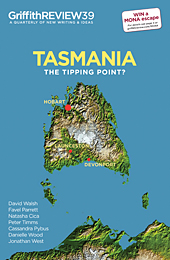

Featured in

- Published 20130305

- ISBN: 9781922079961

- Extent: 264 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

A life in books

Memoir NOVEMBER 1952: BERNARD Marks has just arrived in northern Egypt from Salford, in the north of England, to begin two years of National Service...

More from this edition

Damming

FictionPATRICK SWIMS THROUGH the mountains. The eddies waver them. They're the colour of oil slick. The light blushes his cheeks. He's swimming breaststroke. It's...

Churning the mud

EssayPREJUDICE, IGNORANCE AND shallowness characterise the current national debate on Tasmania and its future. On the political right the island is portrayed as the...

The science laboratory

ReportageTHE CAPTAIN STEERING Australia's Antarctic science program into its second century can't risk getting caught in the wake of history as he casts off...