really means to be a woman at all.

Postmodernists have taken this question seriously, suggesting that there is no ‘grand narrative’ of womanhood, and that such categorisations are limiting, failing as they do to reflect the complexity of experience and power. They have a point. However while I see differences related to class, culture, race, religious affiliation, sexuality and overall life circumstances, there is a lot to be gained by accepting, just for a moment, that womanhood can represent a shared experience. My own interest in observing life through the prism of the law certainly focuses on an idea of woman that helps me to interpret and analyse justice.

Within the text of the law, women’s experiences are constructions of law and therefore of power. These embody particular conceptualisations of what is woman and what is her function and they contribute to women’s disempowerment in a non-institutional sense – her power over herself. However, these underlying principles infect not just the private realm, but extend to the public sphere.

At law, women’s identity as mother and wife is so enmeshed within the fabric of the legal system that these foundation assumptions are invisible to those who proclaim them. Alan Jones was confused upon being asked if he was sexist. He responded that he has stood up for women and supported women into public office, even if he has not used words. Showing a similar lack of insight, Tony Abbott said recently that: ‘Never, never will I attempt to say that as a man, that I have been a victim of powerful forces beyond my control. And how dare any prime minister of Australia play the victim card.’Lawmakers too – both parliamentarians and judges – seem not to appreciate how the unwritten ‘law’ of ideology, assumptions about women and family, permeates the law they proclaim.

Suggestions of criminalisation of women engaging in altruistic surrogacy in Queensland, offers one example. On 21 June 2012, the Queensland Attorney-General, Jarrod Bleijie, announced that the government would legislate to disallow surrogacy for women who have been in a de facto relationship for less than two years, or who are lesbian. While this appears ostensibly to reflect a concern to protect children’s ‘right’ to a father and a mother, it ignores this apparently important right of children born lawfully into a variety of family structures. In fact, this is a question not of the rights of a child, but of the control of women who fall outside what the law sees as a ‘legitimate’ family relationship. ‘Legitimate’ in this case encompasses women who engage in ‘appropriate’ government-sanctioned sexual relations.

In another example, a 2012 case decided by the New South Wales Supreme Court, Madison Ashton claimed against the estate of millionaire Richard Pratt for breach of contract. She sued to enforce his promise to provide for her and her two children if she were available as his ‘mistress’ when he travelled to Sydney. Her claim failed including because the court found it was ‘meretricious’ – an arrangement to promote prostitution. The court need not even have considered this aspect of the arrangement, as it had already decided the case on the basis that it was a personal or domestic arrangement, and the law would not uphold a contract in the private sphere.

That domestic agreements have not traditionally been granted legal standing is a reflection of the deeply held liberal view of the home as a place outside the writ of the court. In this respect, the court, proclaiming contract law, exists for the public realm of commerce. Personal relationships are not appropriately subject to judicial scrutiny.

This raises two issues. The first is that in Ms Ashton’s case, the arrangement centred on remuneration. This was indeed in one sense a commercial arrangement, and the estate did not dispute this fact. Why then fall back on a traditional view that has slowly been unwound by the courts? The court then went to great pains to ensure that even if there were a contract, it would be void on other grounds as being immoral.

Secondly is the inconsistency inherent in these examples. Why should the law consider the relationship of Ms Ashton and Mr Pratt as beyond its authority due to its domestic nature, but on the other hand find it suitable to criminalise the behaviour of a lesbian altruistic surrogate, which would be lawful if she were heterosexual?

The answer to this illogic is that the law relies on strong underlying notions of women in terms of the broader concept of family in a way that disempowers. Once a woman encounters the law, the law will hold her to societal conceptions of ‘normal’ either through its sanction or its refusal to protect.

The law in one guise or another shapes our representation as women. This reflects contemporary yet dated views of womanhood and simultaneously reproduces and validates this construction. With limited public representations to the contrary and an effective and long-term silencing of women’s voices, experiences and self-identification, it is easy to dismiss women’s claims of sexism or misogyny. ‘Get over it. This is the world and you’ve just got to do a good job. The idea that you’d be shrill and whinging about this is just ridiculous’, was commentator Judith Sloan’s response to Julia Gillard’s misogyny speech.

That’s the way the world is? Yes, I agree that Sloan is right on this point. But in my view this must be challenged, rather than accepted. This is a matter of justice.

IDENTIFICATION OF WOMEN with family, through marital or parental status, or potential for marriage and motherhood, positions women firmly within the home and challenges their status if they embark into the public arena. For women who advance either within institutions of governance or in other public fields, their power is constrained by and large by their construction in terms of family. Contemporary debate about women’s equality, for example, is often framed in terms of availability and affordability of childcare. In spite of clear links between women’s engagement in paid work and the availability of childcare, this discussion tends to devolve into accusations of middle-class welfare rather than focusing on what prevents empowerment of women.

In contrast, the Howard Government provided financial support for stay-at-home mothers regardless of family income. Commentators such as Angela Shanahan wrote frequently in The Australian in support of this, again based on assumptions about what is right for families, what is right for women. She has argued consistently against downplaying women’s role as mother.

While women permeate the public consciousness in terms of their care of children, women who do not have children, and who may not even be partnered, are implicitly excluded from this discourse through their non-conformity with behavioural norms. Even ‘success’ in the public sphere fails to satisfy, for without fulfilling the predestined role for women in terms of family, we return to the question of whether these women are women at all. The responses to Prime Minister Gillard are evidence of this.

Despite the importance of affordable childcare to free women from their mothering role to engage in society outside the family, childcare need not be a women’s issue if women are not by default constructed as mothers. It is rather an issue of care for children. Mothering is indeed important. But it does not by default constitute women – childless or not. That these issues continue to centre on women and their motherhood status is telling of the profound ownership society has over women’s very being.

I do not see such debates about men as fathers, men as husbands. I do not see debates on men and childcare, men and parenting allowance or whether men should stay at home with children, father children, be prosecuted for fathering children, or are not real men because they do not have children. While certainly the construction of masculinity needs an open debate, and individual men are undoubtedly engaged in these issues at a personal level, in terms of power through institutional representation and the operation of the law, for a man, constraint of power through conflation with family is not in issue.

IN SPITE OF calls to the contrary, I hardly think that we should just ‘get on with it’; especially if ‘getting on with it’ means slipping back into the lazy positioning of women as wife, mother, daughter and sex object. We – men and women – should aspire to something more.

So long as women are perceived according to their place in a family structure their engagement as empowered citizens in political, legal, economic, social and cultural terms is limited. While women in their private lives may indeed experience and exercise power, as a structural issue this remains an inadequate framing of women’s experience.

As an alternative vision for women, we must return to a fundamental concept of dignity and self-determination. A de-coupling of woman from marriage and family is an essential part of this, opening the pathway for each girl, each woman, to map her own boundaries.

We must, as a society, adopt a more consciously critical approach to understanding how we represent women and how we unnecessarily tether women to their ‘biology’ through the very structure of our institutions. Following the lead of the Prime Minister, we must begin to name sexism and misogyny for what it is. This is not a ‘war’, it is not ‘divisive’, it is in fact restorative. For until we challenge the institutional elements of society to abandon womanhood as synonymous with family, we deny power through self-determination to over half the population.

Share article

About the author

Kate Galloway

A property lawyer for 16 years, in 2004 Kate Galloway joined the Law School at James Cook University where she teaches and researches in...

More from this edition

At that time in history

EssayYVONNE DE CARLO was a Canadian-born, American movie actor. The famous beauty was at the height of her film career in the 1940s and...

Liars, witches and trolls

EssayIT WAS SURPRISINGLY sunny the Sunday morning in October when we bumped into the PM. On a broken suburban footpath I nearly tripped over...

Amina’s lesson on contradiction

GR OnlineMY SISTER AMINA is the only Muslim lesbian I know. When I told her this, she said I was stereotyping both lesbians and Muslims,...