Featured in

- Published 20250204

- ISBN: 978-1-923213-04-3

- Extent: 196 pp

- Paperback, ebook. PDF

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

Dying of exposure

Non-fictionPublishing is a weird industry, a retail supply service where every day hundreds – thousands – of brand-new, untested products are launched, each one a little bit different to the last. The long-haul career trajectory of most writers is increasingly difficult to maintain with incomes nosediving, as evidenced by multiple surveys. The road is cluttered with novelists brought down by ‘bad track’, their new books rejected because of the poor sales of previous titles. But as readers we still need help to discover good books, to figure out what to read next. As book pages, magazines and newspapers shrink or disappear altogether, it’s no longer clear what impact book reviewers can have on a career. The endorsement of someone whose work – critical or otherwise – you admire remains important to many writers.

More from this edition

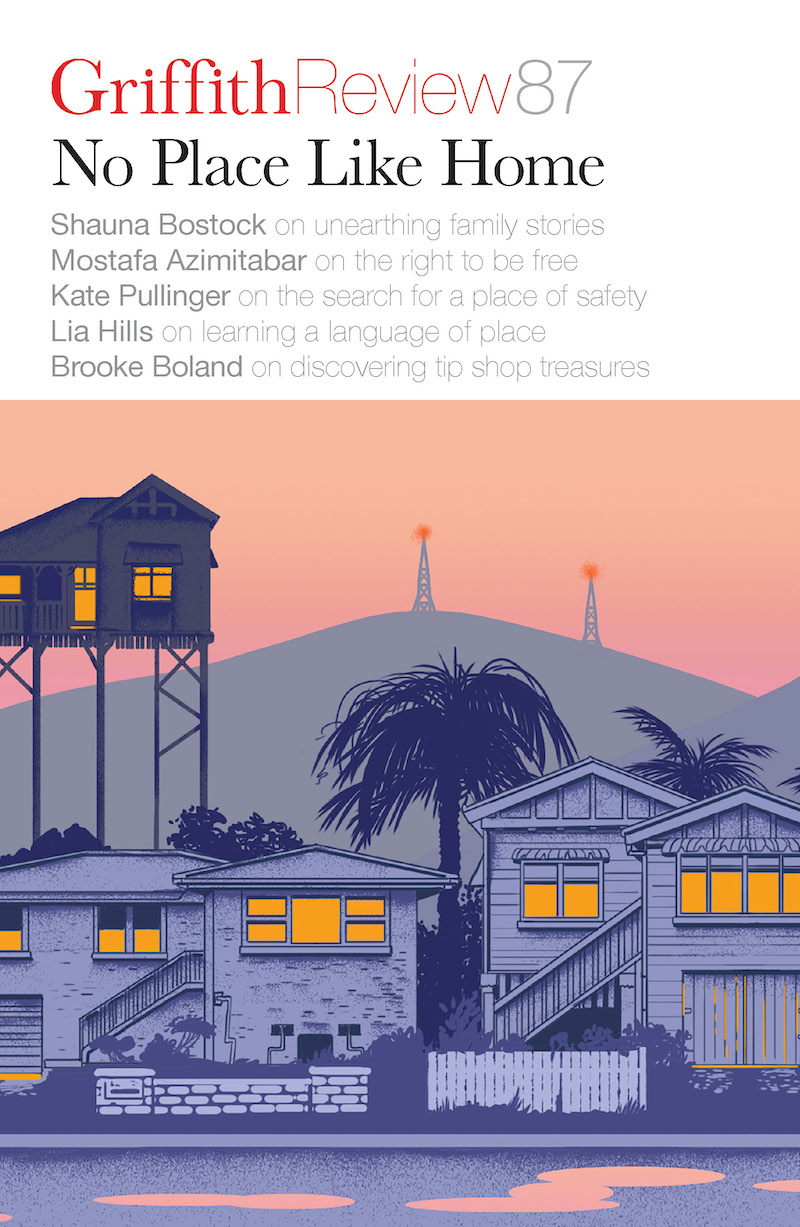

Safe as houses

IntroductionSometimes, if I can’t get to sleep, I imagine I’m back in the house where I grew up... I like to go back there in my mind’s eye, conjuring the slightly crooked hallway, the doors that never neatly fit their frames, the tiny kitchen with its overwhelmingly wheaten spectrum of 1980s browns. Like handwriting on old foolscap, the more specific details have long faded with time, but the feeling remains: that ineffable sense of calm and familiarity that I associate with being home.

Load

FictionWhen I wake up from being a dishwasher, curled on the floor of my apartment, it’s like I have woken from the perfect slumber. I don’t think I have felt like this since the womb. Imagine being able to temporarily kill yourself. The world, the body, weighs heavy. Being a dishwasher is the closest I have ever felt to bliss. Before this, the closest I got to bliss, true bliss, was getting high with my dad and eating a cream corn and cheddar toastie at the Murchison Tea Rooms.

Home is where the haunt is

Non-fiction I BELIEVE WE are all haunted by the place of our birth – which is chosen without our consent. Unlike a place of residence, which...