Featured in

- Published 20060606

- ISBN: 9780733318603

- Extent: 284 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm)

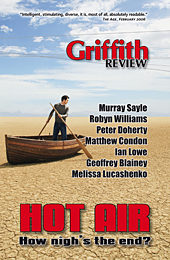

AFTER LISTENING TO the eminent scientist cataloguing the ever-increasing evidence of significant climate change – rising temperatures, rising seas, extreme weather, melting ice – and its potentially apocalyptic consequences, the reporter wanted to know how suddenly this would play out. “It’s always a question of what is sudden,” Professor John Schellnhuber replied. “The collapse of the western Antarctic icesheet may happen over centuries but in a geological time scale, this is very sudden.”

Therein lies one of the conundrums of the climate change debate. Sudden depends on how time is measured. For a scientist analysing changing concentrations of greenhouse gases captured over 650,000 years in a three-kilometre-long ice core, a twenty-seven per cent increase in carbon dioxide in a century is sudden, but for a politician locked into a three-year electoral cycle, sudden may be a jump in the polls from one week to the next. To a geologist, sudden may be a change that takes tens of thousands of years, yet play out over millennia for an archaeologist, take a century for a historian or a couple of seasons for a farmer.

In this movie-time world, defined by instant media, most of us expect sudden to be urgent, immediate and pressing. In the movies, a city can be inundated in the time it takes to eat a tub of popcorn; with half an eye on the television, a cyclone can form, denude a rainforest and flood a region between breakfast and dinner. This is the sort of time we have become accustomed to, but it is not particularly helpful in understanding either the causes or potential consequences of climate change. This will become apparent as you read this collection in which very different senses of time inform the perspectives presented.

What is known is that carbon dioxide is now accumulating in the atmosphere more rapidly than at any other time in recorded history and that the consequences of this are likely to be measured in significant changes, rising temperatures, melting ice, rising seas and extreme weather – both hot and cold – within this century. This is not a question of belief, as critics contend, but of evidence that can be tested and measured, drawing on the expertise of scientists from a dozen or more disciplines. They do not all agree, the competition between disciplines can lead to vigorous debates, but the trend line is clear and troubling as the rigorously peer-reviewed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has found.

The deep history of the planet shows that dramatic climate change has occurred in the past and will almost inevitably recur. What is new is the contention that as a result of profligate use of fossil fuels and an ever expanding population we are forcing temperatures to rise more suddenly. The complex questions the scientists have raised can no longer be addressed by science alone.

As befits an information age, more is now known about the world in which we live than could once have even been imagined. It is easy to get lost in the detail, to be uncertain about the science and confused by the rhetoric. It is therefore important to acknowledge that the institutionally conservative great national associations of scientists are united in their diagnosis that the evidence is pointing to dramatic changes in climate that are likely to affect the way we live in future. Most still hold out the hope that something can be done – by adopting renewable energy, modifying behaviour, limiting population growth, taxing unsustainable activities and developing new technologies – but increasing numbers of experts are adopting an even more pessimistic view: it may already be too late.

The sheer complexity of the data that is available about everything, from the air we breathe to the ground we walk on, is astonishing. More is known about the physical environment than has ever been known before. We know, for instance, that three plant or animal species are becoming extinct every hour while 9,000 more human babies are being born, and that the carboniferous age that laid down the great stores of fossil fuels 200 million years ago and that powers our world will never be repeated.

The citizens of previous great civilisations may have felt confident that they knew the limits of their world but this did not prevent their demise, as Jared Diamond has so compellingly documented in Collapse (Allen Lane, 2005). Changing weather patterns, drought, flood, fire, pestilence and war – the horsemen of the apocalypse – have played a part in the demise of many civilisations. The question is whether we are really such masters of the universe that we can prevent it happening again.

This challenging big-picture view of weather – as an adjunct and ally in the development of human civilisation – is often lost sight of in the daily deluge of new announcements, research, claims, counterclaims and the political posturing that passes for public debate about climate change. Putting global warming in this context provides a stimulating perspective. Much of the knowledge of the evolution of the planet and human life upon it has been acquired, tested and proven relatively recently. The very notion and capacity to measure the gases in the atmosphere, or trapped in the ice or in the remains of a human being tens of thousands of years old, is science that has evolved over less than a century – almost suddenly.

ALTHOUGH MORE IS now known, questions remain about whether that knowledge can be meaningfully applied in a way that draws from the lessons of history. If we were able to take and apply this knowledge to ensure the survival of the planet and civilisation as we know it, it would be an unprecedented feat of imagination and initiative. Such a project has never been attempted before; its portents are not good. Even if it succeeded, it could still be set to naught by natural systems beyond our control: tsunamis, volcanoes, asteroids and worse, as Murray Sayle notes in his remarkable essay, which ranges across time and space and traces the origins of our enduring fear of an apocalyptic end. He points to the problem that rests with our social and economic organisation, and notes that while the outcomes are unknowable, a solution of sorts may in part grow from sharper recognition that we all have only one earth, our home, Emoh Ruo.

Sayle finds in the rise and fall of the Dutch Republic – which in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries created a system of globalised capitalism and en passant discovered and named Tasmania – parallels to our time. It is ironic that the people of the Netherlands should provide this inspiration, as theirs is a country, with a quarter of the landmass below sea level, among the most vulnerable to the rising sea levels that are expected to accompany global climate change.

The long-term perspective that informs Sayle’s essay is both refreshing and challenging. It puts contemporary science into a historical and economic context in a way that has not been attempted before, and reveals with searing clarity the underlying problem, an issue occasionally referred to as the Cinderella of climate change. The quandary that goes to the heart of sustainable life on Earth is the sheer number of people living here: from one and half billion people a little more than a century ago, to six and a half billion human beings this month and nine billion in another fifty years. The exponential increase in global population and the resources that are required to sustain it continues even as the birthrate stalls in many developed countries.

The International Energy Agency predicted in 2004 that as a result of industrial and population growth the global demand for energy will increase by sixty percent by 2030. Eighty-five percent of that growth will be derived from fossil fuels, especially coal in China and India. Despite this enormous growth the IEA predicts that by 2030 the number of people with access to electricity will have fallen only slightly from 1.6 billion to 1.4 billion and 2.6 billion people will still be using traditional biomass for cooking and heating.

For a world with finite resources, and with an underlying, if periodically challenged, respect for human life, this presents almost unimaginable dilemmas and highlights the urgency and enormity of the problem. Many are confident that human ingenuity will solve the problem that by switching to renewable energy, by fostering the economic growth that means women have fewer babies, by learning to live in a sustainable way, life on Earth may continue to be viable. Others are less sanguine. Political leaders of all hues and geographic origin are declaring that global warming is the greatest challenge confronting the globe. Some even warn of a future beleaguered by wars over resources, with fighting not just over oil, but water, land, food – like something out of a dire, futuristic movie.

THE SERIOUSNESS WITH which climate change is being taken by the rest of the world comes as something of a shock to Australians, insulated as we are by land and distance and a political discourse that is sceptical about science but trusts technological solutions. The data that shows Australians are among the most profligate users of fossil fuels – as befits the world’s largest exporter of coal – is one of those abstractions that is easy to accept but hard to comprehend. Life in this country is not much touched by poisoned air and water, or the malodorous overcrowding typical in so many other places. Australians have always recognised the power of weather and the reality of climate change is beginning to gain popular currency, due in no small measure to news of extreme weather events, which may not themselves be a direct consequence of global warming, but contribute to a sense of foreboding. Droughts, El Niño, water shortages, shrinking snow, cyclones and searing temperatures remind us with increasing regularity that there are challenges in even this vast remote and ancient land.

For most, life is good, thanks in no small measure to the money generated from the sale of the prodigious quantities of fossil fuels and other resources that China needs for its industrialisation, and the ability to buy the cheap products manufactured in the plants fuelled by these resources – what the governor of the Reserve Bank called the China Factor. This takes the sting of urgency out of the debate here. Nothing is likely to happen suddenly, Australians are comfortable with complacency. Meanwhile many countries – including to a very limited degree even China and India – are wondering about they might continue to grow with less environmental impact. Australia’s wealth of fossil fuels neuters any will or incentive to capitalise on renewable energy for domestic use or global benefit.

Most Australians care deeply about the local environment – time and again it registers as the most pressing matter. Yet the consequences of global warming are likely to be profound, both personally and economically, at home and beyond. The CSIRO predicts that Australia will become more arid, that the average temperature is likely to rise by at least one to six degrees or more over the next sixty-five years, sea levels will rise, El Niño will become even more frequent, the Great Barrier Reef will continue to deteriorate, fierce fires will become commonplace and tropical cyclones more frequent and fiercer. Accompanying this will be habitat destruction and species extinction. The regional challenges will be even more serious.

It is possible that the economic and security consequences of global warming may force the issue onto the political agenda. As major insurance companies factor the costs of climate change and a market in trading carbon credits evolves, Australian business will be reluctant to miss out. There are plenty of advocates of the opportunities that could come from recognising the challenge and seeking to adapt to it. Even President Bush, his own wealth derived from oil, has cautioned his energy-hungry nation to seek to break its addiction to oil, but failed to propose any sanctions to achieve it.

Similarly, with more than a hundred million people living within a metre of mean sea level, many within this region, predicted rises in sea levels are likely to create another category of refugee – those fleeing environmentally unsustainable homelands. The future is likely to be volatile – the weather in one form or another may again determine our survival.

None of this is likely to happen suddenly in the popular understanding of the word, but the weight of evidence suggests that the march of climate change is well under way and this is the fleeting moment in which it must be addressed. It may be too late, the capacity for us to understand the information that is available and act wisely on it may be beyond our capacity for imagination, organisation and action – or the costs may be deemed too great and the benefits for as yet unborn generations too slight. But the burden and responsibility of knowing something is up rests heavily and uncomfortably on our shoulders.

Share article

More from author

Move very fast and break many things

EssayWHEN FACEBOOK TURNED ten in 2014, Mark Zuckerberg, the founder and nerdish face of the social network, announced that its motto would cease to...

More from this edition

The gang of six lost in Kyotoland

ReportageTHE ROTATING VAGARIES of diplomatic timetables decreed that the United States unveil its climate change trump card on the banks of the Mekong River....

Overloading Emoh Ruo: the rise and rise of hydrocarbon civilisation

EssayShortlisted, 2006 Queensland Premier’s Literary Awards, Science WritingShortlisted, 2006 Queensland Premier’s Literary Awards, Literary Work Advancing Public DebateShortlisted: 2006 Eureka Prize, Science JournalismNO ONE...

Flame bugs on the Sixth Island

FictionSelected for Best Australian Stories 2006 GO DOWN TO the rock pools when the evening tide is out and there is a chance you will...