The network versus the hierarchy

New technology and the prophets of postcapitalism

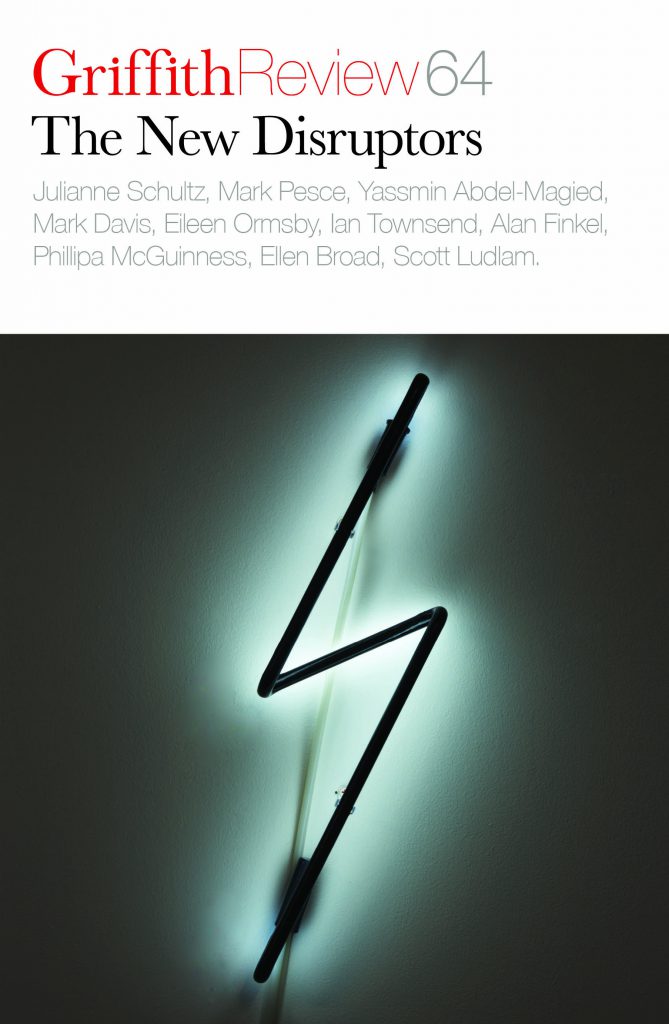

Featured in

- Published 20190507

- ISBN: 9781925773620

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

Nostalgia on demand

Non-fictionHow then do we approach a circumstance in which it is possible to consciously curate those memories and sense impressions, such that they become mere features of our ‘profile’? Or one where third parties, having gleaned enough data to know us better than we know ourselves, can supply those memories and impressions for us?

More from this edition

The search for ET

EssayOUR WORLD WAS made by a million geniuses. Just switching on a light invokes a chain of historical brilliance going back centuries: from the...

Seeing through the digital haze

IntroductionTHERE IS SOMETHING seductive about aircraft vapour trails, those long streaks – ice, carbon dioxide, soot and metal – that slice the sky. I’ve often...

Discounted goods

EssayWALK THROUGH THE doors of a suburban op shop and you’ll find the residue of household (de)composition that was once catalogued in rhyming newspaper-speak...