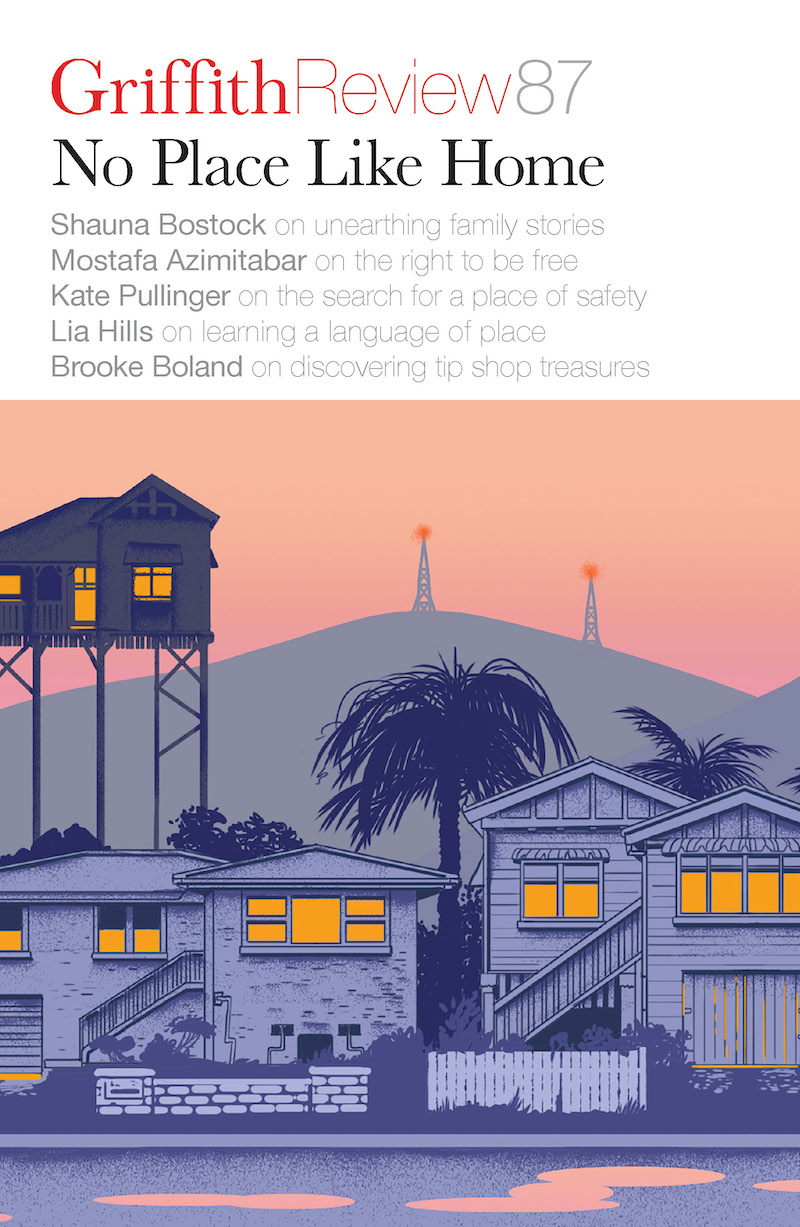

Featured in

- Published 20250204

- ISBN: 978-1-923213-04-3

- Extent: 196 pp

- Paperback, ebook. PDF

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

About the author

Tony Matthews

Tony Matthews is an urban planner, scholar and international advocate for good cities. His award-winning work addresses current and emerging urban challenges through research,...

More from this edition

More than maternity

Non-fictionPrinciple among art-history instances of breastfeeding are paintings, sculptures, tapestries and stained-glass art in churches that relay key Biblical moments of the Virgin Mary nursing the baby Jesus. Should you find yourself in the corridors of the Louvre, in the same halls where kings and princes are eternalised, one singular image of breastfeeding will make its way towards you time and time again: that of the Virgin Mary nursing the baby Jesus, which emerged in the twelfth century and proliferated in full bloom from the fourteenth as her cult of worship grew. In art, the nursing Virgin is called the Madonna Lactans, and she is a sanctity. Most of all, as the Church’s model of maternity, she is silent.

Follow the road to the yellow house

Non-fictionI first visited Varuna in 1994. I had just left my job as the Aboriginal Curator at the Australian National Maritime Museum, where I was involved in establishing the first gallery dedicated to addressing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander maritime history. I remember that visit well – even then I felt at home. I grew up in the Blue Mountains. My parents bought our family home there in the early 1970s. It was built in the 1940s, which means that it has a similar interior to Varuna, with ornate cornices, creamy white bathroom tiles, a green basin and bath, Bakelite door handles and even an old black phone.

Songs of the underclasses

Non-fictionDiē was the best driver I knew. ‘When you drive, you stare at everything but see nothing. You’re inexperienced,’ he lectured. ‘When I drive, I stare at nothing – I can chat, I can sing. But I see everything. Parking spaces, jaywalkers with a death wish, doggies and kitties. And for hours at time, without breaking concentration. It’s like meditation.’ Diē’s love language included showing me footage of near-miss traffic incidents on WeChat. Each trip of ours decreased my risk of appearing in his feed. These hours became the most time we had ever spent together.