Featured in

- Published 20240206

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-92-4

- Extent: 204pp

- Paperback, ePub, PDF, Kindle compatible

IT’S HARDLY A new observation to say that everything old is new again. Nostalgia in the twenty-first century is not so much a feeling as a cultural force: TV shows and movies are now frequently set in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, offering exaggerated re-creations of the aesthetics that defined those eras (did my parents’ 1980s suburban living room look anywhere near as stylised as those that appear in Stranger Things or Physical?); Instagram accounts churn out memes and anecdotes that epitomise the decades in which their millennial audiences came of age; and, perhaps most confronting of all, my eighteen-year-old niece dresses exactly like the cool kids at my high school did a little more than twenty years ago.

These examples might sound trivial, but I suspect they’re just symptoms of a wider malaise. For New York Times critic Jason Farago, we’re living in ‘the least innovative, least transformative, least pioneering century for culture since the invention of the printing press’. He’s not saying we’re incapable of producing great art, or that creativity is flatlining – if anything, we’re generating more content now than ever before. And perhaps that’s the problem: when technology can deliver us whatever song or story or sartorial look we desire, time loses its meaning.

Funnily enough, Farago’s view isn’t new, either: ten years ago, the late, great cultural theorist Mark Fisher (who makes a couple of cameos in this edition) posited that our ‘montaging of earlier eras’ had reached such fever pitch that we no longer even noticed our submersion in a sea of bygones. And sitting alongside this purported cultural inertia are our increasingly divergent attitudes towards history – the far-right impulse to romanticise the past, the far-left desire to remedy its wrongs – and how they inflect our politics.

If we’re truly stuck – caught between competing strategies to achieve progress as we recycle and remix what’s come before – what does this mean for our future?

PAST PERFECT HOLDS this complex prism of the past up to the light. Its essays, fiction, conversations and poems refract myriad perspectives, contexts and approaches. In this collection, you’ll discover how technology mediates our memories; revisit the heady world of last century’s ad industry, with its questionable gender politics and wild parties; reconsider national narratives and the ways in which literature, particularly by First Nations writers, can challenge them; understand the complex relationship between our words and our worldview; take a tour through the decadent creations of leading Australian artist Michael Zavros, whose work resists moral interpretation; examine the joy of loving lowbrow culture; explore the evolving legacy of Scarlett O’Hara, a character who’s been revered and reviled for nearly a century; consider how nostalgia can be weaponised in pursuit of flawed political ideals; and much, much more.

I’d like to thank the Copyright Agency Cultural Fund for their ongoing support of our Emerging Voices competition – we’re very proud to publish work by the first of our four talented 2023 winners, Beau Windon, in these pages.

It’s probably fitting that this edition, with its double vision of past and future, is the first of the year – a year that will, no doubt, yield yet more technological innovation and political polarity alongside a fresh tranche of cultural and artistic reboots and callbacks. I hope this collection can offer you new ways of thinking through them all.

3 January 2024

Image credit: Getty Images

Share article

More from author

Subject, object

The vivid hues and spiky leaves of Jason Moad’s Temple of Venus – the arresting artwork featured on the cover of Griffith Review 89: Here Be Monsters – raises a tantalisingly sinister proposition. The subject of the painting is clear – a Venus flytrap, realistically rendered – but there’s a somewhat otherworldly quality to this plant, a sense that it might be biding its time, waiting to strike while we, the viewers, are distracted by its beauty. For Melbourne-based realist painter Jason Moad, this slippage between subject and object, reality and imagination, is part of the point.

More from this edition

Lines of beauty

In ConversationI studied printmaking because in the mid-’90s there wasn’t so much exciting painting happening in QCA studios, but also because I really wanted to learn new processes for my undergrad and, like most artists, I’d always painted. Painting had fallen out of fashion, and everyone was making installation, then photography and film – the new digital world reigned supreme for a decade. Now it’s all about painting.

Anticipating enchantment

Non-fictionWhen an editor works on a book, they balance reader expectations with what they interpret the author’s intentions to be and use their experience to make suggestions. This might mean changing some of the language to ensure the work is comprehensible for general readers, or asking for more detail where a setting has been hastily described. An editor will always be anticipating the market, and their extensive reading of contemporary works makes them well-placed not only to understand the social and political conditions of the day but also trends in publishing and marketing.

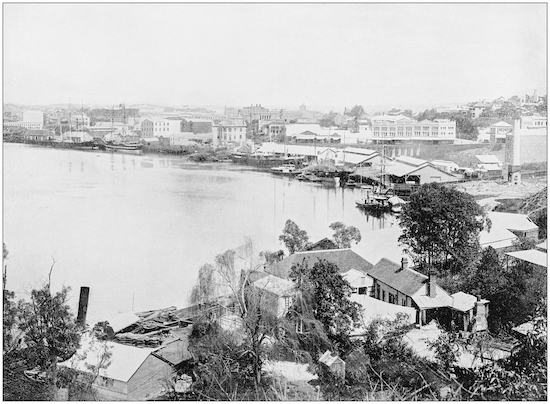

Always was, always will be

In ConversationIf Aboriginal people are all dead, you don’t have to negotiate a treaty with us and you certainly don’t have to go around feeling guilty about stolen land and stolen wages and stolen children; the subjects of that injustice don’t exist anymore if you choose to believe that we’re dead or all assimilated, which isn’t the case. It’s a very practical kind of assimilation strategy.