Featured in

- Published 20230207

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-80-1

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

About the author

Martine Kropkowski

Martine Kropkowski is a writer and HDR candidate at The University of Queensland. Her research examines folklore practice in the online space, including the...

More from this edition

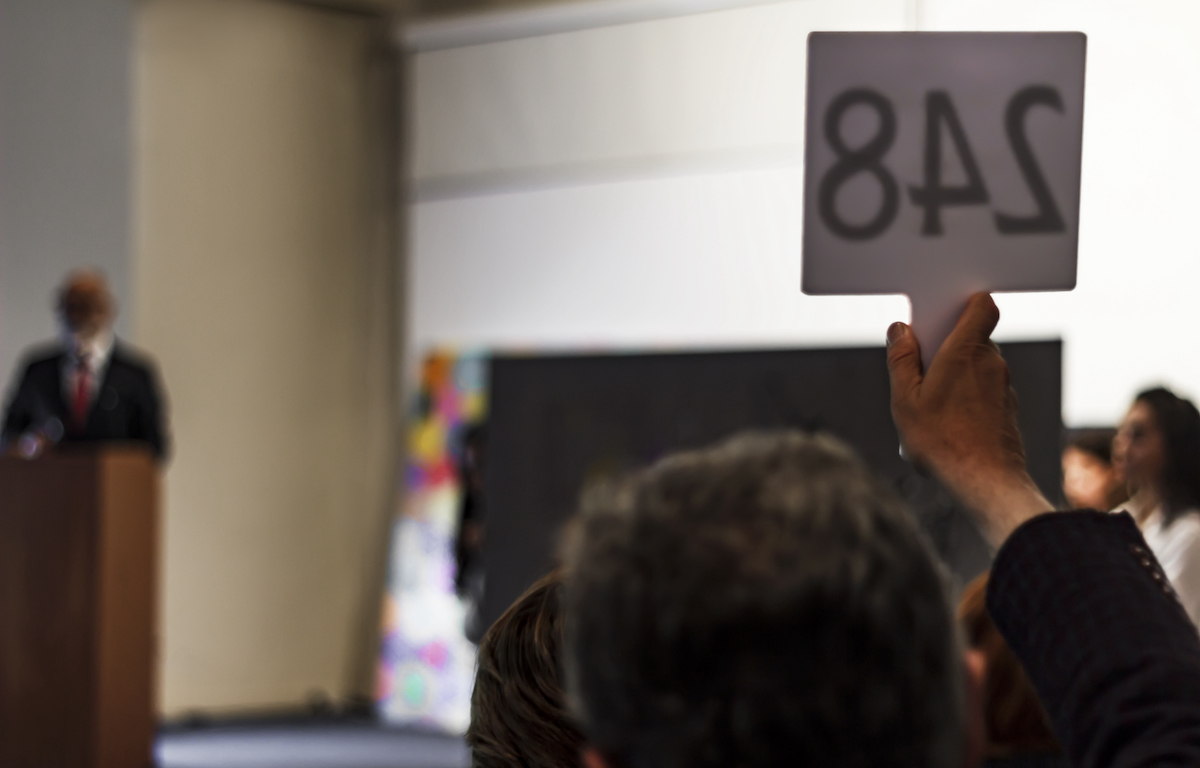

The future of art fraud

Non-fictionOver lunch with the international art auctioneer, I told him the art dealer – a mutual acquaintance – said she would ‘support’ my work at auction. She explained that if an artwork didn’t receive enough bids during an auction, she would bid to buy it for a higher amount. Then there would be a public record of my work being sold for the value assigned by her, which she would show people when reselling it privately.

Will we dance when it’s over?

Non-fictionThe stakes in our real world have reached a point so high, so close to apocalypse, that they’ve disappeared entirely. We are gripped by a nihilism and unnerving sense of unreality, and so we don’t receive the messages others are trying to send to us.

Self-portrait in Joy Hester pocket mirror

Poetry All hail my inner bones, things have been troped yet now heat up. Being Bowie gone to Berlin, genuinely out of ideas and summoning Brian Eno wearing...