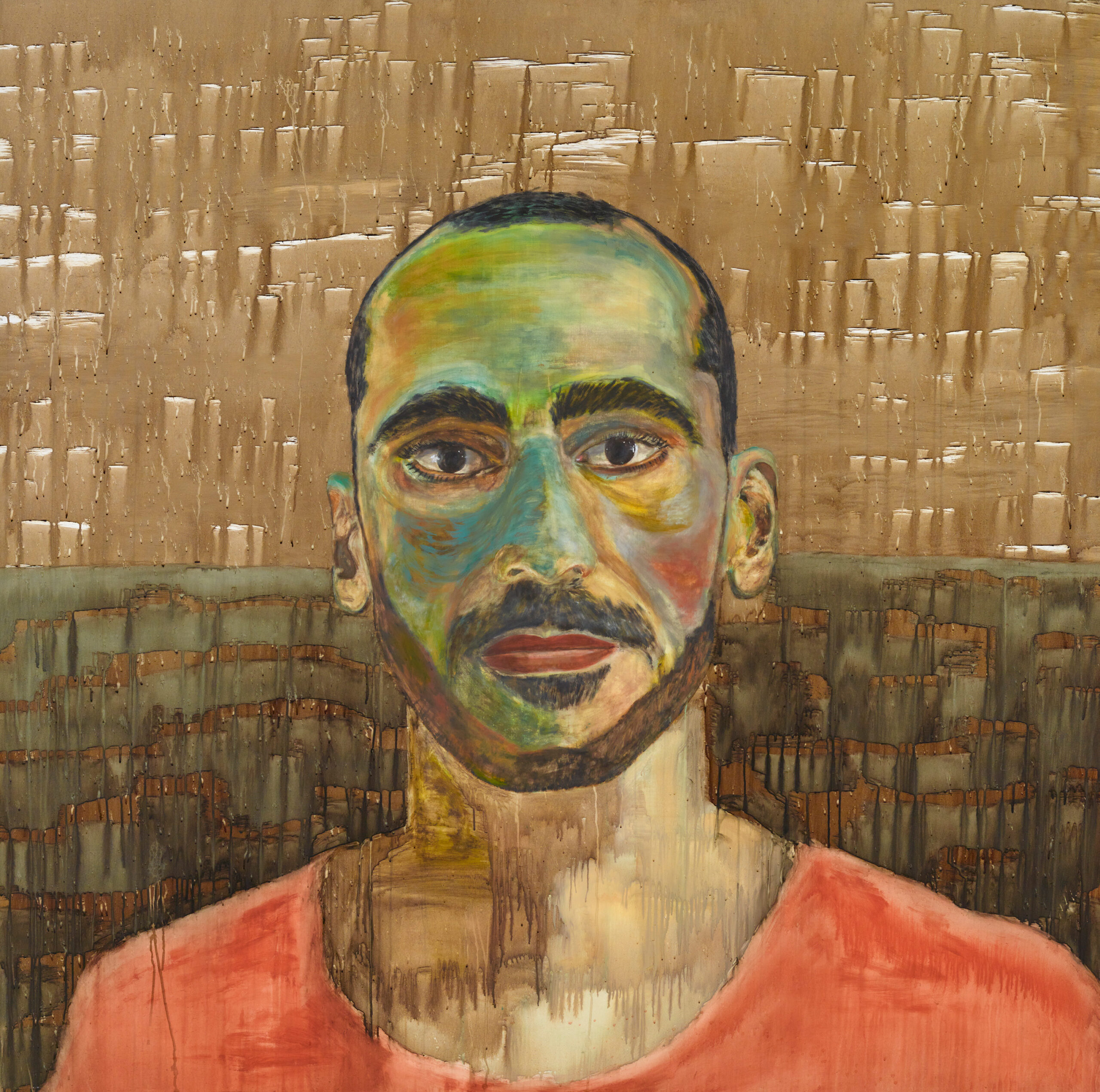

Painting behind bars

The art of fighting for freedom

Featured in

- Published 20250204

- ISBN: 978-1-923213-04-3

- Extent: 196 pp

- Paperback, ebook. PDF

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

About the author

Mostafa Azimitabar

Mostafa Azimitabar is a human-rights activist and two-time Archibald Prize finalist. As a refugee from Kurdistan, his status as an Australian resident is yet...

More from this edition

Mudth

Non-fictionMy family has its roots in several parts of the world: the Lui branch in New Caledonia, the Mosby branch in Virginia in the US, and the Baragud branch in Mabudawan village and Old Mawatta in the Western Province of PNG. Growing up, I spent most of my childhood with my Lui family at my family home, Kantok, on Iama Island. Kantok is a name we identify with as a family – it’s not a clan, it’s a dynasty. It carries important family beliefs and values, passed down from generation to generation. At Kantok, I learnt the true value and meaning of family: love, unity, respect and togetherness. My cousins were like my brothers and sisters – we had heaps of sleepovers and would go reef fishing together, play on the beach and walk out to the saiup (mud flats). I am reminded of these words spoken by an Elder in my family: ‘Teachings blor piknini [for children] must first come from within the four corners of your house.’

One language among many

Non-fiction Wyperfeld National Park, Wotjobaluk Country, October 2019 I PASS A defunct railway siding, the remnant mound like a sleeping animal. Pull up beside a mallee...

Steering upriver

Non-fictionAt dawn I cross the bridge, Missouri to Iowa, and turn down the gravel drive. Though I’m different now, this place is the same as it always is this time of year: the sun glowing red over the paddock next door, the grass not yet green, the maple stark. I go away, come back again, and home is like a photograph where time winds back, slows into stasis; where the carpet has changed, but the dishes have not, the cookbooks have not, the piano and artwork and bath towels have not. Here, I can be a child again, my best self, briefly. I hold on to this moment for as long as I can, because too soon I’ll remember how disobedient I am, how bossy and domineering, how I slammed my door until Dad took it off its hinges, how soap tastes in my mouth, how I pushed on these walls until they subsided.