Featured in

- Published 20250204

- ISBN: 978-1-923213-04-3

- Extent: 196 pp

- Paperback, ebook. PDF

…if I were asked to name the chief benefit of the house, I should say: the house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.

– Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

SOMETIMES, IF I can’t get to sleep, I imagine I’m back in the house where I grew up. (‘Grew up’ is probably a stretch – we lived there for nearly seven years, beginning when I was eight, but it was the longest we’d lived anywhere and when the time finally came, I found it hard to countenance the idea of leaving.) It was an old cottage on a hill in south-east England, and it had creaking floorboards, beamed ceilings and a long, unruly garden. There’d been a death upstairs the year before we moved in – one of the previous owners had had cancer and passed away in the master bedroom, surrounded by his family – but it was a peaceful house, and at well over a hundred years old must have witnessed more than one life reach its end. I like to go back there in my mind’s eye, conjuring the slightly crooked hallway, the doors that never neatly fit their frames, the tiny kitchen with its overwhelmingly wheaten spectrum of 1980s browns. Like handwriting on old foolscap, the more specific details have long faded with time, but the feeling remains: that ineffable sense of calm and familiarity that I associate with being home.

You likely know this feeling, too. If you’re lucky, like I am, it doesn’t only exist in recollection or imagination but in your present reality. Yet home can often be an uncertain prospect, whether because of dispossession, war, climate change, domestic violence, family discord, economic inequality…the list goes on. You may not associate it with a specific dwelling but with a person, a pet, a language, a landscape, a story, a song. But the idea of home is something we all have in common, even as the shape it takes transforms across time, place and experience.

NO PLACE LIKE Home traverses suburbs, cities and countries to reveal just some realisations of this idea. You’ll visit a tip shop, a Western Sydney pizza joint, a Midwestern American town, a London car park, a Cockatoo restaurant, the Manus Island detention centre, Wotjobaluk Country, Mer Island, a Denny’s, a post-apocalyptic world – and many more surprising and compelling locales. You’ll discover what’s really driving Australia’s property problem, how home can be wielded as a weapon of cultural destruction, why we’re haunted by the place we come from, what it means to be a third culture kid, how we hide secrets in our domestic interiors, how translation can tighten family ties, what it means to leave home and come back changed – and that’s by no means an exhaustive list of the stories in this collection.

This is a special edition in more ways than one. We’re delighted to have worked with two exceptional contributing editors, each of whom commissioned one essay in No Place Like Home: Samantha Faulkner worked with Jacinta Baragud on her piece ‘Mudth: My family, my home’, and Darby Jones worked with Barrina South on her piece ‘Follow the road to the yellow house: Seeking creative solace in the mountains’. Thank you, Sam and Darby, for your creativity, expertise and enthusiasm.

This edition also features the first two winning stories of our 2024 Emerging Voices competition: ‘The blue room’ by Myles McGuire and ‘Load’ by Lily Holloway. As always, a big thank you to Copyright Agency Cultural Fund for supporting this competition – we can’t wait to share these first two wonderful winning pieces with you (look out for the next three later in 2025). One of the many excellent shortlisted stories from 2024’s competition, ‘The pool’ by Tim Loveday, also features in these pages.

Finally, the release of No Place Like Home coincides with Griffith University’s fiftieth anniversary. The edition’s vibrant and topical mix of voices, perspectives and ideas is an apt reflection of Griffith’s pursuit of excellence and commitment to social justice. And, of course, Griffith University is the home of Griffith Review.

Wherever you are when you read this collection, whatever memories and associations and opinions its essays, stories, poems and conversations summon for you, I hope you find it a fitting tribute to the evergreen and enduring nature of home.

– November 2024

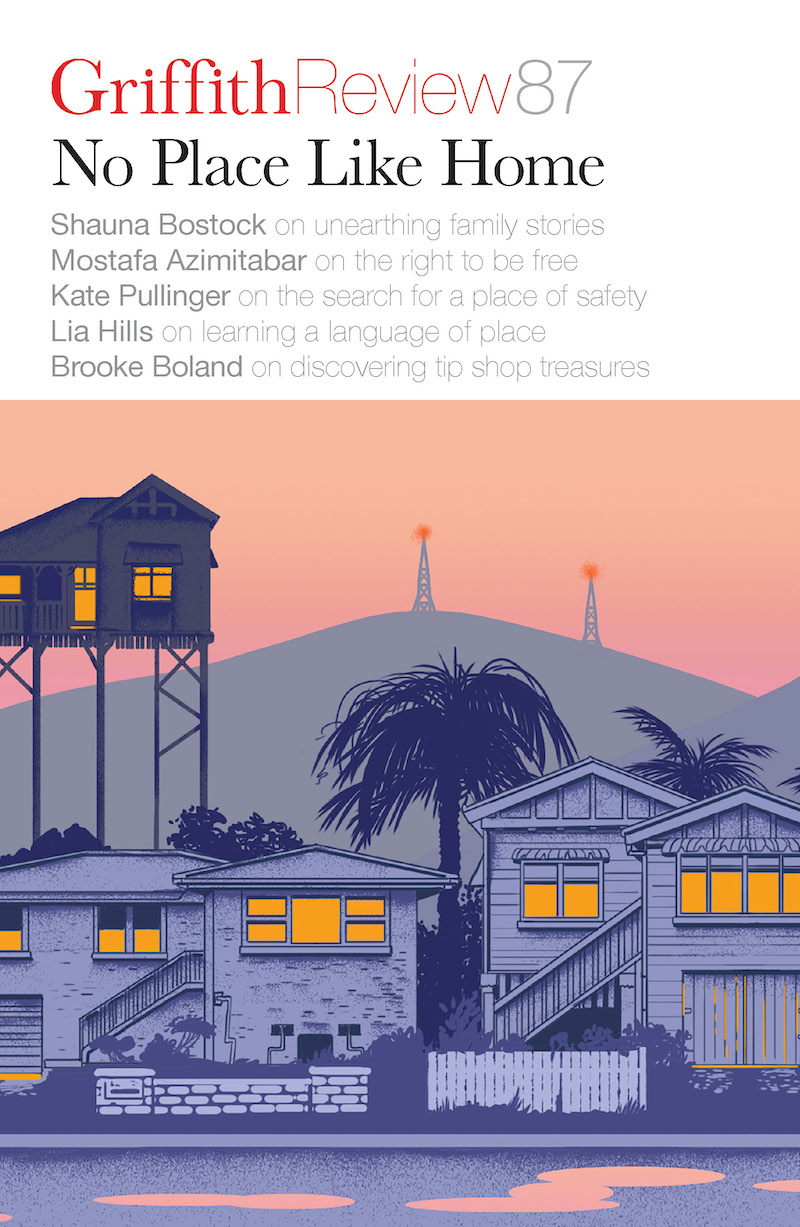

Image by Cristian Storto via Canva.com

Share article

More from author

Subject, object

The vivid hues and spiky leaves of Jason Moad’s Temple of Venus – the arresting artwork featured on the cover of Griffith Review 89: Here Be Monsters – raises a tantalisingly sinister proposition. The subject of the painting is clear – a Venus flytrap, realistically rendered – but there’s a somewhat otherworldly quality to this plant, a sense that it might be biding its time, waiting to strike while we, the viewers, are distracted by its beauty. For Melbourne-based realist painter Jason Moad, this slippage between subject and object, reality and imagination, is part of the point.

More from this edition

The blue room

FictionMum did not tell us that Sabina had tried to kill herself. She said that she was unwell, and because she was unmarried and her children lived interstate Sabina would stay with us while she convalesced. We figured it out after she arrived; she did not appear sick, but lively and plump. Nor was there any regularity to her medical appointments. Though Phoebe was irritated that she would have to share her bathroom we found the situation morbidly glamorous, the sick woman with the elegant name whose stay would end with recovery or its opposite. So many sibilant words: suicide, convalescence, Sabina. Having no knowledge of death or any conviction we would ever die, suicide seemed tinged with romance. That Sabina lived confirmed our belief that death was not serious.

Home is a long way away

Non-fictionThe Australian housing market is a wealth-generating machine, not a home-generating machine. So much is wrong with the current situation. No doubt you see it too; everybody seems to on some level. That’s why we keep hearing about the ‘Australian housing crisis’. I can see it, and I proudly consider myself an old-school capitalist, with a preference for free enterprise, fair competition, private property rights and the chance to make an occasional profit. We now find ourselves with a de facto caste system in Australia: the home owners relative to the home renters. Both groups need homes, but there is a marked wealth division between those collecting passive income on houses they own and those living solely on direct income who are forever chasing a rising market.

hearth

Poetry yes, one day, finally, it will all fall away like all dead things we will sit again by the campfire story illuminating the fall of empire one day again we...