Featured in

- Published 20161101

- ISBN: 9781925355543

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

THE AMERICAN WRITER on the festival circuit had refined his message into this decade’s preferred mode of communication: a list. He identified five points. Just as five is a useful number for a child using her fingers to learn to count, it is handy for the busy writer-slash-performer. His points demonstrated he’d reflected on his craft, but his thoughts could be distilled into one: if you want to be a writer, get on with it – or, in the jargon of another brand, just do it.

When reducing complexity to a list it is always good to have a strong positioning statement that restates the obvious, but in a way that cuts through and sounds fresh. Steve Hely, who has made his name writing for successful US television shows including 30 Rock and the Late Show with David Letterman, brought his undoubted talent to this task and said: ‘Only writing is writing. Talking about writing isn’t writing. Reading isn’t writing.’

It might be obvious, but it is also true and worth saying.

The cacophony of noise that surrounds successful writers – at events, in book clubs, on social media, in print, on air and in school and university classrooms – can weaken the art, make it seem mundane and ordinary, just words, and the author another celebrity who can be expected to have an opinion on anything.

IT CAN ALSO undermine the art of reading.

Reading, like writing, is a solitary activity. One you just have to get on and do by yourself. It can be shared, but only after the hard work of finding the time to sit down and focus on the words in front of you and actually enter the world the author has created.

The written word has never been more important, but we seem to be losing the art of reading, to access the deeper layers of meaning.

We are told that people check their smartphones about eighty-five times a day, which translates to more than five times an hour, assuming they detach while asleep. Almost all these checks require reading: texts, messages, tweets, posts, news grabs, story snippets – even video is subtitled.

At the same time, there is unprecedented attention on testing – measuring the levels of literacy from a young age with standard tests; periodic moral panics about the ability of graduates to spell or demonstrate understanding of grammar; and a low but insistent drumbeat that suggests the population is becoming less literate at the same time they are better educated than ever.

Reconciling these competing claims is not easy, but possibly points to the difference between knowing words and actually reading – extracting meaning, comprehending, going beyond the literal to the subtexts, interpreting words to enter another reality, and understanding how story, character and place can be created.

The effort to obscure meaning in political and managerial speech is well documented, as George Orwell wrote decades ago before the industry in obfuscation reached its current zenith: ‘Political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible,’ he famously declared in ‘Politics and the English Language’. They have also become less sophisticated and complex – as shown by the decline in the quality of debate in US presidential elections. The Princeton Review found that Lincoln’s debates in 1858, when literacy was far from universal, were at the level of a high-school senior, but a century later they slipped to tenth-grade level. By the year 2000, the two contenders were speaking like sixth graders, and now…

This lack of sophistication was clear when images of the abusive treatment of young people in the Northern Territory’s Don Dale Youth Detention Centre swamped the news for a few weeks mid year. The response from those close to the subject was to say, this had been known for ages: those with the interests of the young people at heart stated it accusingly; those charged with managing the system said it defensively. Even the Federal Minister for Indigenous Affairs Nigel Scullion conceded he must have read the official reports, but said the behaviour described was ‘not as easy to visualise as seeing the CCTV footage’.

At one level this speaks to the power of images, but at another it suggests that there are many people in positions of power who do not have the ability to really read. Not just see the words, but also work out what they actually mean, even if they are shrouded in jargon and designed to obscure. Reading requires the reader to slow down, take a leap into another world, adopt another perspective, turn words into images, quotes into conversation, exchanges into relationships in which power is unequally distributed. At best it can provide an opportunity to step aside and suspend reality – and then to bring an enriched understanding to making sense of the real world.

IN HIS CLEVER, bestselling novel Submission (William Heinemann, 2015) about an Islamic takeover of France in 2022, Michel Houellebecq explores the power and limits of the life of the mind and makes a passionate case for reading (and writing) literature:

Yet the special thing about literature, the major art form of a Western civilisation now ending before our very eyes, is not hard to define. Like literature, music can overwhelm you with sudden emotion, can move you to absolute sorrow or ecstasy; like literature, painting has the power to astonish, and to make you see the world through fresh eyes. But only literature can put you in touch with another human spirit, as a whole, with all its weaknesses and grandeurs, its limitations, its pettinesses, its obsessions, its beliefs; with whatever it finds moving, interesting, exciting repugnant. Only literature can give you access to a spirit from beyond the grave – a more direct, more complete, deeper access than you’d have in conversation with a friend. Even in our deepest, most lasting friendships we never speak as openly as when we face a blank page and address a reader we do not know.

This essential power of literature has been undermined by the pressures of the age: too little time to reflect, too much mediocrity hyped beyond its worth. As a consequence, the art form best able to evoke empathy – the sentiment most needed yet in shortest supply at this time – has lost its standing as the major, foundational art form.

Not everyone can write well, but everyone can learn to read well. Robert Dessaix has been captivating festival audiences who grew up reading Enid Blyton’s Famous Five novels – flawed, prissy, gendered books that nonetheless established a visceral imaginative framework for a generation of children growing up in the colonies, just as JK Rowlings’ Harry Potter did for their children and Andy Griffiths’ Treehouse sagas are doing for their grandchildren.

At the Sydney Story Factory, children learn the power of telling, writing and reading. When asked what makes a good story, the most conscientious eight-year-olds are quick to say, ‘Orientation, conflict, resolution.’ It takes the tutors some time to unpick this to get them to engage with the power of language, story, character and adventure, rather than the jargon of curricula.

The power of story should not be underestimated.

Although the must-read books of the year nominated by important public figures rarely include novels, they should. Submission and another award-winning French novel, Arab Jazz (Quercus, 2015) by Karim Miské, provide more insight into the dilemmas facing France than countless reports; Atticus Lish’s remarkable Preparation for the Next Life (Tyrant Books, 2014) takes the reader deep into the America that has enabled Donald Trump to flower; AS Patric’s Miles Franklin-winning Black Rock White City (Transit Lounge, 2015) explores the lived reality of refugees making a new life in suburban Australia with sophistication and flair. All these books provide something more vivid than CCTV images – they actually transport the careful reader into the heads of the characters and the situations they face.

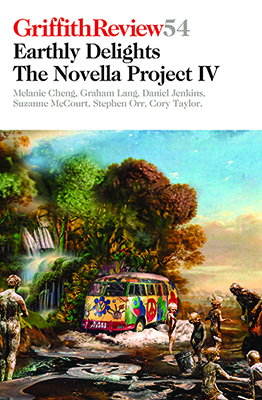

THIS YEAR’S NOVELLA collection will take you into five very different worlds, populated by a diverse range of characters – some who may find a place to live on in your mind. I am grateful to the Copyright Agency Limited’s Cultural Fund for again supporting this edition, to the 177 writers who entered, to the hard-working Griffith Review team who read them all, and to the distinguished judges, Sally Breen, Nick Earls and Aviva Tuffield, who had the difficult task of selecting the best of the bunch.

In addition, we hope you enjoy the beginning of the novel Cory Taylor was writing before her life reached its untimely end. Cory wrote regularly and beautifully for Griffith Review – her ability to evoke character, place and story in her writing was exceptional, and her generosity to other writers and readers knew no bounds. In her final months she wrote a profound book, Dying: A Memoir (Text, 2016), which meant that her third novel remains a work in progress, one to take root in your mind, allowing you to imagine how it might develop. A gift from a treasured writer to her readers.

Share article

More from author

Move very fast and break many things

EssayWHEN FACEBOOK TURNED ten in 2014, Mark Zuckerberg, the founder and nerdish face of the social network, announced that its motto would cease to...

More from this edition

A fulcrum of infinities

FictionSAUL TURNS OFF the bitumen onto the dirt road and drives due west. The ute rattles along over the corrugated track; its tyres rumble...

Muse

Fiction I’VE NEGLECTED HER. Her ceilings are soft with cobwebs. Her garden is choked with weeds. Her fence leans, like buckteeth, out onto the footpath. She...

The last taboo: A love story

FictionHE INSISTS ON a hotel room. You want him to stay with your family – you, Graeme and daughters, Sal and Janie. I want you...