Featured in

- Published 20230502

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-83-2

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

CLAY PIPE. TOFFEE Fingers. Blind Date. Light Rice. I am standing in the paint aisle of Bunnings. George sent me to pick out colour swatches for him to look over. He said he is interested in whites and greys, but that he trusts my judgement – I am the artist after all. According to my Architectural Digest subscription, greys are out and shades of brown are timeless, so I decide to go with Dulux and select ten options. George is an old friend of my sister and is paying me $150 a day to paint the interior of his house. I’ve never painted a house before and don’t know award rates, but he is doing my sister a favour. He is chronically ill and mysteriously wealthy. Wealthy enough to have paid a professional. We both have taste and I think that’s why we get along. I also get free board in the sunroom and the house is air conditioned, so it seems like a good deal, all things considered.

Back at the house, George is napping in the lounge. I arrange the swatches before him on the coffee table and go to make peppermint tea. As the kettle boils, I hear George stirring and get another cup from the cupboard. I’ve been here less than a week, but feel more at home already than at the house I shared with Susy on the other side of the river. There’s a familial quality to our relationship that I find comforting. Most mornings I sleep in and wake at midday to find George ploughing his way through Russian novels or gabbing to his interstate friends over FaceTime. In the afternoons I join him on his daily constitutional to the river. He takes a route that meanders along the Woolstores, stopping regularly to catch his breath or admire a bird or flower, something small but striking. Sometimes I take a sketch pad and churn out quick portraits of George as he smokes a single cigarette, looking out over the water to the peak-hour ferries. He is the most elegant man I’ve ever met and praises my scribbles as though I am a small, precocious child. At night, we watch Home and Away together, and in the ad breaks he relays gossip from his guest stint in the ’90s. I enjoy George’s company, but am eager to get to work, to give my days direction and purpose. I expect the tedium to be exhausting but meditative. I need to centre the furniture first, wash the walls with sugar soap, acquire drop sheets and masking tape. This is what Google tells me to do.

It was convenient that things with George aligned when they did. We’d always been cordial, Susy and me, but there was never any warmth or camaraderie between us. Mostly we kept out of each other’s way, which was easy as I was out most evenings or teaching late classes during semester. We only overlapped at breakfast, when she would complain about how I woke her up the night before, yet again, with my aggressive footsteps. I honestly wonder if you do it on purpose, she once said as she did her make-up in the kitchen where the light was most flattering. It’s so fucking loud. Can’t you at least take off your shoes?

If I told her I always, always take my shoes off at the door because I am a civilised person, I knew she wouldn’t believe me.

I poured myself a cup of coffee and watched as she worked some sort of pomade into her eyebrows, looked away right before I knew it would start to irritate her. She began complaining about her boss, who flossed his teeth at his desk and refused to give her a raise. I listened and laughed when prompted. She could be funny at times, I’ll give her that. When she left for work I rifled through her lime-green neoprene bag, picked out the pot of pomade and combed the spoolie through my eyebrows. My first class of the day didn’t start for a few more hours, so I had the morning in front of me. I did my whole face, and when I arrived at the tutorial room I knew the students could tell there was something unusual about me, but couldn’t place what. This happened a few times. Susy and I would have the same conversation about my obnoxious footsteps and in return I made sure never to point out her bad qualities, not even once, not even when she found the eyeball in the fridge and told me I needed to move out.

GEORGE IS TAKING a long time to settle on a colour scheme. It’s a big commitment, so I try not to pressure him. He lands on Clay Pipe then changes his mind to Light Rice, Camel Hide for trim. We decide to wait until he’s sure before I return to Bunnings to buy the paint. We continue with our routine, but one afternoon he suggests that, instead of our usual walk, we head out for an aperitif before dinner. I assume we’ll take his car, but he makes no move to retrieve the keys to the zippy Prius he keeps parked in the garage, so I follow him to the street and unlock my Corolla. It’s been ages since someone else has been in my car, and I try to inhabit it as though I were a stranger. It is clean. No noticeable odour. I am conscious of George’s position in front of the glove box, but grateful for his usual good manners, his hands tucked neatly into his lap. He isn’t a mindless fiddler and, unlike me, is respectful of boundaries.

We sit at the bar and order. It’s been a while since I’ve been out, and I keep tugging at my skirt to cover my thighs. George seems to know the bartender, and as they chat I excuse myself to go to the bathroom. The lights are dim and I lean against the wall and wait for a stall to become free. Two women are having a loud conversation through the cubicles. I try to listen but they are talking in an intimate shorthand and none of it makes sense. They sound happy and confident, just a bit drunk. A toilet flushes and one of the women emerges from a cubicle. She is wearing a neon-pink suit, peroxide hair, lots of gold jewellery. Given the clipped sound of her voice and the demographic of the other patrons at the bar I expected her to be middle-aged, but she is younger than me, probably. She startles when she sees me, which I find confusing seeing that my footsteps are so offensive. I fight the impulse to apologise and slip into the stall, my underwear already around my knees by the time I notice the phone on the cistern. I call out to tell her to wait, but there is a loud cackling before the bathroom door thuds shut.

After I wipe and rearrange my skirt, I reach for the phone. It fumbles from my hands, smashes onto the concrete floor. There is a painful crack sharp across the black screen. I pick it up and press the power button. Her wallpaper is of a small dog that resembles a ball of caramel wool, and the crack runs down the centre, cleaving its dopey face in two. I feel bad for a moment, before realising the woman doesn’t have a screen protector and can only blame herself. As I exit the bathroom, I imagine the conversation I am about to have with her. I will adopt a matronly tone, tell her to take more care with her belongings and hope she doesn’t see the cracked screen – but if she does, I will remind her to be thankful it didn’t land in the toilet water, be grateful I didn’t steal it, but when I scan the room there is no sign of pink. The bar is on the ground floor of a hotel, and I look up, as though I can see through the ceiling to where she has gone.

Having finished his martini, George asks what took me so long. I tell him there was a queue, and he pushes my drink towards me. I wonder whether people think we are father and daughter and hope that they do. When I finish my drink, I dislodge the olive from the toothpick with my teeth. It feels slimy, rolling against my gums, and I gag on the texture, spit it unchewed into my napkin. George is back to chatting with the bartender and hasn’t seen me be uncouth. It takes me a while to figure out that George is flirting, and I have the idea to tease him about this later, before realising we don’t have that kind of relationship yet.

It isn’t until we return home from the cocktail bar that I finally relax. I tell George I’ll be inside in a minute, and as he makes his way to the gate I unbuckle my seatbelt and reach across to the glove box. Of course, it is empty, but I still feel disturbed as I peer into the black well. When I exit the car and turn to the house, I am relieved to see George waiting for me at the front door. It’s dark now but the air is still warm and fragrant: cut grass, jasmine. Once I am inside, George locks the door behind me. I am sure he has read my mind and I have never felt safer.

BEFORE BED, I log into my old email address. It’s mostly spam and discount codes. I skim over each sender and subject line for anything nefarious, but nothing grabs my attention. At the beginning, when he first made contact, I assumed it was a joke: an ex-lover seeking petty revenge for being discarded, or a student I’d failed trying to get back at me for their own lazy incompetence. My work address was easy enough to find, but he soon discovered my personal email from my lo-fi artist website where I sold my astrology collages and commissioned portraits of people’s dead pets. After the initial messages came the photos, the videos. On Valentine’s Day he sent me a picture of himself holding a carnation and a homemade card, smiling coyly at the camera. He had the handwriting of a twelve-year-old boy, the size of the printed lettering inconsistent and swooping downwards the farther he got from the margin. He filmed himself covering INXS songs on an acoustic guitar and told me if you don’t have a rape fantasy you will reply to this email, you cold bitch.

Once I showed a Tinder date a selection of screenshots, and as he kissed me goodbye at his front door, he wedged the knife he kept in his boot into the back pocket of my jeans, so smoothly it could have been a well-oiled move. It was dirty gold and shaped like a fish. In the Uber home I practised flicking the knife open and closed between my knees so the driver didn’t panic or give me a bad rating.

I carried that knife with me everywhere, clipped onto the waistband of my pants, the metal cold against my hip, but when the time came to use it, I forgot it was there. For days afterwards, I waited for the police to turn up on the doorstop. I kept refreshing the local news, typed variations of ‘assault’ and ‘eye-gouge’ and ‘Brisbane’ into Google. The most recent result was from the previous April: a glassing incident on a man in his sixties in a Spring Hill pub that had nothing to do with me. It was November; I didn’t return to campus for months, didn’t have any real need to leave the house at all. I was still waiting for my first batch of marking to come through, and the days stretched out, facilitating my listlessness and the small nugget of suspense that was beginning to form inside me. I printed the emails and Facebook messages – hundreds of them he sent me, on and off for years – and re-read them in order like a well-thumbed book, one I knew very well.

I’d graduated to skimming transcripts on the Supreme Court website when Susy found the eyeball. There was a feral screech and a minute later she was standing in the doorway to my bedroom. What is that thing in the fridge? When I played dumb, she said in the blue Tupperware. What the actual fuck?

I felt vindicated at first. For months I’d known she was prowling through my stuff, stealing my food. I was a good cook and shopped at boutique delicatessens. Financial literacy podcasts hosted by peppy millennials constantly preached from Susy’s phone and, as a result, all of her food was Home Brand and cooked in bulk.

I told her it was just something new I’d been working on, and gestured to the sketches piled up on the desk. I tried to sound flippant and occupied. It must have worked – at first, at least – because she sighed and left me in peace, though I felt uneasy and knew a decision had to be made. When I heard the Netflix intro boom through her laptop, I crept into the kitchen and took the container from the fridge. I thought about tossing it in with the vegetable scraps, before remembering that meat products are not compostable. I opened the rubbish bin and tipped out the container. I tried not to look at it, but it was hard to resist. The eyeball gazed up at me. The iris was pale brown, the deep red tendrils of tendons limp and shrivelled. Of course his eyes were the colour of a pasty, deficient shit. I did that, I thought. I did that.

THE NEXT MORNING my car is gone. I walk out to the street in my pyjamas and stand where I parked it when we arrived home from the bar. An off-leash cavoodle ambles by and sniffs at my bare feet. I lean down to pat it, but it loses interest in me and trots off down the path, trailed by its owner who appears from nowhere. She looks like the woman from the bathroom, a stripped-back, neon-free version, and for a moment I am scared she has somehow tracked me here. I try to remember what I did with the phone, but there are spots in my mind and I can’t recall. When I smile at her, try to look inconspicuous, she ignores me and continues after the dog. I turn back to the gutter and wonder if I parked somewhere different; maybe the martini was stronger than I thought. I walk up and down the street but the car is gone.

After breakfast, I check my work email. There is a message from a professor offering me my usual teaching for first semester. I start to type a reply, then delete it. Type. Delete. I have the realisation that teaching was another life, something I cannot return to, even if I wanted to, and then I delete the email.

A WEEK LATER, George hands me an envelope with $500 in it. I am confused because I have not started painting yet. I try to return it, but he says it’s an advance. I feel simultaneously guilty, because I am taking advantage of his kindness, and pathetic, because I know he pities me. I don’t mind being pitied, so I go to the bank and deposit the majority of the cash into my account. With a good chunk of the money I buy George a pair of velvet smoking slippers. They are navy with a sailor’s knot stitched in gold on the front toe. When they arrive in the post, I make sure I am the one to answer the door. I think about wrapping them, before deciding to leave them on his pillow. After seeing how good George looks in them, I buy myself a pair with the colours inverted, and together we swan around the house in our matching slippers, like a set of stylish geriatrics. I fantasise about matching jackets to complete the look.

I am trying to get closer to George. After a few weeks, I realise we never talk about anything personal. The conversation is always buoyant and easy, about art or literature or what we read that day in the news. I’m not sure what my sister has told him about me, but I get the sense he thinks I’m fragile, that if he probes too deep it will unlock something chaotic and strange. I’m beginning to worry that my sister has pressured George into having me, or that she herself is paying me to do the painting. I wouldn’t be surprised; it’s something she would do. Whenever I mention my sister, George reminds me that she’s been trying to get in touch with me. I’ve been screening her calls and tell him I’ll call her back. She doesn’t know about the eyeball. No one does, except for Susy. It’s not like we are close, my sister and I. She’d just turned eighteen when I was born, already out of home. She works in Melbourne as an accountant, that’s how she knows George. She was his accountant. People are always surprised to hear that I have a sister. They are more surprised to hear she is an accountant seeing as I am so bad with money. What they don’t seem to realise is that it’s because she literally studied money.

I am at George’s when she sends me a bouquet of flowers for my birthday. We communicate through floral arrangements. When I finished my PhD, she sent me a potted peace lily instead of the usual bouquet and I was hit with an inexplicable sadness. I place the flowers in a pink resin vase and position it by the window in the sunroom. I take a photo and post it to Instagram and wait for the likes to improve my mood.

On our afternoon walk I ask George for one of his cigarettes and when he says no, it confirms my suspicion that he doesn’t see me as a real person. Don’t sulk, he says. I try to arrange my face into a neutral, pleasant expression, but am embarrassed that I’m a thirty-year-old woman behaving like a toddler. I’m embarrassed that I don’t have a proper job or any savings, that I board with a man who is likely being bribed by my sister to put up with me. Earlier a friend messaged, asking me to dinner, a belated birthday celebration. I’d planned on ignoring her, but decide to go so that George can have some time alone. I make an effort with my appearance and call an Uber from outside. George hasn’t seemed to notice that my car is missing. I know I need to file a police report, but at the thought a sensation of damp suffocation comes over me. It’s not like I need a car, really. I decide to cut my losses as the driver pulls into the gutter.

Of course, Susy is at the restaurant. Bea and I are seated at the back, shrouded by artificial palm leaves, and I claim the chair that gives me the best view of Susy and her date. She doesn’t notice me for a while, but I clock the instant she does, because her posture stiffens and her laugh becomes performative. When Bea goes to buy another bottle of wine from across the road, I watch Susy eat a spring roll, spoon rice onto her plate. She’s wearing a new polyester jumpsuit and has lightened her hair. I saw on Instagram she just bought a unit, and I think about approaching her table to offer my congratulations. I’m happy for her, I really am. I’m glad the years of restriction and discipline paid off. The man she is with glances over his shoulder, right in my direction, not subtle at all, which suggests they’ve started talking about me. I wonder if I’ve become an anecdote: the housemate from hell. I wonder if she tells people about the eyeball in the fridge and whether she embellishes the story, goes on and on about what a freak I was to live with, how relieved she is that her share house days are behind her.

I’m still deciding whether or not to leave her in peace when Bea returns. Pouring rosé, she asks me which days I’ll be on campus this semester. We sometimes teach the same units, except Bea has a full-time lecturing position and is very good at her job. I tell her I’m not going back to teaching, that I want to try something different. I tell her about my arrangement with George, and that it might turn into a long-term thing. Like a sugar baby? she asks, and when I tell her no, not like a sugar baby, she seems confused still but doesn’t push it. She asks me about the stalker, and I tell her I haven’t heard from him in a while, that he’s probably realised I’m not worth the effort and moved on to terrorising someone else.

As Bea finishes the wine, I take care of the bill at the counter. I ate too much Penang curry and feel sick. They won’t accept the last of George’s cash for hygiene reasons, and it takes me ages to transfer money into my account on my phone because I don’t know my online banking password. Bea is outside by the time I sort it, and as I pass Susy’s table on the way out, an impulse overwhelms me and I lean down and call her a cunt, quietly, practically a whisper so that she is the only one who can hear it, not even her date who, up close, is handsome in a benign, silky way, like a castrated seal. I don’t know why I’m being like this. She hasn’t done anything wrong. I don’t even think she is a cunt, not at all. In the Uber, I text her an apology, but she doesn’t text back. When I search for her Instagram, I see that she’s blocked me. I’m glad I’d had the foresight to take screenshots of her brand-new, third-storey unit, which I scroll through until the car pulls into the driveway.

GEORGE IS ASLEEP on the lounge. I cover his body with a blanket, switch off the TV and all the lights he’s left on. I’m not tired, but don’t want to disturb George, so I put on my slippers and sit on the lounge chair across from him. I feel the onset of a headache, a sharp excavating at the back of my skull. There is a slimy feeling in my guts, comparable to homesickness, which sometimes comes on when I drink too much and dwell on the mechanics of the eyeball. The eyeball. I should probably tell George, I realise, about the eyeball. I don’t know why I haven’t thought about it before. I want to do it this instant, to shake him awake, but I decide it’s best to wait until morning, when I am fresh and well-rested. I have a feeling he will understand. He will probably tell me he’s done the same thing. There would have been all kinds of deranged people after him for those years he was on Channel 7. He’s better looking than me and far more charismatic. I bet he has a whole collection of eyeballs hidden away somewhere, like trophies, and I bet he will show me those trophies and ask me to stay with him for good.

THAT NIGHT, I dream bad dreams about Susy’s seal companion and what I will tell George: about the body staggering out of the campus carpark in my rear-view mirror as I locked my doors and drove away; the feeling of it, warm, like a just-boiled egg, slippery when I opened my fingers to observe it on my palm; how I placed the eyeball in the glovebox and went to bed, that I slept soundly and for the first time in a long time was without worry or fear. I will tell him I didn’t know I had it in me, that kind of violence.

When I wake, I am upright, a crick in my neck, my mouth sour, pungent. I hoped George would be beside me so we could joke about our stiff, frail bodies and how we’re not getting any younger, but the blanket is folded at the end of the lounge. I look in all the usual spots for him: the kitchen, the back patio. Upstairs, I tentatively enter his room to hover by the en suite, but there is no sign of life on the other side of the door.

I am about to go down to the garage to see if he’s taken his car, but when I get to the hallway I am startled by the front door and the fact that it is wide open. I step through it and try to remain calm as I call George from the front yard. It goes to voicemail, so I text him, call him again. On my third attempt my hands start to prickle, my thighs and crotch rubbery and numb and cold. I realise I’ve wet myself but shame doesn’t come. During the night it rained, and I concentrate on the verdant grass, the footpath dark grey. I am usually asleep at this time of day and am dazed to see the street so busy and full of life: the chugging council bus, the distant clang of a school bell, the heinous orange scooters intimidating pedestrians out of their path. I watch sweat-drenched runners and mothers with prams, suits charging to the ferry terminal. A pair of school kids begin to grope each other right in front of me, so close that if I stretched out my hand I could touch the girl’s shiny ponytail, the boy’s muscular rugby wrist, but I am hidden by the wisteria snaking the garden arch. They cannot see me watching them; they cannot watch me back.

When George returns, he is holding a tray of coffee cups in one hand, a brown paper bag in the other. I got us breakfast, he says, and passes me the bag, which holds two warm butter croissants. George strolls up to the front door, disappears inside, but when I try to follow him, something in my body collapses my knees and I find myself on the grass. It’s not so bad down here, under the shining sky, the clear sun, the loud of the street. Across the road, a block of units is in the final stage of development, and I think of Susy beaming in front of a ‘sold’ sign with freshly popped champagne cascading down her wrist, and Susy posing seductively on her balcony in cut-offs, a set of fiddle-leaf figs phallic at her feet, and Susy standing at her front door holding a welcome mat, mouth wide, gesturing tackily to the brown slab of turf, brass number seven lucky on the front door, and the camera positioned above the left-hand corner, the screen smooth and domed as a contact lens and the red light frozen in demonic scrutiny, looking at me, looking at me, looking.

This piece is one of five winners of the 2022 Griffith Review Emerging Voices competition, supported by the Copyright Agency Cultural Fund.

Image credit: Getty Images

Share article

About the author

Emily O’Grady

Emily O’Grady’s first novel, The Yellow House, won the 2018 The Australian/Vogel’s Award, and in 2019 she was awarded a Queensland Writers Fellowship. Her...

More from this edition

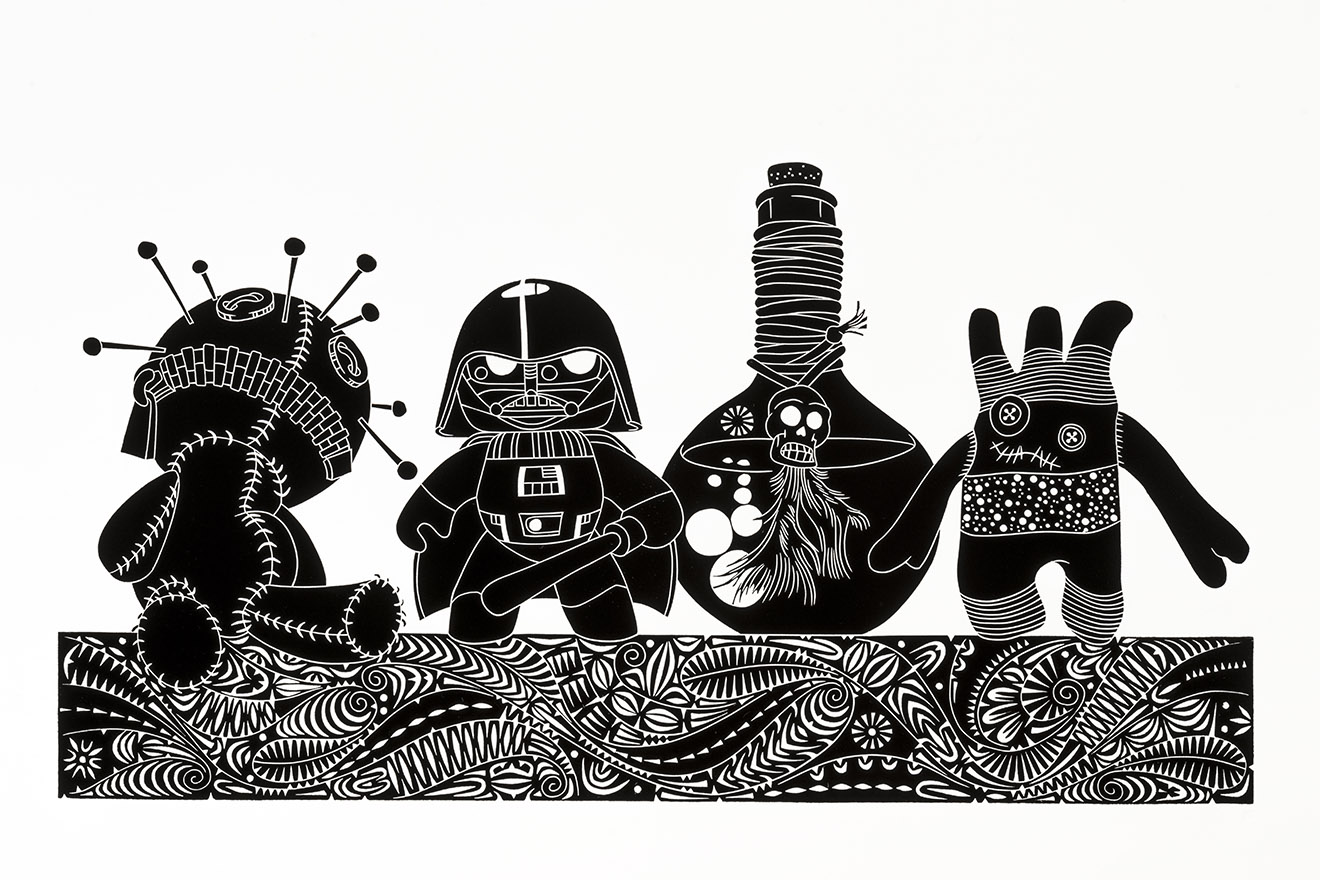

Pop mythology

In ConversationEven though I grew up on a small, remote island, I was still heavily influenced by television – particularly the sort of cartoons that would play on Saturday mornings, mornings before school, after school and so on. When it comes to DC and Marvel and all of those superheroes, for me that was ignited by my late grandfather Ali Drummond, my mother’s father, who had boxes of Phantom comics. Phantom was my early introduction to the strong, powerful male being who had supernatural strength and abilities.

Have you ever seen the rain?

FictionOne by one the streets quietened down. A great hush washed over this city. Even the lights at night seemed dimmer. All of life lay dormant. Or maybe not – Toru couldn’t trust his eyes, could he? He had been living on the streets in the clothes he died in, scrounging food from tables outside restaurants and cafés around the city, but those tables were long gone.

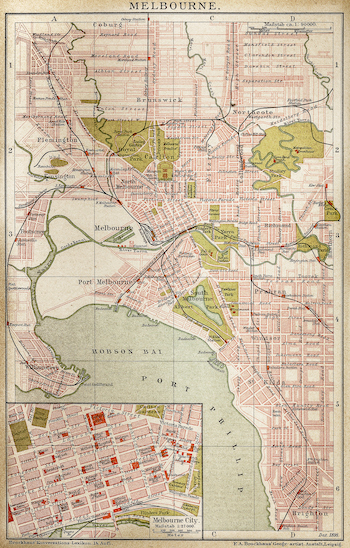

The dancing ground

Non-fictionAfter some initial research, and only finding one historical reference to a ceremonial ground within the CBD, I confined the puzzle of Russell’s lacuna to the back of my mind. The single reference I found was in Bill Gammage’s book The Biggest Estate on Earth, where he writes: ‘A dance ground lay in or near dense forest east of Swanston Street and south of Bourke Street.’ Not a great lead because it was two blocks away from where it was depicted on Robert Russell’s survey.