Featured in

- Published 20220127

- ISBN: 978-1-92221-65-8

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Miriam Rose Ungunmerr Baumann is a renowned Aboriginal artist and educator. She was the first qualified Aboriginal teacher in the Northern Territory and, with others, established the Merrepen Arts Centre in Nauiyu (Daly River). She has also become widely known as the exponent of Dadirri, a spiritual practice of deep listening and still awareness. Miriam Rose is a member of the Ngangiwumirr language group and speaks five local languages as well as English. In 1998 she was made a Member of the Order of Australia for her services to art and education. She was the 2021 Senior Australian of the Year. Miriam Rose spoke to Kristina Olsson.

I WAS ONLY a tiny tot when I began my own formal education, living with my auntie and my uncle, a famous tracker. I went to school in Adelaide River, Pine Creek and Mataranka. Then when I was ten, I went back to Daly River to be with my mum. I went to Francis Xavier School then. And much later I went back as assistant teacher, teacher and principal. I really enjoyed going to school. Enjoyed being with my classmates, in the schools along the Stuart Highway, or at home. I was a good person to get on with. I gelled with everyone who was around me.

In our cultural way you’re being taught in two ways at the same time – you’re being taught in the Western way and you’re also being taught by your family. There’s always learning going on among our elders and our families. Trying to instil in us the things about who we are, where we belong, what language group – you know, which homeland. What are our dreamings, language…that sort of thing.

All that starts early. You go and ask a four-year-old or five-year-old there at home now, and they’ll tell you who they are.

When I’ve gone to your cities and towns to work, I’ve asked your kids: who are you? And they say, oh, I’m Mark Smith. So where does that come from, I ask them, the Smith name? And they’ve got to get on Google, they’ve got to get on the computer, on a website, to find out where the name Smith originated. That sort of thing. Whereas we, as Aboriginal people, we know who we are from the very early stages of our lives.

If you walked up to a four- or five-year-old in Daly River and asked them, who are you? – well, first they’d look at you really strangely because they don’t know you. And then, if you’re a teacher, they’d say: why are you asking me that question? You should know that. But they’ll answer you and say: I’m so-and-so, this is my Aboriginal name and I belong to that language group. They know who they are. Even at four or five.

In my own early education I learnt numeracy, literacy and all that, to get me up to a level where I could go off and study. And then go to uni. You have to meet certain standards to be accepted. And I did all of that, and then I went off and trained to be a teacher. Places like the institutes in Darwin, like Batchelor Institute where a lot of our local people trained, and Deakin University. At one stage Deakin was working jointly with Batchelor Institute. I got my degrees from them.

Before that we were at a boarding school set up by nuns from Our Lady of the Sacred Heart and the missions of the Sacred Heart. But our elders asked the church to come back to Nauiyu – Daly River – the community where I live now. To come back and do teaching and look after the elderly and help build the community.

The community also has a history with the Jesuits, back to the 1800s. Mary MacKillop’s brother was also there. Don MacKillop was in charge of the group there. They came from Seven Hills in South Australia. They left a legacy when they departed.

Then in the late 1940s or ’50s the elders said, we’ve got to get the missionaries back again. We’re going to ask the church mob in Darwin, you know, the Catholic Church, and they did send people out.

More recently people like the Jesuit Father Frank Brennan, he came out several times. Even now he keeps letting us know that he is with us in spirit, even if he is far away from us. But he’s been very close to the community, and he’s a friend of ours. He and Father Frank McCoy, they’re the ones who stand out when we’re talking about the Jesuits. There’s still a connection to them.

I can proudly say we were there when he was ordained in Brisbane, in Musgrave Park. The ceremony was out in the open. I designed the robe, the artwork on the vestment he wore, and his mum made it. The design replicated the design I’ve got on a lectern in our church at St Francis Xavier in Daly River.

BUT MY OWN teaching experience began way back, when a teacher of mine offered me the job of assistant in her classroom. And it all went from there. I liked it. I’d already dabbled in all sorts of things, when the nuns had different programs happening for us the year after we left school. To help us to understand what work meant.

There was the expectation you would work in the community or outside the community – so I got exposed to things and got involved in the clinic, the garden, cooking meals for the school boarders, or for the priests and the religious, nuns and brothers. Looking out for the kids in the dormitory, washing out the dormitory and cleaning up and doing the washing. That was work all right.

And then this teacher came along. At first she asked me to come and do some house cleaning for her, so I did that for a while. Then one day she saw me reading a paperback, and she said, I didn’t know you could read. Would you read me a paragraph, please? So I read her a paragraph and she said: right! You’re my assistant teacher from now on.

I was between sixteen and eighteen years old. And I really liked it.

Then she said she’d look for a place for me to go to and train. She was in contact with people in Darwin, and she organised for me to go off and start training there. That was the start of it. I got my teacher qualification.

At one time there I worked with art teachers in non-Indigenous schools in Victoria, in Carlton and Fitzroy and Camperdown. The kids didn’t know much about Aboriginal people, and that was good – I had them in the palm of my hand. They’d ask things like, where do didgeridoos come from? I’d say, where do you think, and they’d say: Woolworths.Then I’d explain to them that the men make the didgeridoos, and how and where, and they’d say, really?

I BELIEVE EDUCATION is a matter for the whole community. At the beginning, when I started teaching in my community, and teaching art, I was getting them to understand about our dances and all that. Some of the elders came to me and said, you shouldn’t be doing that, it’s not for the women to do that. It was new for them to accept me as a teacher in my own community, and teaching our kids art and dance. And I said, but it’s a creative way for children to understand the Dreamtime stories; it’s just what you taught me, and I’m passing it on. I’d spent a lot of time hanging out with my family and my elders when I was growing up and listening and understanding who I was and where I belonged.

And we don’t get that much time now with our kids because they spend all their days at school, so why shouldn’t I teach them the things the elders taught me? And in the Western way. So we did – we did all the cultural stuff and also taught them the Western way in maths and English and the other subjects. Eventually those elders understood.

It was important because I was the only one painting in my community. It was part of my assignments that I had to collect stories from the elders and then illustrate them and so on. I could draw and paint, and I taught everybody how to paint. And now they’ve taken the limelight from me, the young ones! I was doing it on purpose to get others to come up and stand on their own two feet, to start doing this. And we’ve got some really well-known artists in my community now and an arts centre called Merrepen Arts. We sell our artwork through there. And they do fabric painting too.

And art is part of the curriculum at school now. It’s a creative way of passing on the story instead of listening to somebody like me, or you, or someone, you know, talking, talking, talking. That’s boring, and kids start mucking around. But if you’ve given them a story, or tell them a story, and not just a Dreamtime story – it could be from their reader – and say: draw it, paint it. Get them to have a better understanding of what that story is, in their reader, or the Dreamtime story or true story or a sacred area.

It all keeps instilling in them the idea of belonging. All the children in our school have a relationship with elders. Everybody matters.

When I have the kids for culture, we take them out and we talk to them in language. And there is a sort of creole happening, a broken English, and the kids can communicate with you. Some are not very confident in talking to you in language, but if you talk to them they know what you’re saying. There are ten different language groups here.

It would be difficult to have a bilingual school. But we’re really, really trying to bring it back. We rely on the assistant teachers very heavily; every class has one or two assistant teachers, and they’re local, they’re a huge part of learning language. And we’re also looking more and more at how we use that in our early childhood classrooms in particular.

We’re going heavily down the path of oral language in the early years, oral language development in both languages, before we move to written language. Children who are strong and have a pride in their first language pick up a second language much more easily. And it’s the pride, being strong in culture, in language, and making sure we honour that. If you do that well, it helps with standard Australian English too, which they need to function in both worlds.

Even when I was studying, up to my master’s degree, there were challenges but not like now – fast cars, mobile phones, money, alcohol and drugs. Technology. I feel sorry for the young people because they’re the things they have to dodge to make the right choices. And the Sisters were always saying to us, when you’re grown and learnt things, you’ve also got to learn to walk in two worlds. There’s more and more pressure from the outside world, especially as you grow older.

Like being the first Aboriginal teacher aid, the first qualified teacher. I was only around nineteen or twenty, and it didn’t really throw me then – you think, what’s so special? But when you look back at it, yeah, it was very special. Now I’m an elder, and that’s where my other job starts, walking with the kids more than ever, that kind of thing. I still work with the children at school, but as well I’m making sure that whatever we’re trying to instil in our kids and young people about who they are, we have to make sure that happens. In dance and story, especially.

WHEN I STOPPED being principal of the school there was a lot of chopping and changing. Different people coming and going to be headmistress or headmaster. They’d only be there for a little while. But sometimes, with new people, they’d come in and throw out what we felt was a really good thing we had happening in the classroom as part of the curriculum. They’d come in with new ideas and throw things out and the school had to start all over again to work on what they’d brought. We had eight principals in seven years.

Kelly here (Kelly McGinlay) is the principal now, and as she says, how do you keep things on track when you’ve got eight different people coming in with eight different ideas? We have to look at the history, try to get back into what’s worked in the past, what already exists. And we have to bring the community along. It’s a community school, so we have to include community. It isn’t about some white person who comes in now and again. It’s about the local staff and those voices. That’s what’s important. It’s the voice of the community that makes it strong.

So I said, this has to stop. There’s got to be some stability. Otherwise it can be confusing. People get tired of all the changes. But Kelly, now, she’s made things straight down the line. It’s approved and part of the curriculum, all in black and white, all the things we’ve got to follow through with our kids.

IDEAS CHANGE ABOUT what a good education is, what a good education for Aboriginal kids is. It’s hard to keep up. There’s several systems throughout Australia, and I suppose a lot of families still make do with wherever they enrol their kids. They just hope they come out of it in a good way. And right now people throughout Australia are asking us, how do we work more closely with the First Australians?

And I wonder why they’re asking me that question. About how they can make things better for us, on our journey through life. And particularly with children you’ve got enrolled in your school. I say, well at least that’s a start. And from there you go to the family of that child, and ask them where their family is. Let them take you and introduce you to their family members, and invite them. Make the school inviting. Bring them to the school. We have a lot of things we celebrate throughout the year like NAIDOC, Harmony Day and so on. Open days. Start doing that and make the school welcoming and inviting for their families, because then you’ll have a better outcome with children you have enrolled in your school. Because they will know he or she isn’t the only one at your school – their families are part of it as well and part of their education.

I think the government is saying now that families are the first teacher. And why not continue in that way, both the educators and the families working with the kids as they’re being educated?

KIDS HERE STILL go away to boarding school. That’s hard sometimes because there’s not enough support for them there, they don’t get enough time spent with them. Some of them don’t understand what it’s all about in being there. And if they get into trouble, they give them one, two, three chances and they’re out the door. It’s sad because often no one even tries to sort out what the issues are. They’re gone. Packed up and sent on the plane back to their community. And they might have been away two or three years, and they’re lost. We’ve got to try to bring them back to reality again.

So if it doesn’t work, they come back and we try to do a lot of learning on country with them. And try to offer some pathways for children where boarding school just isn’t for them. We’ve got up to Year 10 at the school here now and we can keep children to Year 11 and 12 as well and offer things like functional literacy, functional numeracy and then some pathways programs. It’s early days but it’s definitely an alternative.

But families would still like lots of the children to succeed at boarding school. And there are success stories about kids who do really well, who go all the way through and finish. And they come back to community with lots of richness to offer. There are definitely lots of success stories.

THERE’S A LOT of budding artists in the school today. A lot of new ones coming up. I was the only artist for a long time; I suppose you could say I was the founder of the Arts Centre. Merrepen Arts. It’s very successful. But I’m leaving it to the young people now. I had to take time out from school to set it all up, and I got it going. Got the elders to come in and help. My mum was one of the artists there as well, along with others in the same age group as her, and it was fantastic. And now a lot of young ones coming up, and like I said, they’ve taken the limelight off me. It’s very successful, with all these budding artists in the school, and hopefully they will continue to develop their artistic way.

Some of my paintings are in the church here. St Francis Xavier. I painted the Stations of the Cross. The painting on the pulpit is the one that Father Brennan asked my permission to photograph. His mother then made a tapestry of it for his ordination vestments.

There are other lovely young artists doing a lot of artwork for special church celebrations. Like last weekend we had the bishop come and he did some baptisms, first communions and confirmations. And a lot of the assistants painted canvases and hung them around the church to express to the children what all that meant. You know, as in the ceremonies that they were going through at that time.

Art is a healing process as well. You know when you do artwork, it’s healing and the artists who do it are also growing in faith or Aboriginal spirituality – whether it’s a Christian biblical story or cultural Dreamtime story. It strengthens their whole being.

Westerners are better at recording things that they want to record and keep forever. Aboriginal people can express how they feel about a story, or what they believe, through art. And when you read a lot of the things that the anthropologists have found in the bush, there’s a lot of rock art and so on, and that was our way of recording things.

THE CONCEPT OF Dadirri has been around a long time. Of deep, silent listening, still awareness. It doesn’t really surprise me how big it has become, everywhere around the world. But I didn’t realise at the time that it would go in that way, that people around the world would connect with what I talk about. But it’s gone everywhere – even to Ireland! A singer there, Luka Bloom, from Tipperary. He’s written a song about it. And then people in America are also trying to learn what it’s all about and want to know more. In New Zealand too.

I used to have Dadirri tourists come to visit us, and the community would get involved. And we’d sit and talk and say, you just have to find time, even if it’s a half hour or an hour, just to sit quietly and find yourself. You know you can replenish your spirit – because you’re all bogged down with all sorts of things you do throughout the day. Your kids, your home, your family. So you need to have some time out, and when I say that some of them end up crying. And they say, how do I do that? It’s hard for a lot of people in the Western world.

So people from all over the country would come for this, even the schools from down south. Then, Covid came along.

But it’s all based in nature. We live in the bush, our community, and the bush is just there, the river’s just there, flowing past the community, and it’s lovely, we can connect with nature. It’s different here to say, Arnhem Land, it’s got the salt water and we’re by a big river, and it flows out to the oceans about three hours away. We’re river people. Famous for barramundi and crocodiles.

SO I STILL do a lot of that sort of thing, I’m still involved in community and in the school. People think I’m still the principal, but Kelly is. We still work together on things.

I’ve got a funny story to tell you, something that happened a little while ago. Kelly got a phone call one afternoon, they said they wanted to talk to the principal. And she said, yeah that’s me, Kelly. And they said, no, the principal, Miriam Rose. Kelly said, no, that’s me, I’m the principal – Miriam Rose used to be the principal.

So we sorted it out. Now I’m called the president. Kelly is the principal of our school, and I’m the president… We laugh at that. We’ve got some name badges coming and on mine that’s what it says: President.

Share article

About the author

Miriam Rose Ungunmerr Baumann

Miriam Rose Ungunmerr Baumann is a renowned Aboriginal artist and educator. She was the first fully qualified Aboriginal teacher in the Northern Territory. In...

More from this edition

High resolve

PoetrySo I taught myself to run again (again). It’s all about the playlist. Plus the way the cold forgives us, given time. I say good morning like...

University material

FictionJEFFREY AND MY mother were together for three years. I lived with them for their final year, when I was sixteen. Before that I...

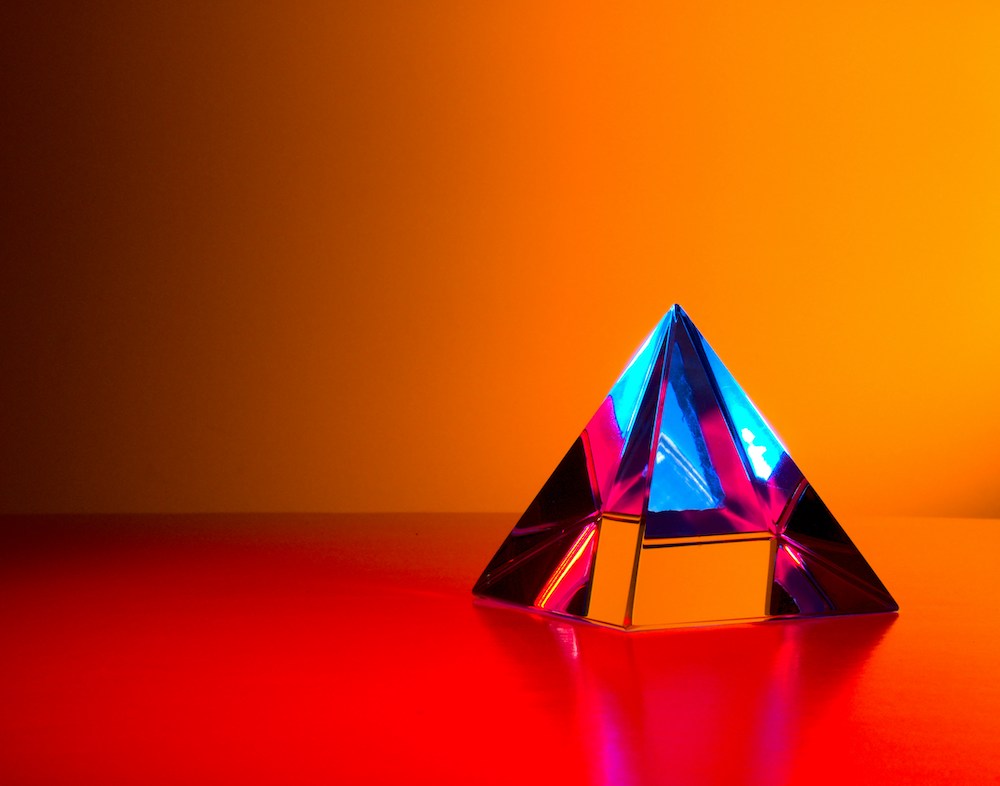

Prismatic perspectives

IntroductionClick here to listen to Editor Ashley Hay read her introduction ‘Prismatic perspectives’. IN 1816, DAVID Brewster, a Scottish mathematician and physicist, invented a new kind of optical device....