Featured in

- Published 20170207

- ISBN: 9781925498295

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Hope is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul

And sings the tune without the words

And never stops at all

Emily Dickinson

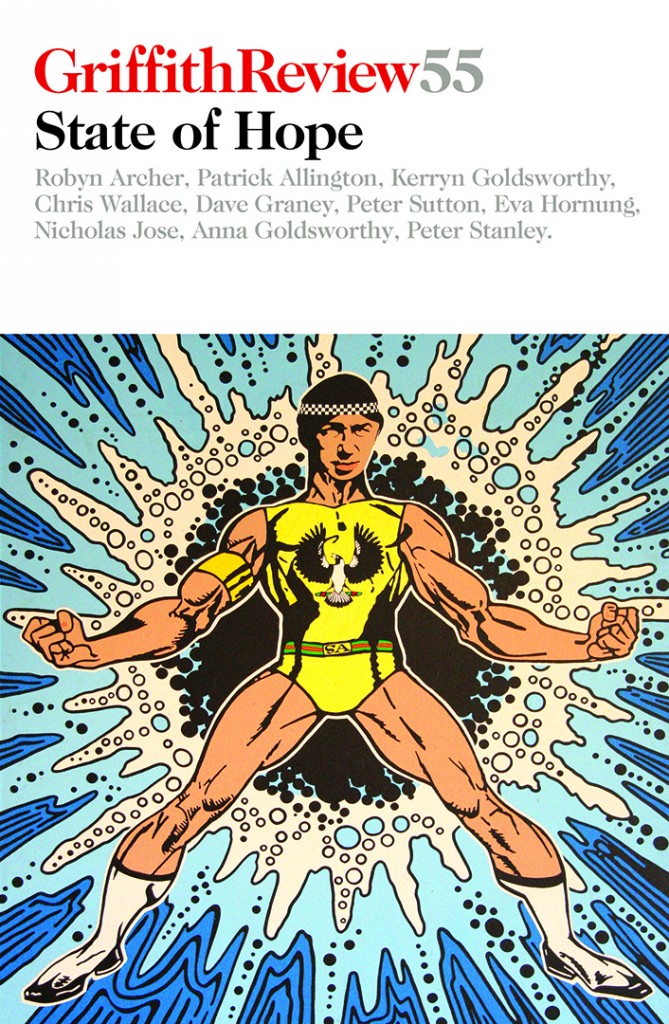

ADELAIDE IS AUSTRALIA’S only state capital city with a woman’s name. The others – Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Hobart and Perth – are named for great men of the British realm. Looking back, it seems perfect that the capital of South Australia is the odd one out. Adelaide, sitting in its central place in the continent, would be the first city in Australia – and one of the first in the Western world – where women could vote and stand for public office. One of the names its founders toyed with was ‘Felicia’, Latin for hope. Don Dunstan, Adelaide’s greatest reformer, would later use the name as the title of his memoirs.

Adelaide’s strength has always been the ideas, hard work and idealism of its people. As a young female student of Australian literature and history at Adelaide University in the 1970s I was nurtured, knowing South Australia’s feminist history, and I held hope that women were at last to achieve choice and equality in all matters. Suffragettes such as Mary Lee, Muriel Matters and Catherine Helen Spence were role models who proved that women could change things. They inspired our feminist values.

Of the three, Catherine Helen Spence was the woman who particularly sparked my admiration. She was a remarkable, independent woman who used wit and words to advance her causes. She was the first woman in Australia to stand for public office, the first to be published as an author and perhaps even the first woman journalist in Australia. Perhaps she inspired me to become a journalist when I left Adelaide University and joined the ABC newsroom. She wrote about women’s dependent status, the plight of children born out of marriage, their right to legal recognition and the inadequacy of divorce laws. Divorce law reform came first in in South Australia, but not until the 1970s! She was an early voice that laid foundations for the equality that women still champion today. Through her fiction, Spence championed reformist causes. As an eighteen year old I read her page-turner Clara Morison: A Tale of South Australia During the Gold Fever with its adventurous heroine who suffered all the challenges of being an independent young women in a colonial society that offered little regard or protection for women. As a writer and orator, Spence used the power of storytelling to advance the cause of reform in a range of social policy areas that were seen as radical at the time. She was a suffragette and feminist with a mission.

Mary Lee, perhaps Australia’s best known suffragette, was an Irish widow who arrived in Adelaide in 1879. By 1883 she was the founding secretary of the Social Purity Society’s ladies’ division and was campaigning to raise the age of consent to sixteen to improve conditions for women. The Social Purity Society soon recognised that women’s suffrage was essential to their aims and formed the Women’s Suffrage League in 1888 with Lee as the secretary. It was largely the combined efforts of Lee and her close friend Mary Colton, president of the Women’s Suffrage League from 1892, that suffrage was won in South Australia in 1894. A bust of Lee sits on North Terract, Adelaide’s main cultural boulevard, among a group of eminent men – the only woman in the group. Lee connected with other women suffragettes across the colonies. They were women writing to one another, across the distance of a vast country to inspire each another in seeking equality for women.

Celebrating the stories and contribution of women in my book Places Women Make (Wakefield Press, 2016), I listed these Australian pioneers of women’s rights as urban heroes:

Adelaide’s Catherine Helen Spence and later Mary Lee, Melbourne’s Vida Goldstein, Sydney’s Maybanke Anderson, and journalist-editor of The Dawn Lousia Lawson, Brisbane’s Emma Miller and Tasmania’s Jessie Spinks Rooke – despite the differences in the times in which they lived, their situations and class, [they] were kindred spirits. Through writing and publishing they created and continued a national movement aimed at improving the lives of women and their children in their communities. This desire to make an impact, to change attitudes or to make an idea a reality, really propelled them.

The story of Muriel Matters was recently given prominence in the film Suffragette (2015). She was an Adelaide-born suffragette who joined the Women’s Freedom League and made the cause public by chaining herself to an iron grille in the House of Commons in London. Through a legal technicality, she is said to have spoken the first words by a woman in the British Parliament. Frances Bedford, her descendent is fittingly deputy speaker of the South Australian Parliament today.

Douglas Pike’s Paradise of Dissent: South Australia 1829–57 (MUP, 1967), which is one of the best histories of colonial South Australia, tells of the early years of this independent colony that was never ruled by the colonial office. Many of the initial settlers of this ‘paradise of dissent’, the idea of which had been conceived in the imagination of British liberal theorists such as Wakefield and Gouger, had a passion for religious freedom, civil liberty and social opportunity. The idea of civic freedom and equality for everyone extended to listening to women and supporting their involvement in shaping society, and from the beginning single women immigrated to Adelaide to make their fortune. Many, like Spence, who came from Scotland, were looking for a chance, a husband and a better standard of living. Was it South Australia’s settlement pattern with women arriving independently as settlers, not as convict labour, that made it a state of female firsts?

Dame Roma Mitchell, who as governor lived on Adelaide’s cultural boulevard, North Terrace, was the first female governor of South Australia and of any Australian state. She set a path to be followed by many women in Australia, not just her hometown of Adelaide. Dame Roma, who balanced being truly part of Adelaide’s community life while holding its highest office, had the distinction of being the first woman to be chancellor of the University of Adelaide. She was also the first woman to be appointed to the Queen’s Counsel and, in 1965, was the first woman to become a Supreme Court judge. With Dame Roma Mitchell’s influence, much of Australia’s legislation for the protection of women’s rights in marriage and divorce, including rape in marriage and no-fault divorce, happened first in South Australia.

In many ways, the late Dame Mitchell was a woman who epitomised the Enlightenment thinking of South Australia. She took up causes she cared about, including nurturing a flourishing artistic life for Australia. She supported women in law and other professions, and, showing her love for the city, the heritage renewal of Adelaide’s North Terrace. The grand cultural boulevard, with the State Parliament and the Adelaide Festival Centre, was the street where she lived, and Dame Roma understood what it embodied for the people of South Australia. Places are more than bricks and mortar. It was a boulevard with very public aspirations: to meet the educational and cultural needs of the people of the then young, independent colony of South Australia. It still meets them today. Now, North Terrace is a street that represents the achievements of the city’s cultural life since settlement in 1836. It makes a connection to the past while embodying ideas, education, politics and change. It is the place Colonel William Light, the city’s planner, imagined. It is a place that looks to the future with hope.

North Terrace remains a place where Adelaide’s power games, plotting and decision-making occur. Dame Mitchell encouraged me to contribute to Adelaide’s public life as a young woman. When I served as an alderman on the Adelaide City Council, leading the contentious push to introduce policy to protect Adelaide’s precious colonial heritage, she once counseled me, ‘Don’t fret. Things work out.’ This wisdom has remained with me.

SOUTH AUSTRALIA WAS conceived as a utopian idea in the reformist fervour of the 1830s by a group of London liberals at the Reform Club. Edward Gibbon Wakefield, George Grote and William Molesworth met at this gentleman’s club in Pall Mall, which was formed by supporters of Britain’s Reform Act of 1832 and is still a gathering place to celebrate the birth of South Australia. These men, who are commemorated in street names in the city and north Adelaide, were driven by the idea of a free state that offered civil and religious liberty as well as economic opportunity for everyone, and removed the stigma from emigration. They shared ideals of systematic colonisation to create a more egalitarian and classless society, and worked on the South Australian project, conceiving the idea of a social utopia on the other side of the globe from their own country.

Wakefield and his work The Art of Colonisation influenced new thinking. As Pike writes of Wakefield in Paradise of Dissent:

He removed from emigration the stigma that had turned the middling classes against paupers, fugitives, poor relations and rum racketeers. He taught them to see instead solid opportunity and a civilising mission.

Wakefield never travelled to South Australia – in the end he was a colonist in New Zealand – yet his then radical ideas were behind the project that became South Australia and these reformist foundations make the place still different today.

OPEN STATE IS a current project of the South Australian state government that calls on community and experts to define the changes the state needs. Its launch coincided coincided with the 2016 Festival of Ideas’ call to action for South Australia: ‘Make or Break – doing nothing is not an option’. The Festival of Ideas first started in Adelaide in 2001 and is a weekend celebration of radical thinking. In 2016, founder Greg Mackie suggested South Australia could become ‘the thinking state’ – a place for thinkers to gather, work and plot the social reforms needed not just in South Australia but also nationally, even globally. It’s a big idea. More interesting to me, having left Adelaide fifteen years ago to live in Sydney, is the open intellectual preoccupation with defining a changing South Australia.

I grew up in the Adelaide of the 1960s and ’70s when Don Dunstan was a state premier who re-thought Adelaide’s place in the nation. I was twelve years old and Dunstan was the first Australian politician to make an impression. He awakened me to the idea that politics could change everyday life. The spirit of JFK and Jackie on the world stage is also an early political memory for me. These people would be called change agents today. Dunstan was elected in the mood for social change. He was a radical reformist at that time. As premier, he led social change in South Australia that other states looked to through the reform years of 1970–79.

In those same years the Liberal Movement led to the formation of the Australian Democrats, which became a force in national politics as an alternative to the two major parties. In South Australia, Steele Hall left the Liberal Party to form the more progressive Liberal Movement in 1972. The Liberal Movement later became the New Liberal Movement with Steele Hall elected as a federal senator.

The South Australian Liberal Party has been split between liberals and conservatives for as long as I can remember. In South Australia, local government was independent and not contested on party lines, and importantly remains that way.

Looking back, Don Dunstan was influential as a reformer beyond South Australia. He decriminalised homosexuality long before other states in the country. His administration saw the recognition of Aboriginal Lands Rights in SA, the abolition of the death penalty, the relaxation of censorship and drinking laws, improved legal rights for women, the introduction of heritage-protection law and the lowering of the voting age to eighteen, all of which were later followed in other states. Though a small city, Adelaide has been a breeding ground for people who want to influence national social policy. It was no surprise to me to see independent Senator Nick Xenophon and his team become a force in national politics in the recent 2016 election. The state is a breeding ground for independent thinking.

GROWING UP IN a place and at a time where social change was made and where feminism and women’s rights were part of history, I ran for public office in my early thirties in 1989 without being aware it might be unusual for a young woman to do so. As an independent candidate, I was only the eighth woman to be elected to the Adelaide City Council, the oldest local government in Australia.

When I was in public life in Adelaide as Deputy Lord Mayor in the early years of the 1990s, two influential South Australian senators, Natasha Stott Despoja and the late Janine Haines, were leaders of the Australian Democrats, who gained a significant federal vote of around 10 per cent. Both voices were heard in the national parliament. South Australian women politicians have taken the lead on the national stage and the list is impressive. Julia Gillard, our first woman prime minister, was educated at Unley High School. The first Liberal Party deputy prime minister and first female foreign minister Julie Bishop, former senator Amanda Vanstone and Senator Penny Wong were also all educated in Adelaide. Stott Despoja is still leading advocacy and action through Our Watch, which campaigns against violence to women, as she did in her former role as Australia’s commissioner for women and children. All these driven, committed and focused women are South Australians active beyond the state boundary. In the media, Fran Kelly of the ABC, Ann Summers and Helen McCabe are all Adelaide-educated women who have influenced public debate.

In Adelaide it is easy to connect because of the size of the city, and women in public life connected often. I used to see Stott Despoja in the supermarket, and I sat on the University of Adelaide council with Haines. Amanda Vanstone would be walking her dogs in the park, interested as any other local resident in the local heritage debate and other city council issues. In Adelaide, there is a sense of sisterhood among the women who serve or have served in public life. Despite political difference, there is a sense that as a woman you are part of a shared history of South Australian women contributing to make a difference.

THE HOPE FOR better times and for a better, fairer society for everybody was in the bloodstream of South Australia’s founders. In 1836, on the edge of desert country with nothing between West Beach and Antarctica except windswept yet ruggedly attractive Kangaroo Island, the directors of the South Australian Company set about planning a utopia. It began with the South Australian Foundation Act proclaimed by the British parliament in 1834. Researching for this piece, I found in my father’s library a centenary History of South Australia published in 1936 by the Royal Geographical Society of Australasia, a breakaway from London’s Royal Society. The chapter entitled ‘The Character of the Population’ opens with a quote from the 1838 emigration pamphlet ‘The Great South Land’:

We want no idlers, no drunkards; but steady, sober men not ashamed to live by the sweat of their brows will be welcomed, and cannot fail to become independent in a few years.

It was a pretty hopeful view of life and opportunity on the other side of the world in 1836. They didn’t mention women, but it is known that ships of women later arrived in Adelaide as colonists.

The whaling station at Kingscote on Kangaroo Island was one of the first commercial ventures in the state, and within a year of settlement in 1836 by June 1837 the first Adelaide issue of the South Australian Gazette and Colonial Register was printed. Adelaide was an experiment in government from the beginning: it involved commerce, profit from land ownership and freedom of the press. From the outset, things were done differently.Adelaide City Council, the first local government in Australia, was formed by October 1840, and South Australia became a self-governing state by 1851. The South Australia Company that founded the colony engaged Colonel William Light to plan the city, and sold land in the dormitory suburb of North Adelaide to willing colonists.

Growing up in Adelaide there were always Aboriginal people in the centre of the city and in the towns along the Murray, as well as working on the land in the outback. They had a place in the community. When I was at school, Adelaide appointed Australia’s first Indigenous state governor, Sir Doug Nicholls.

In colonial South Australia there was a treaty between the local Aboriginal people and the South Australia Company. Aboriginal people had the vote in SA before the time of Federation when it was taken away. The Wakefield Companion to South Australian History tells us:

The British government under Lord Melbourne containing some anti-slavery campaigners was now paying attention to the rights of indigenous peoples, including those in the proposed colony of South Australia. The colonial secretary, Lord Glenelg, wrote to the South Australian Colonisation Commissioners in July 1835 informing them that His Majesty had no intention of sanctioning ‘any act of injustice toward the aboriginal natives of that part of the Globe’ (cited in Law of the Land, p. 106). Efforts to have the Foundation Act amended to recognise prior Aboriginal ownership failed, but the Letters Patent issued prior to settlement promised to protect Aboriginal people in the ‘actual occupation and enjoyment’ of their land, the commissioners undertaking to negotiate for land and compensate those who ceded their land.

However, these undertakings were ignored until Governor George Gawler and Protector Matthew Moorhouse arrived in the colony in 1839. In 1840 Gawler upheld Aboriginal people’s proprietary and hereditary rights but refused to agree to land cession treaties, claiming that Aboriginal people would be disadvantaged by such negotiations. Instead, he argued that reserves of land should be held in trust until the Aboriginal peoples showed a willingness to use the land in a European manner.

Robert Gouger, one of the state’s founders, writes in South Australia in 1837:

So many miseries have been sustained by those unoffending creatures in different parts of the continent that I felt particularly anxious that the annals of our province should be unstained by native blood.

The Wakefield Companion to South Australian History has an interesting note on Aboriginal land rights giving the South Australian angle on the landmark 1992 Mabo decision:

The Pitjantjatjara Land Rights Act initiated by the Dunstan government was passed in 1981 in modified form by the Liberal government of David Tonkin, and the Maralinga-Tjarutja Land Rights Act was passed in 1984. None of these acts, however, constituted a recognition of native title, which came in 1992 with the High Court’s decision in Mabo. How far that recognition will go, and all that it entails, remain to be seen. The Mabo decision came about, in part, through a historical re‑examination of nineteenth-century British attitudes toward Indigenous rights to land, and arguments concerning Aboriginal rights to land in South Australia in the 1830s constituted an important part of that process.

The different history and profound influence of an enlightened South Australia on Australian law and social change is often not known by people in the eastern states of Australia.

ADELAIDIANS STILL HAVE today a great sense that their city is a fortunate place to live, and those who live elsewhere regularly make the treck back to maintain a deep connection to their special place in South Australia. I imagine this state pride and sense of being part of a unique community in Australia has always been so. People from Adelaide recognise the power and numbers of the eastern states, but are proud of the many things done well in South Australia.

Once Melbourne – bigger, richer and culturally connected – was the city Adelaide looked to. To an Adelaide schoolgirl such as myself, Melbourne had fashion and style. It exerted a pull as strong as football for the boys. Bringing up my children in the ’80s and ’90s in Adelaide, they still looked to Melbourne for a good time watching the football at the MCG or the Australian Open tennis. Sydney was away across the Hay Plains or the Great Dividing Range and not so much on the radar, but that all changed with the 2000 Olympics. Now most of my Adelaide friends have at least one child working in Sydney. This goes back to 1989 when the collapse of the State Bank of SA, and with it the state economy, made it necessary for a generation of bright kids to leave to pursue careers elsewhere. They left for Sydney, London, Hong Kong or New York. When the travellers returned to Australia, it was Sydney that offered the opportunities of a global city, as, to a lesser extent, did Melbourne. Yet Gen X and Millennials often return to revisit their roots in ‘Radelaide’, or continue to hang out with the ‘Radelaide’ diaspora in Sydney. Most South Australians still feel great pride in SA’s place in the creative life of the nation.

The arts were the one thing Adelaide never looked east for. Adelaide has the Adelaide Festival and does it well. South Australia has the popular Fringe Festival that follows the example of Edinburgh. South Australia created the Biennial of Australian Art, cheekily, in Adelaide, plus Adelaide Writers’ Week. In the early years, the authors (and many of the books) arrived from overseas. Local poets Geoffrey Dutton and Max Harris founded Sun Books in Adelaide in the 1960s to bolster the publishing of new writing in Australia. Quickly the Adelaide Writers’ Week was a magnet for Australian writers. Dunstan encouraged a flowering of the arts. The Adelaide Festival Centre was designed to be a crucible of contemporary artistic creation, as well as a showcase of the best in international art. Dunstan established the State Theatre Company with its own theatre to produce new works. He began the pioneering South Australian Film Corporation, which injected creative energy into filmmaking nationally.

This deep cultural life in South Australia goes all the way back to the plans of the founders who, in 1837, drew North Terrace as the city’s cultural boulevard. From the beginning, it was to have culture and opportunities to learn for all, with the university, the public art gallery, museum, library and Parliament House all neatly dotted along the terrace, planted with wide gardens and surrounded by parklands. This was years ahead of the garden city movement, a model method of urban planning initiated by Sir Ebenezer Howard in 1898 in the UK in an effort to foster healthier cities, with parks as the lungs of the city. Adelaide was blessed with the concept in Light’s plan from 1836. Garden cities were intended to be planned, self-contained communities surrounded by ‘greenbelts’, containing proportionate areas of residences, industry and agriculture. It was the inspiration for New York’s Central Park and is still relevant today in in informing the design of liveable cities.

Dunstan’s Adelaide Festival Centre was to be an addition to this cultural heritage. First suggested by a Lord Mayor and a Liberal government, it was delivered by Dunstan’s government and opened before the Sydney Opera House. It was then that Adelaide, with its arts centre alongside Parliament House, gained the nickname ‘The Athens of the South’. The Adelaide Festival Centre became the symbolic emblem of a city and state that had always had a rich cultural life at its heart.

Perhaps because of this many national leaders in all areas of the arts in Australia did some formative time in Adelaide. I first saw Cate Blanchett in the State Theatre of SA production of The Seagull. Some, like Rob Brookman, who ran the Sydney Theatre Company through a successful decade, and the current Adelaide Festival Director Rachel Healy, have returned while others, like Michael Lynch, Ron Radford and Mary Valentine, moved on. Adelaide has hosted many firsts in the arts, such as the bold Wagner Ring Cycle by the State Opera of South Australia.

Dunstan also looked to Asia for cultural exchange. He saw culinary change as a way to change the life of the city and, as a result, the state promoted the development of a cosmopolitan restaurant scene that embraced what was called ‘migrant culture’. This was epitomised by chef Cheong Liew, a pioneer of fusion food in Adelaide’s Hilton hotel who showed that the city was, as ever, hopeful and unafraid to try new things. Phillip Searle, with his famous chequerboard liquorice ice-cream, took restaurant food at that time to a new level, then moved on to Sydney.

SOUTH AUSTRALIA LOOKED outwards from the beginning. It exported copper, wheat and wool. The state was key to brokering the deal to reach agreement on Federation in a deal-breaker negotiation for East–West rail link to win agreement from Western Australia to join the Federation. In the 1950s, when Playford sought to build South Australia’s manufacturing base, it looked to other states to sell whitegoods and cars. The skilled labour force of the British weapons research facility in Salisbury laid the foundation for the growth of the defence industry capacity in South Australia.

John Bannon’s Labour leadership brought new international capability into Adelaide with the submarine building skills that would be needed beyond the state’s borders. He was first to embrace the big sports event as an economic stimulus with Australia’s first grand prix, an ’80s event that brought the glamour of the European racing teams and their groupies to the restaurant scene in they city. It was tourism as industry. The idea remains with Tour Down Under.

The Haigh’s Chocolates story epitomises the way South Australians look out to the world beyond Australian cities for knowledge and markets. Haigh’s Chocolates’ founder wrote to the well-established Swiss chocolate makers Lindt and Sprungli to ask for their recipe. They sent it and are said to have corresponded for years. Those from larger cities are surprised by the confidence of South Australians, who grow up in a remote city in world terms, yet engage globally. It has always been like this: never enough work or opportunity for people in South Australia so they drift elsewhere, taking their hope, optimism, ideas, products and belief that they have the talent to make a difference.

South Australians with a small local market have always had to think and be inventive to survive and succeed.

THE RECENT CITIZEN jury decision to turn down the idea of SA as a uranium waste depository shows the state’s sense of hope for something better is strong. It is a marker that the image as the creative state won’t sit with the reality of being a uranium dump. The deep thinkers know a hopeful future is in the land, with an artisan culture in food, farming and winemaking emerging as real opportunities. Tourism, even with the world’s most ancient landscape and pristine wilderness of the Flinders Rangers and the beaches of Kangaroo Island, is still relatively untapped. SA remains a leader in health education and services, the place Howard Florey, the discoverer of penicillin, could call home.

It is the state advanced in research to seek clean-energy solutions. High-quality primary, secondary and tertiary education and training remain part of South Australia’s strength. The secret will be to balancing these alternative economies with the uranium industry and the great Gawler Craton that sweeps across half the state with its contents still untapped.

Lord Mayor Martin Haese told me recently that Adelaide would soon have the fastest broadband in the nation, cheap inner-city rent and high quality of life, and will create wealth through this change while staying a mid-sized lifestyle city. However, employment remains challenging for South Australia. There are a million people living in poverty across Australia. In South Australia too many of its indigenous people are in this group. Unemployment and disadvantage is faced by a growing number of people in the state. All cities share this challenge of finding work for young people in a changing economy, where many jobs are now offshore. The ageing populations with little or no savings to support them are a national challenge. In Adelaide when I visit the mature age of the population is noticeable.

Adelaide, for better or for worse, has the most sophisticated defence industry in the country. It makes me wonder how can it use that skill to positive effect for the future? Can the technological skills acquired be adapted to more peaceful purposes? The French have won the latest shipbuilding contract in Adelaide and the creatives in town are looking for ways to weave their interest and investment into the cultural scene on the beautiful Fleurieu Peninsula.

The idea that anything is possible drives South Australia. Despite tough times in its economic and social history, the flame of the utopian society ‘Radelaide’ burns strongly. Apart from all the firsts in social legislation, the economy has always been based on innovation. The invention of the stump-jump plough, the hills hoist and optical lenses in light-safe plastic sunglasses were responses to local problems that were later marketed to across the world.

In a world where the only certainty is uncertainty, South Australia has the spirit to be inventive, to hope and to work hard. My bet is on the South Australian community rather than political leadership to build a better life for South Australians. That is where the real hope lies: in the strong sense of community in South Australia, the ability to look out to the world beyond and in its people.

Share article

About the author

Jane Jose

Jane Jose is the author of Places Women Make (Wakefield Press, 2015), which won the Australian Institute of Architects 2016 National Bates Smart Award for Architecture...

More from this edition

Bad breath

FictionRUMBA WONDERED WHY his parents were taking so long. He was both elated and anxious because he could keep drinking until he heard their...

The engine of Christmas

GR OnlineThen the Grinch thought of something he hadn’t before! Maybe Christmas, he thought, doesn’t come from a store. Dr Seuss, How the Grinch Stole Christmas! MAT...

A local footnote

FictionA WRITER HAS come to town. A reputation for greatness precedes him. His prize-winning books are plainly spoken, yet demanding. In person, he is...