Featured in

- Published 20241105

- ISBN: 978-1-923213-01-2

- Extent: 196 pp

- Paperback, ebook, PDF

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

About the author

Amy Carkeek

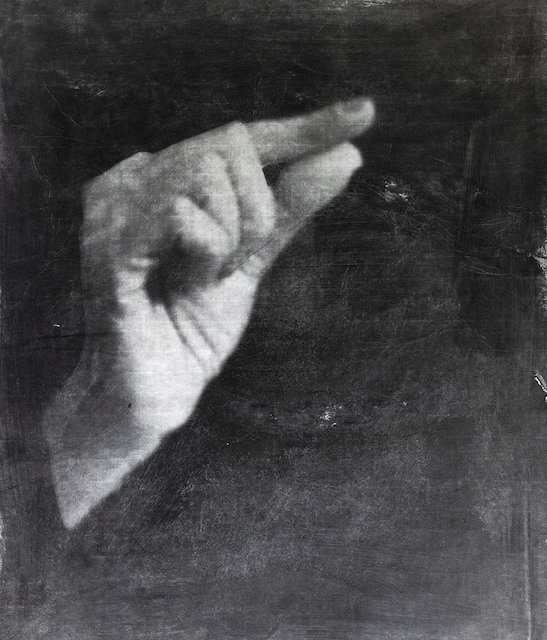

Amy Carkeek is an Australian artist and researcher. She has exhibited in galleries across Australia and the US, and has been a finalist in...

More from this edition

The power of a curse

Non-fiction IT WAS JANUARY 1995 when my father showed me how to lay a Gypsy curse. I had just published my first novel, Crazy Paving, and...

The window

FictionOne dinner, in the midst of playing with Seb in the reflection, Rudi laughing and squealing away, there came the distinct burst of a sob. We stopped in our tracks, looking around at each other in confusion until we located the downturned whimpering in Tim’s eyes and mouth. What is it? I asked, putting my hand on his shoulder. He turned and buried his face into my neck. What is it? I repeated. I don’t like them, he moaned, his hand pointing towards the window.

upstart crowe

Poetry I was reading Shakespeare on my phone & then this rose started blooming in front of me as if embarrassed I’m calling collect –...