Ghost species and shadow places

Seabirds and plastic pollution on Lord Howe Island

Featured in

- Published 20190205

- ISBN: 9781925773408

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

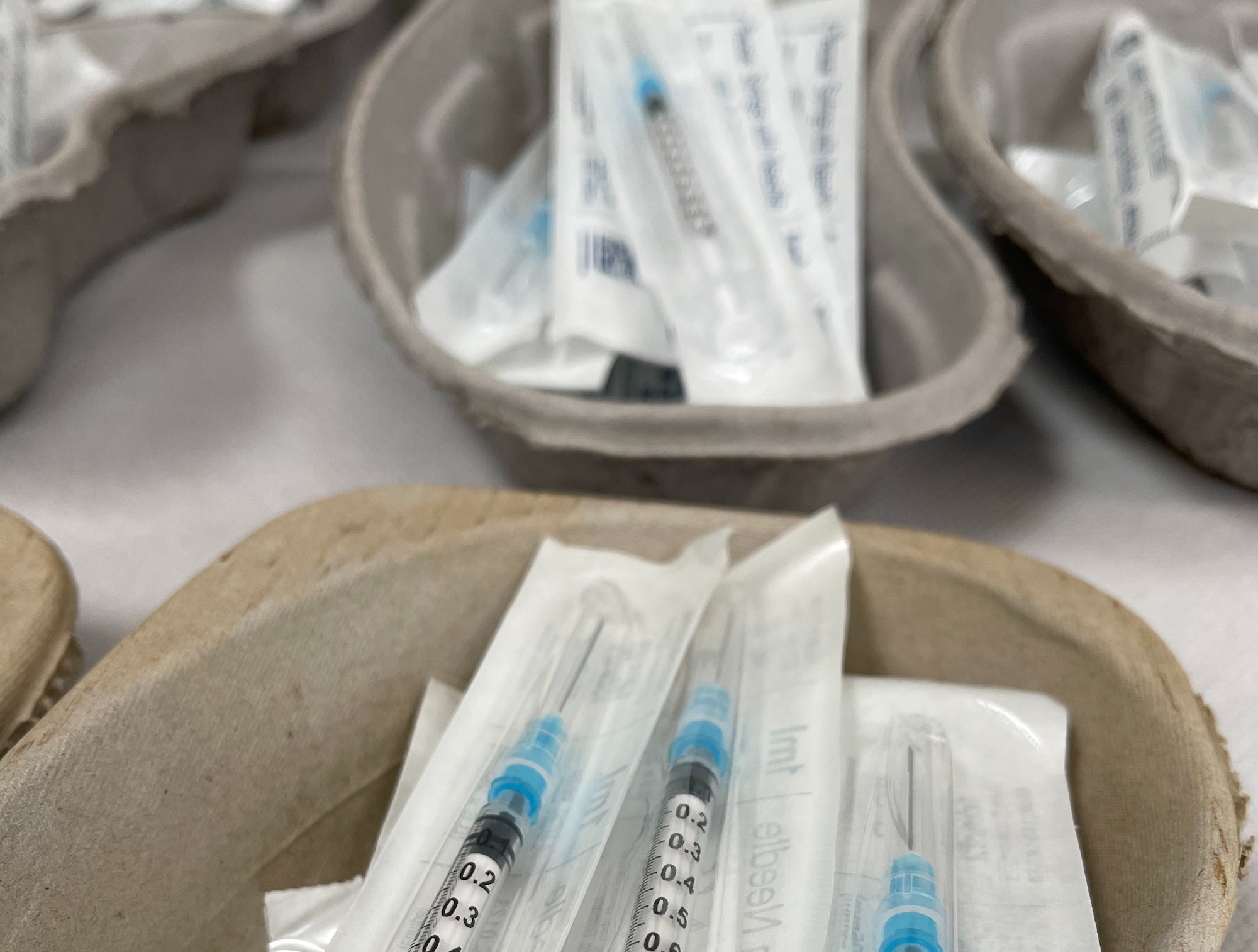

Weaponising privilege

ReportageEven then, ‘the strip’ was a parody of itself. But the Cross was still an idea, a state of mind. It was a place of organised crime, corrupt police, exploitation, inequality and violence – but it was also a place to find likeminded people, to escape judgment. Which is what makes the story of reform here so extraordinary – vulnerable people who gathered together to seek acceptance ended up working together for survival, liberation and change. Harm minimisation was shaped by a crisis that ultimately engendered credibility and resolve. From those beginnings, it continues to grow.

More from this edition

Eating turtle

ReportageONE NIGHT LATE in 2017, I knelt on a coral cay on the Great Barrier Reef, watching a green turtle lay eggs. It was...

On suicide watch?

IntroductionTHE WORLD IS full of beautiful places. Beaches and oceans, cliffs, forests, mountains and valleys, deserts, rivers, islands, harbours and bays. Places where the...

Crossing the line

EssayIMAGINE AN AIRPLANE flying north from Brisbane to Cairns. In just over two hours, it will cover nearly 1,400 kilometres of Australia’s eastern coastline and add 340 kilograms of carbon dioxide to each of its passengers’ personal carbon footprints.