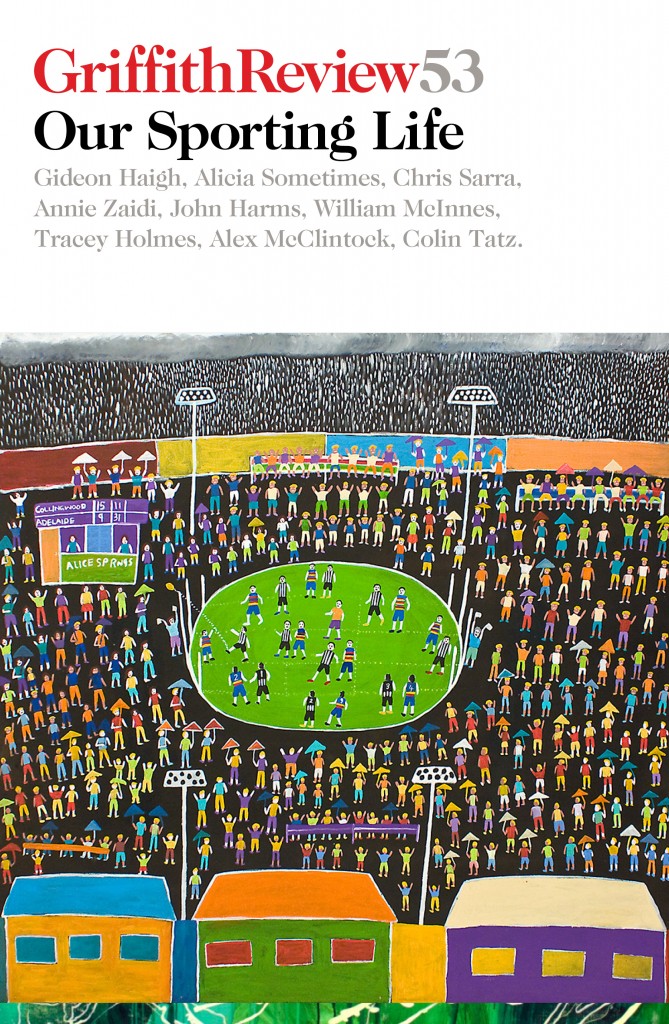

Featured in

- Published 20160802

- ISBN: 978-1-925355-53-6

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

A half-century of hatchet jobs

Non-fictionAuthors and publishers worry that bad reviews kill sales. I’ve seen no evidence that this is the case, but plenty that bad reviews distress and demoralise their subjects. Many people who care about literature endow criticism, and especially negative reviews, with magical powers. They hold dear the fantasy that if critics did a better job, if they were braver soldiers, the profound structural problems that bedevil Australian literature – books rushed to press, low pay, policy indifference, plummeting reading rates, crisis in higher education, not to mention the racism and the classism – might somehow disappear. A cracking review ennobles its subject with attention and consideration, but I’ve never seen one earn an author a higher advance on their next book or buy them more time for revision, let alone shift the federal arts budget.

More from this edition

Ferocious animals

FictionMY DAD WOKE me early to go down town and buy streamers. It was 1989 and our team was in the grand final for...

When the park comes alive

EssayTHERE’S A SPECIAL moment in mid-February when the grass at our local park is so smooth, tended so carefully, that it’s almost like a...

Time for spart: sport + art

EssayI LIVE AND work in the poorest electorate in the poorest state in the country, on the north-west coast of Tasmania. It may be...